On January 26, 2026, the European Union Council passed a historic resolution by an overwhelming majority, banning all Russian liquefied natural gas (LNG) from entering the EU market starting January 1, 2027. Eight months later, Russian pipeline gas will be completely cut off. This not only marks the largest energy strategy shift in the EU since the oil crisis of the 1970s but also represents an open declaration of Europe's geopolitical autonomy in the post-Cold War era.

Russian LNG facilities

Certainly, this decision did not come suddenly. Since the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine conflict in 2022, the energy ties between the EU and Russia have gradually weakened through multiple rounds of sanctions and countermeasures. However, this "complete severance" decision, with its clear timeline and irreversible nature, has disrupted the global energy landscape, triggering a series of geopolitical turbulence that is spreading from Europe to every corner of the world.

Geopolitical Driver

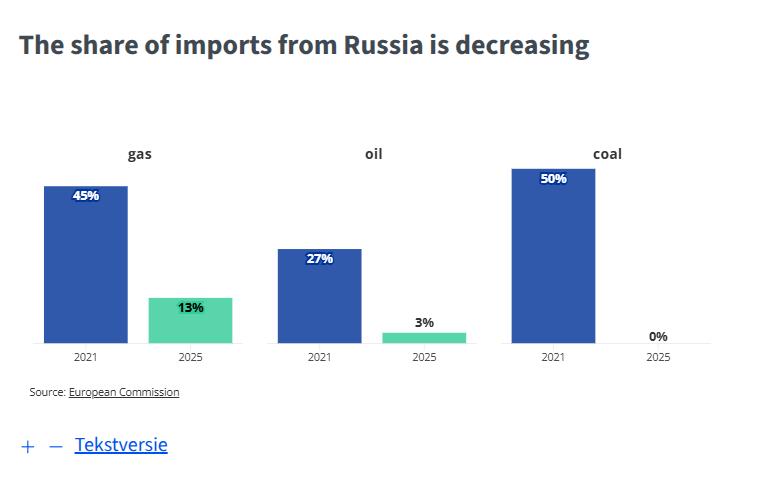

EU-Russia gas import share is decreasing (screenshot from the EU Council website)

From the result, the EU's ban on Russian gas is due to multiple factors, but geopolitics is the direct driver of the decision.

Specifically, since the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine conflict in 2022, the EU has imposed multiple rounds of sanctions on Russia, with the energy sector being the core battlefield of their rivalry. This ban marks a fundamental shift in Europe's energy security mindset, from economic rationality of mutual dependence with Russia to geopolitical considerations oriented towards strategic autonomy.

Since the 21st century, the EU and Russia have formed a deep energy interdependence pattern. By 2021, Russian gas accounted for about 45% of the EU's total imports, and in some East European countries, this proportion exceeded 80%. This dependency was seen as a model of economic complementarity between Russia and the EU during peacetime, but it quickly turned into a strategic vulnerability during geopolitical crises.

The risk of energy weaponization since 2022 has forced the EU to reevaluate its traditional belief of "changing through trade." The passage of the ban essentially marks the formal end of the EU's "détente policy" toward Russia in the post-Cold War era, a landmark event where geopolitical reality overrides economic pragmatism.

Schematic diagram of Russian-EU gas pipelines

From the perspective of Europe's demand for strategic autonomy, the Russia-Ukraine conflict has exposed the "Achilles' heel" of European energy security. EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has repeatedly emphasized, "Energy security must not become a tool of external coercion." This ban is a concrete practice of the EU's pursuit of "strategic autonomy" in the energy field, aiming to completely free itself from over-reliance on a single supply source. The underlying logic is that economic interests must yield to strategic security. The EU is trying to declare to the world its new principle of placing energy sovereignty above market liberalism.

With the implementation of the ban, it also reflects the deepening coordination between the US and the EU on the stance toward Russia. As the EU's main ally, the US has continuously pressured Europe to completely rid itself of reliance on Russian energy. At the same time, the EU has cautiously maintained its own decision-making autonomy, avoiding being seen as merely executing the agenda of the US government. The timing and scale of this ban are the result of months of intensive diplomatic negotiations between the US and the EU, satisfying the US's demand for maximum pressure on Russia while leaving an adaptation window for the EU's vulnerable economies.

Energy Patterns and Economic Costs

American LNG ships

For the EU, the most direct and urgent challenge of the Russian gas ban lies in two aspects: energy supply diversification and infrastructure adjustment. Since the partial interruption of Russian gas in 2022, the EU has accelerated the restructuring of its natural gas supply map.

Firstly, the acceleration of supply diversification. The United States has become the main supplier of liquefied natural gas (LNG) to the EU, accounting for nearly 45% of the current EU LNG imports. This shift not only changed the direction of energy flows but also reshaped the economic basis of transatlantic relations. At the same time, Norway, as a stable and reliable partner, currently provides more than 33% of the EU's pipeline gas supplies, and its importance has further increased.

Schematic diagram of Caspian gas islands between Europe and Central Asia

Additionally, the EU is actively exploring other sources, including increasing imports from Azerbaijan, Algeria, and Qatar. Notably, the planning and construction of the trans-Caspian gas pipeline have been accelerated. This pipeline, referred to by some European policymakers as the "next major energy artery," aims to transport Central Asian gas through Turkey to Europe. However, this route still faces multiple challenges, including geography, politics, and financing, and inevitably passes through geographically sensitive areas in Central Asia, making it susceptible to indirect influence from Russia.

In terms of infrastructure upgrades, the EU still needs to make significant investments. The EU's natural gas infrastructure was originally optimized for receiving Russian westward pipeline gas. The ban forces Europe to carry out costly "reverse modifications," mainly including accelerating the construction of LNG receiving stations along the coast and modifying pipelines to adapt to southward and westward gas sources.

According to estimates by the Belgian Bruegel Institute, emergency investments in EU natural gas infrastructure between 2022 and 2027 will exceed 100 billion euros. Moreover, grid upgrades, energy storage facilities, and supporting grids for renewable energy will require additional billions of investments. These costs will eventually be passed on to European businesses and ordinary citizens through energy prices.

European chemical industry workers

After the implementation of the Russian gas ban, the EU will bear significant economic costs and inflation pressures. Although the EU has passed the most severe energy crisis between 2022 and 2023, the long-term economic impact of the full ban remains no small matter. European industries, especially traditional energy-intensive sectors such as chemicals, steel, and fertilizers, will continue to face higher energy cost pressures compared to American and Asian competitors, leading to a decline in European industrial competitiveness and potential risks of industrial relocation.

Furthermore, although household energy expenses in Europe have decreased somewhat due to diversification, they will remain significantly higher than pre-Ukrainian crisis levels for a long time, continuously squeezing consumer spending. An internal assessment report from the European Commission warns that the ban could lower the EU's GDP growth rate by 0.5 to 1 percentage points annually and increase structural inflation levels.

Natural gas pipeline in Hungary

There are obvious divisions and internal differences within the EU regarding the ban. Countries in Central and Eastern Europe, such as Hungary and Slovakia, are highly dependent on Russian energy, with their industrial systems and home heating systems built around Russian gas, resulting in high transformation costs, and therefore clearly oppose the "one-size-fits-all" ban. As a compromise, the EU has established temporary exemptions and special transition funds for certain member states, but the fundamental contradictions remain unsolved.

Western and Northern European member states, which started energy transitions earlier and have more alternatives, hold a more positive attitude toward the ban. This division is not only economic but also political, testing the EU's principle of "unity," and may lead to deeper governance challenges in future crises. The adoption of the ban has not resolved the internal rifts within the EU, but rather planted the potential for EU fragmentation in the energy transition process.

Global Impact and Implementation Prospects

China-Russia Eastern Gas Pipeline

The EU's ban on Russian natural gas is not just a regional energy policy adjustment; it will trigger a chain reaction in the global energy market and reshape relevant geopolitical landscapes.

As one of the world's largest natural gas import markets, the EU's complete shift will permanently change the global LNG trade pattern. Russian gas will be forced to shift massively to the Asian market, especially China, India, and Southeast Asian countries. This increases competition for global LNG resources, drives up benchmark prices in the Asian market, and tilts the balance of long-term contract negotiations in favor of suppliers.

European ports accepting stored LNG

At the same time, major LNG exporters such as the United States, Qatar, and Australia will compete fiercely for the European market share, triggering a new wave of investment in liquefaction facilities. However, whether the global LNG production capacity can catch up in time before 2027 remains uncertain, and there may be market tensions in the short term.

Meanwhile, the United States plays a dual role in the EU's energy transition. The US is both a "fire brigade" for European energy and a "beneficiary" of LNG exports. On one hand, U.S. LNG will quickly fill the European energy gap, claiming to provide energy security "backing" and strengthening the transatlantic security bond. On the other hand, policies such as the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act offer substantial subsidies for domestic green industries, attracting European companies to invest, attempting to integrate the EU's green industry into its own supply chain, raising deep concerns in Europe about "deindustrialization."

President Putin of Russia with leaders of the five Central Asian countries

Finally, in the context of the Russian gas ban, the Central Asian region's position in the EU's energy strategy has rapidly risen. Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and other countries have rich natural gas resources, becoming key targets for the EU to achieve supply diversification. The EU is vigorously promoting the expansion of the "Southern Gas Corridor" bypassing Russia, particularly the trans-Caspian gas pipeline project. This has prompted the EU to increase diplomatic, economic, and technological investments in the region, aiming to build closer energy partnerships.

However, this move is undoubtedly a violation of Russia's traditional sphere of influence, and the Central Asian region may become a new focal point of geopolitical competition between Russia and the West. Of course, it is also possible that Central Asian countries try to maintain a balance between multiple parties to gain maximum benefits. However, overall, the energy industry of Central Asian countries is deeply integrated with Russia, and the EU will find it difficult to achieve the goal of extracting natural gas benefits from Central Asia without going through Russia.

An Era Ends and Future Uncertainties

The EU's comprehensive ban on Russian natural gas marks the complete end of an era driven by cheap Russian gas for European industry and warmth. It is a gamble by Europe to pursue energy sovereignty and security at the cost of economic price. It will continue to put pressure on Europe's economic competitiveness, internal unity, and social stability for several years to come, and will trigger waves of restructuring in global energy trade, industrial competition, and geopolitical alliances.

Although the EU leadership has shown firm political will, the full implementation of the ban still faces many challenges. First, the practical test of supply security, the winter of 2027-2028 will be the first heating season without any Russian gas, and whether the new supply sources and infrastructure are ready will be tested in practice.

Second, the political test of social endurance, if energy prices surge again due to global market fluctuations, the public's tolerance and the ability of governments to respond will be tested, possibly fueling right-wing populist political forces. Finally, the legal and enforcement challenges, specific implementation details of the ban, handling of existing long-term contracts, and regulation and punishment of violations need to establish strong enforcement mechanisms between the EU and member states to implement the ban.

The EU's "winter" test will not only be a physical temperature, but also a comprehensive test of Europe's economic resilience, political unity, and strategic perseverance.

Original: toutiao.com/article/7600217796018848282/

Statement: The article represents the views of the author.