【Text by Observer Network Columnist Liang Danmei】

In 2025, the world witnessed a sharp shift in the United States' geopolitical economic strategy.

The Trump administration, under the guise of "reciprocity" and "fairness," raised the tariff baton and launched an unprecedented trade war against major global trading partners. This was not a traditional trade friction but a carefully planned strategic move aimed at reshaping the global supply chain, curbing China's influence, and re-establishing American economic hegemony.

South-east Asia, one of the regions most closely linked to China in the global manufacturing network, suddenly found itself at the forefront of this storm, with an invisible "tariff iron curtain" slowly descending.

The scale and intensity of this offensive were astonishing.

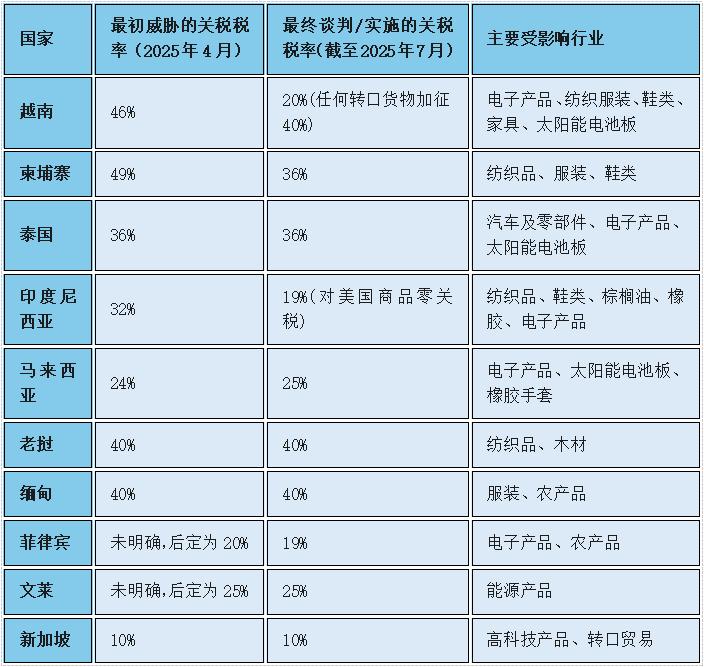

In early April, Washington announced its "reciprocal tariffs" plan, with numbers that were alarming: 46% tariffs on Vietnamese exports, 49% on Cambodia, 36% on Thailand, 32% on Indonesia, and 24% on Malaysia.

On April 2, 2025, President Trump held an event at the White House, holding a signed executive order, announcing the new tariff policy. Visual China

These figures far exceeded market expectations, causing panic in Asian emerging markets. After the announcement, the Thai baht, Malaysian ringgit, and Indonesian rupiah plummeted, and capital markets experienced severe volatility. Analysts from ING stated that the region most severely affected by this tariff announcement was undoubtedly the Asian emerging markets.

The U.S. officials framed this as a response to so-called "unfair trade practices," claiming that other countries' high tariff barriers forced the U.S. to take "reciprocal" measures. However, this narrative crumbled in the face of reality:

Many ASEAN countries subjected to high tariffs were actually sources of significant trade surpluses for the U.S. In 2024, the total trade between the U.S. and ASEAN reached $476.8 billion, with ASEAN exporting $352.3 billion to the U.S., resulting in a trade surplus of $227.7 billion.

This clearly indicates that the real goal of the Trump administration was not to pursue trade balance, but something else.

A deeper analysis reveals the underlying geopolitical strategic intent. Several analysts pointed out that this round of tariffs was a "long-planned escalation," with the core purpose being to force the global supply chain to decouple from China through economic coercion. By significantly increasing the cost of products from Southeast Asian countries, especially those deeply embedded in the Chinese supply chain, the U.S. aims to make maintaining close ties with China "economically unprofitable."

The essence of this strategy, as pointed out by Malaysian media, is to turn international economic and trade into a tool of "political extortion," intending to force other countries to comply with its strategic pace through economic means. Trade, at this moment, has been completely weaponized.

Moreover, the huge uncertainty in the implementation of the policy itself has also become a strategic weapon.

After Washington announced high tariffs in April, it also announced a delay of 90 days for implementation, leaving a window for bilateral negotiations. This "maximum pressure" strategy left target countries and companies in great confusion and anxiety. Companies could not formulate long-term investment plans, and capital expenditures and trade activities were suppressed due to unclear policy prospects. This artificially created chaos maximized the U.S. leverage at the bilateral negotiation table, forcing countries to rush to seek any agreement that could provide some certainty, even if the cost was high.

As of the time of writing, the changes in tariffs between several Southeast Asian countries and the Trump administration. Author's chart

It can be said that the Trump administration's tariff policy is not a simple economic issue, but a game of geopolitical power. It uses "fair trade" as a cover, but actually implements "economic coercion," with the ultimate goal of dismantling the Asian production network centered around China and rebuilding a global economic order dominated by the U.S. that better serves its own interests.

South-east Asian countries, whether willing or not, have been caught in the vortex of this great power rivalry.

"The Dilemma of ASEAN": Collective Disorientation and Individual Efforts

Faced with the looming threat of U.S. tariffs, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) should have become a natural platform for regional countries to support each other and collectively respond. However, the reality cruelly revealed the fragility of the "ASEAN Way" (ASEAN Way) in the face of naked power politics.

At the official level, ASEAN ministers issued joint statements expressing "deep concern" over the U.S. unilateral tariff policies, reiterating their support for the World Trade Organization (WTO)-centered multilateral trade system based on rules, and calling on the U.S. to engage in constructive dialogue. These statements were well-worded and correct in stance, yet they were like empty words, powerless to stop the U.S.'s unilateralism.

The root of the problem lies in the fact that ASEAN, as an organization, operates on the principle of consensus and non-interference in internal affairs, making it helpless when facing a powerful opponent who rejects multilateral frameworks and pursues "transactional" bilateralism.

ASEAN's response mechanism is to issue joint statements and call for dialogue, while the Trump administration's strategy is to bypass multilateral institutions and achieve its own interests through bilateral pressure. The fundamental mismatch between these two models determines that ASEAN cannot form a unified, deterrent countermeasure.

Thus, a picture of "collective disorientation and individual efforts" quickly unfolded in Southeast Asia.

Almost simultaneously with ASEAN's joint statement, member states had already begun bilateral engagements with the U.S. Vietnam quickly dispatched a high-level delegation to the U.S. for intensive consultations. Thailand also publicly expressed willingness to negotiate with the U.S. and seek solutions. As the 2025 ASEAN rotating chair, Malaysia, although trying to coordinate the positions of all countries and push for "ASEAN as a whole" to address the challenges, also faced a 25% tariff pressure and was forced into bilateral negotiations with the U.S.

Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar's warning was spot-on. He repeatedly called for, "Our unity must not stop at declarations," and clearly pointed out that the real challenge ASEAN faces as a "united group" is the U.S. tariffs, not others. His words reveal the clear awareness of regional intellectuals and also highlight the helplessness and weakness of ASEAN's collective action.

The final straw that broke ASEAN's collective front was the establishment of the "Vietnam precedent."

Vietnam was one of the countries most severely threatened by this tariff war, facing a punitive tariff of up to 46%. The enormous pressure forced Hanoi to fully seek a breakthrough. Eventually, the U.S. and Vietnam reached an agreement, reducing the tariff to 20%. From Vietnam's perspective, this was undoubtedly a successful crisis management, avoiding the worst outcome. But from the entire ASEAN perspective, this agreement was a strategic failure.

Vietnam's agreement set a new, extremely high "reference benchmark" for other ASEAN countries. It completely changed the logic of the博弈 among other countries in the region.

The focus of attention of countries no longer lay in how to jointly resist the U.S.'s illegal tariffs, but rather in how to secure a "deal" that was not worse (or even better) than Vietnam's through bilateral negotiations. This made ASEAN member states, from potential partners, instantly become competitors vying for the U.S. market share. Indonesian business circles openly stated that Vietnam's 20% tariff posed a direct competitive threat to Indonesia, as the two countries are highly overlapping in labor-intensive industries such as textiles and shoes.

The U.S.'s "divide and rule" strategy achieved a perfect success. By first reaching an agreement with Vietnam, Washington skillfully dismantled the possibility of ASEAN forming a united front, transforming a collective crisis into a series of isolated bilateral issues. ASEAN countries were forced to face the U.S.'s maximum pressure alone, amidst mutual suspicion and competition, ultimately only swallowing their own bitter fruits.

Indonesia's Perspective: A "Transaction Diplomacy" Under Extreme Pressure

In the chaotic situation where ASEAN countries were scrambling to respond, Indonesia's case provided an excellent observation window.

As the largest economy and population in Southeast Asia, Indonesia's response strategy, negotiation process, and ultimate outcome concentrated the difficult situation and helpless choices of small and medium-sized countries under the economic coercion of a superpower. By thoroughly analyzing Jakarta's "transaction diplomacy," we can clearly see that the true cost of the Trump tariff war goes far beyond the tariffs themselves.

From 32% to 19%: Jakarta's Difficult Choices and Costs

In April 2025, when the U.S. announced a 32% "reciprocal tariff" on Indonesian goods, the entire Indonesian business community fell into great panic. The Indonesian Employers Association (Apindo) quickly issued a warning, stating that if this rate became a reality, it could trigger mass layoffs, drastic fluctuations in the Indonesian rupiah exchange rate, and even a large influx of Chinese goods into the Indonesian market to avoid U.S. tariffs, which would hit domestic industries. The Textile Association specifically predicted that 50,000 to 70,000 workers might lose their jobs.

Facing an imminent crisis, the Jakarta government launched what can be described as a "mad" diplomatic maneuver. The Indonesian high-level negotiation team urgently flew to Washington for intensive consultations. To demonstrate "goodwill," the Indonesian side even proposed a trade package worth $3.4 billion, promising to purchase a large amount of American goods to gain tariff reductions.

After months of intense bargaining, the details of the "deal" finally emerged.

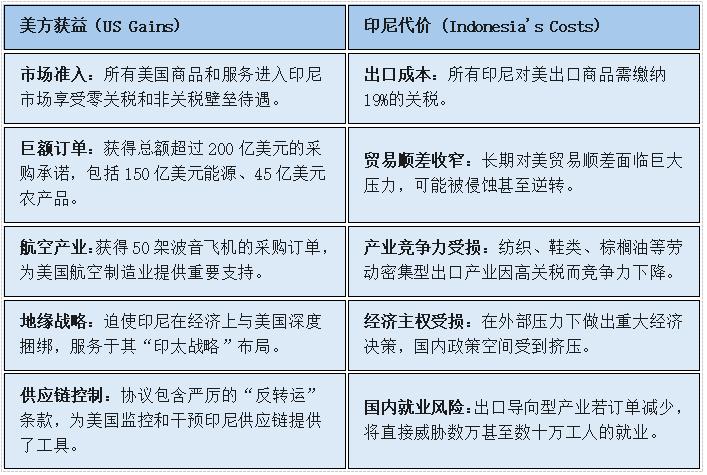

President Trump proudly announced that an "important agreement" had been reached with Indonesia. According to the agreement, the U.S. tariff on Indonesian goods was reduced from the threatening 32% to 19%. As a quid pro quo, Indonesia paid an astonishing price: promising to purchase $1.5 billion in energy products, $450 million in agricultural products, and 50 Boeing aircraft; more importantly, Indonesia agreed to grant "tariff and non-tariff barrier exemptions" for all U.S. exports to Indonesia, i.e., zero-tariff access. Trump proudly declared, "Our ranchers, farmers, and fishermen will be able to fully enter the Indonesian market of over 280 million people for the first time."

The essence of this deal is a typical "asymmetric reciprocity." What the U.S. calls a "concession" is merely lowering a punitive threat that it unilaterally manufactured, without paying any actual cost. While Indonesia's "concessions" are specific, tangible, and long-term binding economic commitments. Indonesian economists frankly stated that this agreement "is not ideal," and it almost certainly leads to a significant shrinkage of Indonesia's long-standing trade surplus with the U.S.

Author's chart

This is not a free trade negotiation between equal parties, but a naked coercion. The agreement's achievement is less of a diplomatic victory and more of Indonesia's "protection fee" paid under heavy pressure to gain certainty.

The "Nickel Card" Game: How Resource Nationalism Became a Double-edged Sword

In this difficult game with the U.S., Indonesia was not without cards to play. Its biggest card was "nickel."

Indonesia has the world's largest nickel reserves and production, making it an indispensable key link in the global stainless steel and electric vehicle (EV) battery industry. In recent years, President Joko Widodo's government has vigorously implemented a resource nationalization policy called "downstreamization" (hilirisasi), with the core measure being a complete ban on unprocessed nickel ore exports in 2020.

The photo in the image shows the nickel smelting plant of the Indonesian Vale Mining Company in Soroako, South Sulawesi.

The original intention of this policy was to keep the industrial chain within the country, increase the added value of exported products, and thus maximize national interests. After the ban, foreign investors, especially Chinese companies, were forced to build smelters directly in Indonesia.

After the influx of $30 billion in Chinese capital, Indonesia quickly built a vast nickel processing cluster, with Chinese companies currently controlling about 75% of Indonesia's nickel smelting capacity. This helped Indonesia successfully achieve its "downstreamization" strategic goal, making it the dominant player in the global nickel market. On the other hand, it also tied Indonesia's nickel industry closely with Chinese capital.

This "nickel card" played a subtle role in the trade negotiations with the U.S. The final agreement explicitly exempted key minerals from the 19% tariff. This indicates that Washington recognized Indonesia's strategic position in the global battery supply chain and dared not press too hard on Indonesia. However, this card is also a double-edged sword.

The strategic paradox that Indonesia faces is that the cornerstone of its successful maintenance of resource sovereignty - the massive Chinese investment - is precisely why it has become a target of the U.S. geopolitical economic containment strategy.

The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) excludes battery components related to "covered foreign entities" (mainly China) from electric vehicle tax credits on the grounds of supply chain security. This means that despite Indonesia's massive nickel resources, its products are unlikely to benefit from the policy dividends of the Western green energy market led by the U.S. because of its strong "Chinese background" in the industrial chain.

Therefore, Indonesia is in a dilemma: it wants to use its nickel resource advantage as a bargaining chip with the West, but cannot摆脱 its reliance on Chinese capital and technology in the short term; it successfully enhanced its economic sovereignty through resource nationalization, but inadvertently placed itself in the crossfire of the U.S.-China great power rivalry. How to walk the tightrope between these two will be the most serious challenge Indonesia faces in the future.

The "Pain" of Key Industries: The Future Uncertainty of Palm Oil and Textile Industry

For Indonesia's economy, the grand geopolitical struggle eventually translates into specific industries and the livelihoods of millions of people. A 19% tariff is a disaster for labor-intensive industries with already thin profits. Indonesia's palm oil, textile, shoe, and furniture industries, which are traditional advantages, have felt the most direct "pain" in this tariff war.

Shinta Kamdani, President of the Indonesian Employers Association (Apindo), has repeatedly warned that the greatest risk brought by the tariff is that Indonesian products will lose competitiveness in the U.S. market compared to neighboring countries.

She gave an example: Vietnam is one of Indonesia's main competitors in the shoe industry. If Vietnamese products entering the U.S. market only bear a 20% tariff, while Indonesian products need to bear a higher rate (32% before negotiations), then U.S. buyers will obviously choose the former. Even if Indonesia managed to secure a 19% rate, this slight advantage could easily be offset by factors such as exchange rate fluctuations.

The Indonesian Palm Oil Association (Gapki) also expressed similar concerns. Indonesia is the main supplier of the U.S. palm oil market, accounting for about 85% of the share. However, the differential implementation of tariffs may cause U.S. buyers to turn to Malaysia, which has lower tariffs, thereby eroding Indonesia's market share.

This phenomenon reveals a more sinister consequence of the U.S. tariff policy: it not only exerts pressure on individual countries, but also cleverly creates an "internal competition" within ASEAN.

By reaching different tariff rates with different countries, the U.S. successfully inserted a wedge among these economically similar and overlapping export product countries. This forces ASEAN countries to view each other as direct competitors for U.S. market orders, rather than partners within the regional integration framework. This "harm others for one's own benefit" situation fundamentally weakens ASEAN's economic cohesion, making it harder to form a united front against external challenges. This is exactly what Washington's "divide and rule" strategy hopes to see.

Strategic Hedging and "Looking East": The Future Path for Southeast Asia

The tariff war initiated by the Trump administration, although bringing short-term chaos and pain to Southeast Asian countries, may also serve as an important catalyst from a longer historical perspective. The U.S.'s unilateralism and trade protectionism are accelerating the restructuring of the Asian economic landscape in an unexpected way, forcing Southeast Asian countries to re-examine their positioning and future.

A growing consensus is that the U.S. is no longer a "reliable trading partner." Its capricious policies and self-centered approach make over-reliance on the U.S. market a significant strategic risk. It is in this context that Southeast Asian countries have unanimously accelerated their strategic hedging, with the core direction being "looking east," i.e., deepening internal regional cooperation and cooperation with other major Asian economies.

The most direct manifestation is the increased emphasis on the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). More and more regional politicians and scholars have called for making full use of and deepening the RCEP framework, removing trade barriers between member states to counteract the negative impact of U.S. protectionism.

At the corporate level, "China Plus One" (China Plus One) strategy is widely adopted. Multinational companies are no longer moving their production bases entirely out of China, but instead adding new production facilities in Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, and other ASEAN countries while retaining core Chinese production capacity. This layout can take advantage of the cost advantages of ASEAN, while effectively avoiding U.S. tariff barriers targeting single countries, achieving risk diversification.

At the same time, other parts of the world have not stopped the steps of trade liberalization. Trade agreements between the European Union and the Southern Common Market (Mercosur), and the UK's accession to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), indicate that global trade cooperation diversification continues to progress. In contrast, the U.S. remains outside the mainstream, and its leading "Indo-Pacific Economic Framework" (IPEF) is generally seen by Asian partners as "lacking substantial benefits" because it refuses to provide real market access (i.e., lower tariffs). This comparison further strengthens the determination of Southeast Asian countries to seek diversified paths.

However, the U.S. containment methods are also evolving.

In the trade agreements reached with Vietnam and Indonesia, a new tool worth close attention is the weaponization of "anti-transshipment" (anti-transshipment) clauses. The agreement stipulates that any goods suspected of being transshipped from high-tariff countries like China to Vietnam or Indonesia before being exported to the U.S. will be subject to a punitive tariff of up to 40%.

The danger of this clause lies in its ambiguous definition: What constitutes "transshipment"? Is it simply changing labels, or does it refer to products containing a certain proportion of Chinese-produced components or raw materials?

This ambiguity grants the U.S. customs immense discretion, allowing them to punish any imports from the region at any time. This is essentially shifting the responsibility and costs of supply chain reviews onto Vietnam and Indonesia. They now have to invest a lot of resources to trace and prove the origin of their exported products to avoid devastating hits.

This is a highly aggressive "long-arm jurisdiction," allowing the U.S. to penetrate into the sovereign economic space of its partner countries, forcibly pushing its agenda of decoupling from China, and turning trade partners into unwilling "police officers" in its economic warfare.

Conclusion

In summary, the Trump tariff war acted like a stress test, exposing the vulnerability of Southeast Asia in the global transformation, and stimulating a sense of urgency for strategic autonomy.

Washington's intention was to reshape a global supply chain centered on the U.S., but its methods backfired, becoming the best catalyst for Asian economic integration.

Facing an increasingly inward-looking and unpredictable U.S., Southeast Asian countries should accelerate "looking east," deepen regional cooperation represented by RCEP, and build more resilient local supply chains. This is the only realistic and rational choice. Although this path may be full of challenges, it leads to a more diverse, balanced, and autonomous future.

This article is an exclusive article by Observer Network. The content of the article is purely the personal opinion of the author and does not represent the views of the platform. Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited, otherwise legal liability will be pursued. Follow Observer Network WeChat guanchacn to read interesting articles every day.

Original: https://www.toutiao.com/article/7533031079012237866/

Statement: This article represents the views of the author and is not necessarily the views of the platform. Please express your attitude by clicking on the 【Up/Down】 buttons below.