【Text by Observer Net Columnist Chen Feng】

For a period of time, people have had enough psychological and material preparation for the U.S.-China relationship entering deep waters, but there has been no corresponding preparation for the Sino-European relationship. In the Biden era, it is easy to imagine the convergence of the U.S. and Europe, but in the Trump era, the U.S.-European relations were tense. Shouldn't Europe have moved closer to China? However, this did not happen.

After her visit to China, von der Leyen immediately signed a trade agreement with Trump, agreeing to impose a 15% tariff on goods exported to the U.S., increasing investments in the U.S. by $60 billion, purchasing U.S. military equipment, and buying U.S. energy products worth $75 billion.

This clearly reminds China that the illusion of Europe can be shattered.

On July 24, EU President von der Leyen, European Council President Costa, and EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Kallas attended the 25th China-EU Summit in Beijing. REUTERS

"The New Tripartite Era": What's Happening with Sino-European Relations?

The President of the European Council (roughly equivalent to the EU "head of state") Costa is a rubber stamp, while the President of the European Commission (roughly equivalent to the EU "head of government") von der Leyen, EU Commissioner for Foreign Affairs Karas, and EU Commissioner for Trade Shevchenko are pro-American, but the major direction of the EU is not solely decided by a few individuals. These individuals were elected through competition and interest balance within the EU, and they should represent the interests of the EU.

The United States, the EU, and China are the three most important political, economic, and cultural forces in the world today. Britain, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand are aligned with the U.S. and Europe, while India and Russia are all categorized as "others."

People often compare the U.S.-China-EU relationship to the Three Kingdoms, which makes sense, but whether it aligns with the perspectives of the three sides depends on the viewpoint. In the Three Kingdoms, the northern Wei was the strongest and most aggressive; the eastern Wu was second in strength, but still weaker than Wei, and also had its own ambitions against the western Shu; the western Shu was the weakest, but due to the greatest survival pressure, it lived the most cleverly and vividly.

In the Three Kingdoms, Shu was beloved because of Zhuge Liang and the Five Tiger Generals, while Cao Cao and his army were symbols of evil, and Sun Quan and Zhou Yu were seen as petty people who neglected great righteousness for small gains. This is a stereotype from literary works, but reality is more complex and dry. In the U.S.-China-EU context, who is the魏 (Wei), 蜀 (Shu), and 吴 (Wu)?

From the Chinese perspective, China is the weakest Shu, and being smart and capable is just a byproduct of the literary comparison, but it also fits the Chinese self-perception. The U.S. is undoubtedly the Wei, powerful and bullying. Europe is the Wu, fawning and forgetting loyalty for profit.

From the American perspective, power and situation are separated. The U.S. is the most powerful, but in terms of situation, it is being pressured by the Wei and having its ground taken by the Shu. China, in terms of power, is only the second Wu, but in terms of aggressiveness, it is comparable to the Wei. Europe, in terms of both power and situation, is the weak Shu, and even lacks the wisdom and capability of the Shu.

The European perspective is more complex. Europe is the starting point of modern industrial civilization and considers itself at the moral high ground of progressive values (such as environmental protection, human rights, sustainable development, multiculturalism, welfare policies, etc.). It holds a leveraged position in the Sino-U.S. competition, similar to the Shu. Due to the first-mover advantage accumulated since the Industrial Revolution, it has the power and strategic position comparable to the Wu. The U.S. has the power and strategic position of the Wei, but has the "friendliness" and "lureability" of the Wu. China has the aggressiveness of the Wei, the power of the Wu, and the strategic position of the Shu, after all, China is "on the wrong side of history."

Of course, China certainly does not see itself as aggressive, which is indeed an EU narrative. China's rise has substantially changed the geopolitical and economic reality, altered the course of history, and in a way, this is invading the existing world order dominated by the West. From the Western perspective, this is aggression.

In the current great competition between the U.S. and China, both sides are trying to win over Europe, and Europe sees this as an opportunity. The problem is, China wants to bring Europe to oppose the U.S., while the U.S. wants to bring Europe to oppose China, but what about Europe?

Europe used to think it could eat China and then eat the U.S., or eat the U.S. and then eat China, but suddenly found itself squeezed from both sides and struggling to survive in the middle. While China was unprepared for the sudden deepening of Sino-European relations, Europe was also unprepared for the sudden deepening of U.S.-European relations.

On July 27, U.S. President Trump held a meeting with EU President von der Leyen and announced that the U.S. and the EU had reached a new trade agreement. Visual China

Europe has long accepted the reality that the world center has shifted from Europe to the U.S., but Pax Americana and Pax Europa are compatible, not conflicting. Europe was earlier more luxurious than the U.S., and was even superior to China. But without realizing it, China suddenly grew into a room elephant. Europe thought "all roads lead to America," but reality quietly turned into "all roads pass through Beijing." During the pandemic, Europe suddenly realized how deeply and broadly it relied on the Chinese supply chain, and "de-risking" was simply unmanageable.

Europe is divided into "agricultural Europe" and "industrial Europe." "Agricultural Europe" cannot adequately support its manufacturing industry, or manufacturing is just for multinational companies, needing agriculture, tourism, and other sectors to sustain the national economy, along with subsidies from the EU (essentially Germany). Germany is the core of "industrial Europe," and relatively profitable manufacturing not only supports the German economy, but also serves as the basis for other EU countries to rely on Germany.

There are also countries between "agricultural Europe" and "industrial Europe," such as France, which has Airbus, Renault, and Total, but is also a major exporter of wine, perfume, cosmetics, cheese, and food. Netherlands has Philips and Shell, but is also a major exporter of dairy, flowers, and bulbs. The Netherlands' finance and services are also strong, with KPMG and ING.

The Chinese supply chain means consumer goods for agricultural Europe, which has relatively strong substitutability, while China as an export market has significant attractiveness. For industrial Europe, the Chinese supply chain is a double-edged sword, providing reliable sources of high-quality, low-cost intermediate goods, but also facing strong competition from high-quality, low-cost finished goods, making both difficult to replace. China's manufacturing is rapidly moving into high-end products, a comfort zone once firmly controlled by Europe, severely compressing Europe's competitiveness in exports to China, and price competition significantly affecting Europe's socio-economic cycle.

Europe practices welfare policies, improving the living standards of the lower class through wealth redistribution, enhancing social stability and happiness. Such a socio-economic model suppresses entrepreneurship and innovation, while relying on a few high-tax industries to support society. This is a "stop when you stop" socio-economic model, so Europe is particularly sensitive to "aggressiveness" involving the economic foundation.

When Europe was still at the forefront of technology and technological development was relatively slow, this system was not a big problem. But now, with rapid and even leapfrog technological development, Europe is falling behind, and the original system faces a risk of collapse. This is the anxiety currently faced by the EU.

On a larger scale, Europe's anxiety comes from economic dependence on the Chinese supply chain, technological dependence on the U.S. and facing strong pressure from China, security threats from Russia, and societal fragmentation. The abandonment by the U.S. and the rise of China have added extra anxiety. If the U.S. only causes confusion and injustice in Europe, China leads to deep doubts about Europe's "institutional superiority" and "cultural superiority."

However, Europe's response is fragmented. France seized the chance to revive "European autonomy," but its desire to lead is too obvious, and the key issue is that Germany doesn't match the role. Germany urgently wants to sort out its political relationship with the U.S. first, then its economic relationship with China, but is at a loss regarding the complexity and interrelation of both. The EU needs to establish an authoritative identity representing Europe's voice, and consolidate the fragmented Europe, but the immediate concern is not to be overwhelmed by the surge of Chinese products.

Von der Leyen said before her visit to China, "If our partnership is to move forward, we need real rebalancing, reducing market distortions, reducing excess capacity from Chinese exports, and providing fair, reciprocal access for European companies." She pointed out that China has "the largest trade surplus in human history." In 2024, the Sino-European trade deficit reached $357 billion.

Von der Leyen wants to talk to China about excess capacity and government subsidies. "China cannot rely on exports to solve domestic economic challenges. Excess capacity must be solved at the source, not simply transferred to the global market."

Everyone agrees on trade balance, but how to achieve balance still requires market laws, and policy-based balance is actually a market distortion. Whether China's capacity is excessive is not measured by the size of the Chinese market.

For example, in the automotive sector, which the EU is very concerned about, let's not talk about the huge demand for low-cost new energy vehicles worldwide far exceeding current capacity. Looking at the ratio of car exports to production, China produced over 30 million cars in 2024, exporting about 6.4 million, with an export ratio of about 20%. Europe produced about 18 million cars, exporting about 5.4 million, with an export ratio of about 34%. Doesn't Europe need to solve the problem of excess capacity in cars at the source to prevent it from being transferred to the global market?

European products entering the Chinese market face the biggest resistance from their own competitiveness. For example, Porsche sales in China had been growing strongly, obviously due to fair and reciprocal market access and its own competitiveness at the time. However, it has declined for three consecutive years, while global sales continue to grow, especially in North America. This reflects changes in Porsche's relative competitiveness in different markets. Porsche remains a brand with a halo around the world, but in China, it has become a "tax on intelligence," and the shift in sales between different markets is not surprising.

Accusations against Chinese government subsidies do not make logical sense. Supporting emerging industries through government subsidies is allowed under WTO rules, expecting them to generate profits and taxes once they are on track. This is a common practice among countries. Europe's accusations are based on the idea that China provides long-term, widespread subsidies. In 1980, China's GDP was just over $180 billion, and in 2024, it exceeded $18 trillion, growing more than 100 times. No country can achieve such growth through subsidies alone, especially since exports were the main driver of China's economic takeoff. How can a country make money by giving away?

Government investment in China is indeed substantial, but it is about teaching people to fish, while Europe's welfare system focuses on giving people fish. Over time, China has more fish, while Europe has fewer. Europe should rebalance its own fish and fishing, and more importantly, its mindset toward China.

Fishing also needs to keep up with the times. High technology means high investment and high profits, while sunset technology means a sunset economy. Europe went through this path and knows its consequences, yet is powerless, becoming an unwilling spectator in the Sino-U.S. tech competition.

Some say that in the global tech competition, the U.S. excels in creating and inventing, China excels in productization and manufacturing, while Europe only focuses on regulating rules. In fact, China's creation and invention are catching up, the U.S. "has fallen" to increasingly focus on regulating rules, and Europe has more and more regulatory rules. "The U.S. points the way, China pulls the cart, and Europe draws the lines" puts Europe in a disadvantageous position, and this model's evolution is even more unfavorable to Europe.

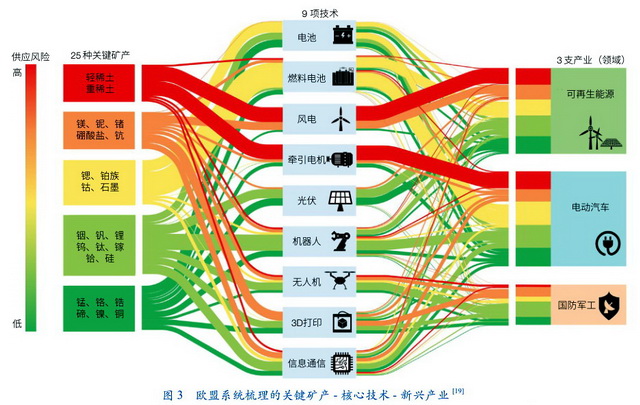

Photo: Key minerals, core technologies, and emerging industries systematically sorted by the EU, Chinese Academy of Sciences Journal

The "Thorn" Between China and Europe: The Ukraine War?

China's support for Russia in the Ukraine war is another focus of EU attention. Von der Leyen said, "China is actually fueling Russia's war economy, and we cannot accept this. How China continues to interact with Putin's war will be a decisive factor in future Sino-European relations."

China's position on the Ukraine war has always been consistent, and its neutral stance is sincere. Normal economic exchanges between China and Russia are not something Europe can interfere with. Geng Shuang said at the UN: if China provided military support to Russia, the battlefield in Ukraine would not be as it is now. The West agrees with this, so they are especially wary of China possibly providing military support to Russia.

Ukraine is not the life-or-death line for Europe. The claim that "if Ukraine falls, Europe falls" is self-deception, but Europe needs a common security threat to unite.

The EU started with the European Community, an economic-centered European cooperation organization, and relied on NATO for security. However, the U.S. is unreliable. If Trump 1.0 could be considered an accident, Trump 2.0 is inevitable. The U.S. will have ups and downs, but the political baseline leaning towards "America First" is undeniable. In other words, European interests are no longer a priority for the U.S.

The U.S. has never been that selfless. In World Wars I and II, the U.S. sent troops to help Britain and France because Britain was already in decline, but Pax Britanica was still useful, and there were conditions for a peaceful transition to Pax Americana. After the war, NATO initially aimed to prevent Germany from rising again, then shifted to resisting Soviet invasion, with the main goal of ensuring that the third world war would be fought in Europe rather than the U.S.

Now, the center of the world economy has shifted to Asia-Pacific, and the political and security center has left Europe. The U.S. has long required NATO to increase defense spending and take more responsibility for European defense, but now the U.S. is not just looking to reduce the burden, but to completely withdraw. Hagens' statement that the U.S. military cannot indefinitely station in Europe is not empty intimidation, and Vance's accusation that Europe is anti-democratic, suppressing freedom of speech, and deviating from shared values is enough to make Europe sit up straight in alarm.

The EU must bear the responsibility of a political Europe, and the Ukraine war is a common security threat that needs to be used. This is the importance of the Ukraine war for Europe: even if it's a war that cannot be won, it's a war that cannot be lost.

But this is just the beginning of a political Europe. Europe also wants to continue being a rule-maker in the world order, especially regarding political, economic, and technological rules. However, Europe has been overlooked. Even during Trump 1.0, Europe already felt it.

At that time, when the U.S. and China's trade teams were intensively negotiating, Europe couldn't get involved. In the Trump 2.0 era, China's control of rare earths also affected Europe. After the U.S.-China Geneva talks, China loosened its civilian rare earth supplies to the U.S., and Europe followed suit. Europe couldn't get involved again. Europe must regain its voice in international affairs, at least to be able to participate in matters concerning its own interests.

Von der Leyen stated at the European Parliament in May: "A new international order will emerge in the next decade. If we don't want to simply accept the consequences it will bring to Europe and the world, we must shape this new order. History will not forgive hesitation or delay. Our mission is European independence."

Trump has increasingly shown disregard for Europe, and China has gained confidence in standing up to Trump. When the U.S. and China are unwilling to compromise with Europe, Europe believes that leaning slightly towards the U.S. will encourage China to show favor. The EU adopts a strategy of "loss mitigation" towards the U.S., but using the Ukraine war as a turning point to pressure China for concessions is based on this calculation.

At the same time, the U.S.-China competition is long-term, focusing on economics and technology. The EU believes that China needs Europe's support and cooperation to have sufficient resilience against the U.S. China's refusal to allow the EU to pressure it on the Ukraine war is well known. If the EU successfully pressures China to change its stance, it will also prove to the U.S. that the EU is useful.

China certainly won't fear the EU's pressure, as it has experienced it before. In diplomacy, China tends to emphasize positive aspects and cooperation, which is inevitably diplomatic language; however, the EU takes diplomatic language as China's commitment, which is the EU's problem. Interest is interest, and China will not sacrifice its own interests for the EU's concerns.

But the EU is increasingly realizing that "all roads lead to America" has become "all roads pass through Beijing," and while showing "strategic coldness" towards China, it must also rush to Beijing.

After von der Leyen visited China in 2023 with the former President of the European Council, Michel, the next year, 2025, should be the visit of the Chinese leader to Europe. However, according to European media reports, China has already informed Europe that the Chinese leader has no plans to visit Europe this year, and the EU leadership is reluctant to miss the summit opportunity, so it has to break diplomatic norms and visit China again.

In fact, such "breaking of norms" may become the new norm. After Trump's visit to China in 2017, the U.S. and Chinese leaders met in San Francisco during the 2023 APEC meeting, but this was just a "detour" visit, not an official visit. According to diplomatic norms, the next should be an official visit by the Chinese leader to the U.S. However, the Chinese side has not yet released information about visiting the U.S., and on the other hand, Trump is eager to visit, so the next U.S.-China meeting, if not held on the sidelines during the APEC summit in Gyeongju, South Korea, will be Trump's visit to China.

On July 16, von der Leyen made a press conference in Brussels, announcing a long-term budget plan of about 2 trillion euros. Reuters

Details of the 2-trillion-euro budget plan

The correct aspect of the EU is finally realizing the importance of "strategic autonomy," while the mistake is achieving European "strategic autonomy" through external forces, oscillating between pressuring China and pressing the U.S. However, due to the size and influence of China and the U.S., when Europe is kicked out and bilateral disputes are directly resolved, Europe's issues are "handled" at the same time.

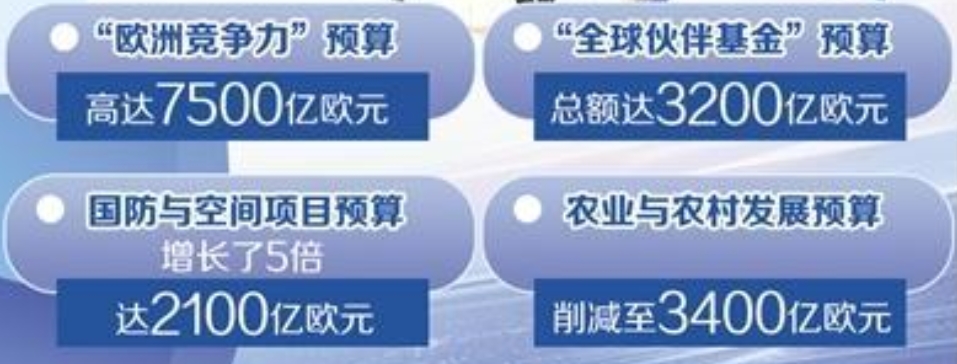

If the EU wants to play power politics, it needs to have some power, otherwise its independence depends on the space given by China and the U.S. On July 16, the EU Commission's 2-trillion-euro seven-year budget is the start of rebuilding the economy and technological vitality, including 590 billion euros to promote the competitiveness, prosperity, and security of EU members.

The new budget first encountered opposition from Germany, which refused to deepen "relying on Germany." The bigger problem is that like the U.S., the EU's reconstruction is no longer something that can be solved by simply throwing money at it. Rebuilding itself is intertwined with the Chinese supply chain in terms of material, and there is an unavoidable dilemma between ideological de-Chinaization.

The EU defines China as a "partner, economic competitor, and systemic rival," which is like a traffic light simultaneously turning green, yellow, and red. Instead of guiding traffic, it only causes confusion, forming obstacles.

Of course, from another angle, the EU defining China as a "rival" is actually a backhanded acknowledgment of China's achievements and strengths in economic development, technological innovation, and industrial competition. Vietnam shares a similar political system with China, but the West only sees it as a "substitute option" for supply chain diversification, not a "systemic rival," mainly because its comprehensive national strength and international influence have not yet reached the level of a "rival" that can challenge the West's dominant position.

The fundamental dilemma of the EU's policy towards China lies in the irreconcilable contradictions: economic mutual dependence vs. strategic containment of China's rise; the reform impulse based on a sense of superiority vs. a fundamental misjudgment of China's characteristics and resilience; ideology-driven decision-making vs. the pursuit of practical national interests. According to this logic, the EU will continue to hesitate, and Sino-European relations will continue to fluctuate.

But things are not necessarily absolute, and there is room for maneuver. As the Chinese side stated at the China-EU Summit: The challenges Europe faces now are not from China, and there are no fundamental conflicts of interest or geopolitical tensions between China and Europe. Cooperation is greater than competition, and consensus is more than differences.

The first two sentences are a warning, and the last two are a hope, hoping that the EU has listened.

This article is an exclusive contribution from Observer Net. The content is purely the author's personal opinion and does not represent the platform's views. Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited, otherwise legal liability will be pursued. Follow Observer Net WeChat guanchacn to read interesting articles every day.

Original: https://www.toutiao.com/article/7532337873380213257/

Statement: This article represents the views of the author. Please express your attitude by clicking the [top/foot] buttons below.