Under the threat of "Liberation Day" tariffs from Trump, many countries are rushing to reach agreements with the United States, while BRICS countries such as Brazil, India, China, and South Africa have chosen to "resist firmly," what impact will this have on the global multipolar structure?

This episode of PacificPolarity invites Paulo Nogueira Batista, a Brazilian economist. As a former Executive Director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for Brazil (2007-2015) and founding Deputy President of the New Development Bank (NDB), headquartered in Shanghai (2015-2017), Batista has deeply participated in international financial governance and authored works such as The BRICS and the Financial Mechanisms They Created. His dual experience provides a unique perspective for examining the current global financial power structure.

According to Batista, Trump's "reciprocal tariffs" policy deliberately targets BRICS countries (with Brazil and India facing 50% tariffs, and China and South Africa 30%), motivated by viewing the BRICS as "opponents" and "anti-American forces," aiming to suppress their efforts to challenge the dominance of the U.S. dollar and create alternative currencies. This move may objectively strengthen the internal cohesion of the BRICS.

Secondly, there is a fundamental difference between the IMF and the NDB: the IMF is controlled by the West, especially the United States, and has become a geopolitical tool; while the NDB is led by the BRICS five countries, representing the interests of developing countries. He sharply pointed out that since the 2010 voting rights reform, the IMF has been stagnant for 15 years, with the West abandoning its reform commitments. The root cause lies in the fact that the West views the IMF as a political weapon and is unwilling to grant emerging powers like China the appropriate voice, resulting in a highly distorted governance structure.

Batista's judgment of complete disappointment with IMF reforms and his emphasis on the development of alternative mechanisms such as the NDB point to the growing dissatisfaction and centrifugal forces among the Global South with the existing Western-dominated, unfair international financial system. This structural contradiction is driving the acceleration of the restructuring of the international financial power structure, making it an inevitable trend for emerging forces to seek a more just and non-unipolar new order.

Photo: Paulo Nogueira Batista Jr.

Li Zexi: Welcome to this episode of PacificPolarity. Today, we have invited Paulo Nogueira Batista Jr. He is a Brazilian economist who served as an Executive Director at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) from 2007 to 2015, responsible for Brazil and other countries. He was also one of the founders of the New Development Bank (also known as the BRICS Bank), which is headquartered in Shanghai, and he served as Deputy President from 2015 to 2017. He has written seven books and numerous economic papers and publications, including The BRICS and the Financial Mechanisms They Created and The Way Out of IMF Reforms. Paulo, it's a pleasure to have you on the show.

Batista: Thank you, I'm glad to be part of this conversation.

Li Zexi: Perhaps we can start with recent news: Trump's "reciprocal tariffs" have officially taken effect. One thing people noticed is that, whether intentionally or not, the BRICS countries seem to have suffered significantly. Evan Feigenbaum recently pointed out that many countries are rushing to reach agreements with the United States, while Brazil, India, China, and South Africa have chosen to "resist firmly." He believes that Trump has made a "significant contribution" to the BRICS in this regard. What do you think about this?

Batista: I believe the BRICS countries have indeed suffered significantly. The tariff rates on some goods from Brazil and India are as high as 50%, and some even slightly higher. South Africa faces a 30% tariff, and China currently also faces a 30% tariff. As for Russia, it has been under sanctions since the outbreak of the Ukraine conflict, so it has little trade or at least no trade within the scope of tariffs understood by Trump.

So yes, I believe the BRICS countries are being deliberately targeted, and Trump himself has given reasons. He has repeatedly stated that he sees the BRICS as opponents, hostile forces, anti-American forces. He has consistently emphasized that the BRICS must abandon their efforts to challenge the status of the U.S. dollar as a reserve currency and to create alternative currencies.

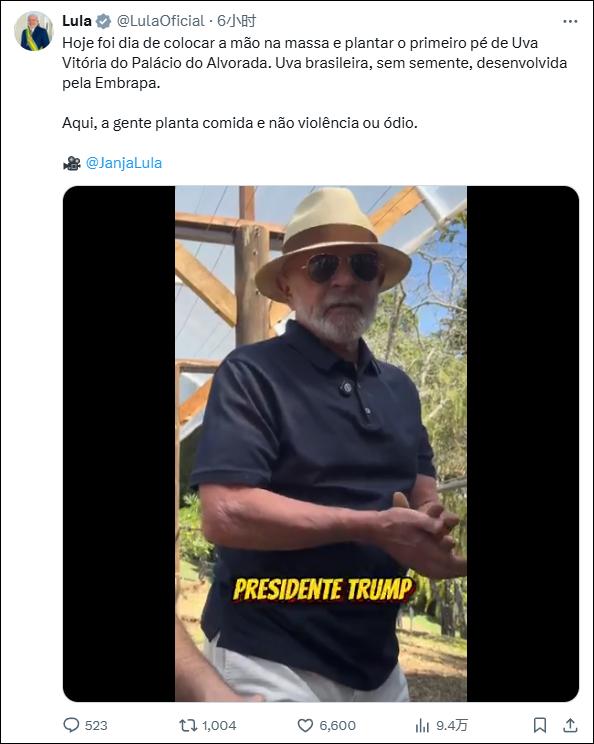

Recently, Brazilian President Lula posted a video of himself planting grapes (a product affected by tariffs) and addressed Trump, suggesting he come to Brazil to talk. Social media

His recent actions have also been surprising. Take Brazil as an example, which is a very special case, because the reasons Trump gave have little to do with trade; the U.S. imposes a 50% tariff on more than half of Brazil's exports to the U.S., mainly based on non-trade factors, such as the so-called "political persecution" of Brazil's former president Bolsonaro—Trump's close ally, or even a vassal; he also mentioned the restrictions on large tech companies by the Brazilian Supreme Court; and concerns about the Brazilian instant payment system "PIX" weakening the market share of American credit card brands (especially Visa and MasterCard). This is a strange situation.

As for India, this is particularly important strategically. Trump suddenly hit India hard, which is critical for the BRICS. It is well known that India considers itself to have a special relationship with the U.S., which has influenced its attitude within the BRICS. However, it seems that this so-called "special relationship" might just be India's fantasy, as it did not prevent the U.S. from imposing a 50% tariff on India, which would almost cut off trade. Therefore, although Trump caused significant damage to trade and the economy, he may have inadvertently strengthened the cohesion of the BRICS, and I hope the situation will develop in this direction.

Li Zexi: Let's talk about your background. You have worked at both the IMF and the New Development Bank (NDB), and both institutions have the common goal of providing loans to countries in need, but they differ greatly in structure and operation. You have held leadership positions in both institutions. What do you think is the most important difference between them in actual operations?

Batista: The nature of these two institutions is different. The IMF primarily aims to provide international balance of payments support and macroeconomic support to countries facing international balance of payments or other economic difficulties. The New Development Bank, headquartered in Shanghai, is more similar to the World Bank, a development bank whose main function is to support infrastructure and sustainable development projects. The NDB was negotiated by the BRICS countries between 2012 and 2014, aiming to replace the World Bank, not the IMF.

But the biggest difference between the IMF and the NDB lies in their political attributes. The IMF is controlled by the West, especially the United States and its allies, and is a political tool of the West; while the NDB is a bank established by developing countries for developing countries, jointly controlled by the five founding member states—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. Therefore, in terms of political significance, it is a completely different type of institution, with goals fundamentally different from those of institutions headquartered in Washington, dominated by the West (mainly the IMF and the World Bank).

Li Zexi: When you were at the IMF, you pushed for reforms from 2008 to 2010, which shifted voting rights towards developing countries. However, since then, despite the continued transfer of global economic power from the "Global North" to the "Global South," there have been no further reforms. You recently commented that a key reason for the lack of further reform is that any new reform could increase China's voting share, which the Western countries would oppose. So, is it possible for the West to propose a reform plan that increases the voting rights of small developing countries (at the expense of developed countries), while keeping China's voting rights basically unchanged as an emerging superpower with parts of its territory highly developed? How would developing countries react to this? And how would this affect the BRICS and China's interactions with the Global South, especially in the context you mentioned: one of the core reasons why developing countries are interested in a potential new world order is their dissatisfaction with the lack of reform in Washington-based development institutions?

Batista: I had the opportunity to participate in the reforms of 2008 and 2010, as you said, these reforms shifted voting rights from developed countries to emerging markets and developing countries, i.e., from the Global North to the Global South. But these reforms did not fundamentally change the governance structure. China's share increased, as did Brazil's, along with other countries, but the institution is still controlled by the West, basically by the United States and its European allies. As you said, there has been no progress for 15 years since 2010.

In April this year, U.S. Treasury Secretary Bensons "attacked" the IMF and the World Bank for being too close to China

During this time, Western countries—Europeans and Americans—abandoned their commitment to further reform the IMF. These were written commitments made by leaders, which were shamefully ignored by the Westerners. I remember asking Americans and Europeans in the Executive Board meetings, at the time the Managing Director was Christine Lagarde, and I told them, "Your statements now contradict the documents signed by the leaders." But their response was as if they had never made any commitments.

It is no coincidence that the BRICS countries started to create their own mechanisms—the New Development Bank in Shanghai and the Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA)—after experiencing major betrayals by the West.

Reforms have stagnated. Let me add one more point: not only has the IMF reform been stagnant for 15 years, but in the foreseeable future, there will be no fundamental reforms in the IMF and the World Bank either. The reason is that Western countries insist on controlling the World Bank and the IMF, considering them political weapons and geopolitical tools.

You mentioned a question: can we at least increase the voting rights of small countries without touching the Western opposition底线? Theoretically, it is possible. There are two methods in the existing structure of the IMF: one is to increase basic votes (basic votes), so that all small countries, whether developed or developing, will benefit; the second is to increase the compression factor in the quota formula to favor small countries.

But these measures have limited significance. Why? Because they must be designed not to touch a fundamental principle in the IMF architecture: the United States is the only country with a veto power (major decisions require 85% majority, and the U.S. share must always be above 15%). Any reform that would lower the U.S. share below 15% would be automatically vetoed by the U.S.

Regarding China, you are right. China is the most underrepresented country in the IMF and the World Bank according to any indicator. Therefore, any meaningful reform must significantly increase China's share in the IMF and the World Bank. But will the U.S. and Europe agree? No, they see China as their main rival and are unwilling to give China more space in their controlled institutions. Therefore, China will continue to have insufficient shares in the IMF and the World Bank, and this will not change.

Certainly, I am not saying that the IMF cannot improve its operations. I published a paper last year proposing some adjustments that I believe are feasible, which do not touch the U.S. and European veto line. Others have similar proposals, but these adjustments will not fundamentally change the governance structure.

This is exactly why developing countries, the BRICS countries, need to think about alternative mechanisms. We need to further develop the New Development Bank in Shanghai and promote the Contingent Reserve Arrangement to become more effective. At the recent BRICS summit in Rio, there have been some advances, as the leaders put forward beneficial guidance for the New Development Bank and the Contingent Reserve Arrangement in the Rio Declaration. If implemented, this will help make them more meaningful than they are now.

Li Zexi: I asked this way because I feel that since the West seems to be increasingly focused on containing China, they might be willing to consider reforms of institutions like the IMF and the World Bank to win over other countries in the Global South to their side. Obviously, in the past few years, the West, especially the U.S., has increasingly talked about the "Global South"; at the same time, China has also focused on the Global South. Does this give the West the motivation to empower smaller countries in the Global South?

Batista: I don't think so; they basically want to freeze the governance structure in the status quo and act according to their own will. If necessary, they will selectively assist some countries in the Global South; but note that it is selective. This means it is not equal. Whether a country in the Global South can get assistance depends on whether it is close to the West, the U.S., and Europe. For example, a country that is independent and trying to go its own way may face great difficulty in getting support from the IMF and the World Bank, which often happens. On the contrary, if a country is obedient to the U.S. and the West, like Argentina now, it may find it easier to get support from the IMF and the World Bank.

From a geopolitical perspective and our independence as BRICS countries and emerging markets, this situation is unacceptable. This issue existed during my tenure, that is, lack of fair treatment. For example, Ukraine, because it is needed to weaken Russia, can get everything it wants; regardless of how indulgent its macroeconomic policies are, it can still get funds from the IMF and the World Bank. In contrast, Serbia, although it may need support, because it is considered to be too close to Russia, its requests will not even be discussed in the Executive Board. This is a highly distorted situation. Frankly, I am sorry, because I tried to push the IMF to become a 21st-century institution during my tenure from 2007 to 2015, we achieved some progress, but failed to achieve this major goal. I believe this goal will not be achievable in the foreseeable future.

Therefore, I reiterate again, the BRICS countries, especially China, which has stronger organization, must seriously consider establishing alternative mechanisms, not only to replace the World Bank and the IMF, but also to replace the entire Western-dominated monetary and financial system, because this entire system has been distorted into a tool of power, suppression, and discrimination, which is everywhere.

Li Zexi: A common complaint in the Global South—indeed, not only the Global South—is that IMF loans come with many conditions. The IMF may argue that these conditions are necessary, as they want the recipient countries to follow a better, more sustainable growth path. But critics argue that this may be to promote Wall Street interests, such as facilitating capital flight and weakening the competitiveness of recipient countries against Western companies. As someone inside the institution, what do you think is the real reason behind the IMF's insistence on conditions? Do you think this practice will change, given that it is so unpopular in the Global South?

Batista: I agree with your summary of the IMF's official statement and the critics' views, both of which have some merit. As an institution, the IMF must ensure that borrowing countries are capable of repaying, which means it must see that these countries are implementing sustainable economic policies, as you said.

On the other hand, the critics are also right, because when the IMF imposes conditions, it often ignores the particularities of each country and overlooks political limitations. Especially worth emphasizing is that the IMF's approach is highly unjust: if you are a favorite of the West, even if you implement many macroeconomic policies that are problematic, you can still pass the IMF; but if you are independent and not favored by Washington, Brussels, London, and Paris, even with a solid adjustment plan, it is difficult to get support.

This lack of fairness is severe enough to undermine the theoretical foundation of the IMF—there is nothing wrong with the theory that funds should not be given unconditionally, and macroeconomic policy adjustments should be accompanied—but when you work within the institution for many years, you find that this theory is extremely imbalanced and unfair in practice, leading to a loss of institutional credibility.

And this imbalance exists precisely because the IMF's governance structure is distorted, making it actually a "North Atlantic Monetary Fund" instead of an International Monetary Fund. As my Indian colleague Rakesh Mohan said in the Executive Board meeting: this is a North Atlantic Monetary Fund, not an International Monetary Fund. This is the reality.

New Development Bank President Rosell said that if more countries in the Global South actively learn from China's modernization experience and strengthen international cooperation, it will better promote socio-economic development. WeChat official account "New Development Bank"

We must stop the illusion of reform, this change will not happen. We can continue to repeat the standard rhetoric about making the IMF and the World Bank more representative, but we must be clear that this will not be achieved. We must formulate our own action plans under the premise of fully understanding what can happen and what is absolutely impossible within the Washington system.

Li Zexi: The New Development Bank (NDB), also known as the BRICS Bank, also faces representation issues: the collective voting rights of the five founding members must be no less than around 55%. You once pointed out in an interview that this undoubtedly hinders the admission of new members. Why is this set up this way? Is it to institutionalize the consolidation of the power of the founding members, similar to what you previously said about the West's control of the IMF, except that here it is an explicit arrangement, whereas there it was an implicit one?

Batista: I agree, the purpose is to consolidate the power of the five founding members. But I think this was a mistake we made back then: the 55% minimum ratio is too high. Under this structure, the bank may only attract some small countries that are not concerned about voting rights, which see the NDB as a source of financing; but it is difficult to attract large emerging markets and developing countries like Indonesia. Indonesia is a country with the fifth largest population and tenth largest GDP, why would it accept a much lower share than South Africa? South Africa is far smaller than Indonesia in terms of land area, GDP, and population size. To attract Indonesia, Turkey, and other countries, it is difficult under this structure. I don't think this is the only reason for the slow expansion, but it is definitely a significant factor, stemming from a mistake during our negotiations.

Li Zexi: Regarding loan conditions, the NDB has always emphasized that its approach is the opposite of the IMF, and it does not impose any conditions on its loans. Will this increase the risk of mismanagement of funds? What is the ideal middle ground?

Batista: Actually, it's not entirely true. Our original intention (written into the strategic documents and bylaws) was to respect the policy framework of the borrowing country, unlike the IMF or the World Bank, which "reform" other countries' economies. We set project conditions and monitor project progress, but this is project-oriented, not interfering with macroeconomic policies. We are not "saving countries," but helping countries and respecting their policy choices.

But does this philosophy get implemented? I'm not sure. Because one weakness of the NDB is its low transparency, even less than previous banks, which was not our intention. It is difficult for outsiders to understand the details of project operations, which is worth researchers investigating in depth.

Li Zexi: As an important participant in the bank's founding process, why didn't many of the ideas you mentioned materialize? Was it due to political interference, or did you not anticipate these issues at the time?

Batista: Establishing a global multilateral development bank is a formidable task, requiring "Chinese patience." When I moved to Shanghai in 2015, we had many goals, but after 10 years, many remain unfulfilled. For example, the current number of members is only 10 (5 founding + 5 new members), and Colombia's recent accession is a highlight, but it is still far from a true global bank.

Another goal is to conduct business in local currencies rather than just the U.S. dollar, which has seen some progress, but the NDB still mainly uses the U.S. dollar. The current president, former Brazilian president Dilma Rousseff, is working to promote local currency settlements and expand membership, and I hope she succeeds.

But the fact is, after 10 years, the bank still lacks transparency, many positions remain vacant, and the project operations are unclear, with too few members. Even with the 55% minimum proportion of founding members, we could certainly admit more small countries, but we haven't done so. Why? It needs investigation. I believe that in the next 10 years, we can do better than in the first 10 years.

Li Zexi: You mentioned that some reforms may be pushed, but obviously this will be very difficult, as it requires consensus among countries. Do you think this is still possible? Are there any ways to bypass this obstacle?

Batista: What kind of reforms would you recommend? Specifically what?

Li Zexi: For example, the 55% minimum ratio.

Batista: Reforming the Charter requires a procedure involving the approval of all member states (currently 10 countries), so it is a slow and difficult process. If we are going to take this route, I suggest carefully reviewing all the parts of the Charter that need to be modified and proposing them all at once, because the process is very difficult to advance, so it is better to present a comprehensive package. I hope this package can be well-designed, because honestly, apart from a few points, I think the Charter is successful. I remember when I was in Shanghai, the Charter did help me, it was clearly written.

Of course, there are also some aspects that can be criticized. The 55% minimum ratio you mentioned is indeed a pain point. But overall, the Charter is fine, and there is no need for major revisions. Our real problem is at the "constitutional level," that is, some institutional issues within the bank that cannot be solved even by reforming the Charter.

July 7, 2025, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Brazilian President Lula speaking at the press conference of the 17th BRICS Summit. Visual China

Li Zexi: Can you elaborate on what you think these problems should be resolved, and why they weren't resolved in the first ten years?

Batista: One is at the constitutional level, the Charter; the other is the rules and practices within the bank, which are not entirely dependent on the Charter. This is a complex issue. First, I don't quite understand why the BRICS countries didn't send the best talents to the bank. Many people appointed to management or other positions are not ideal. Because the New Development Bank needs people with both technical capabilities and geopolitical vision, who understand the purpose of creating the New Development Bank, not to replicate a World Bank or another traditional multilateral bank established by the West, but to create something different. But people with this understanding must also have strong technical capabilities. I'm not sure if the people we sent can meet both criteria.

I don't want to name names, but I basically think the bank's leadership lacks an understanding of the significance of the bank. It's not a routine matter, not an opportunity for people from Russia, China, India, Brazil, and South Africa to get high-paying jobs. It's an expensive bank, with substantial investments from member countries, so there must be results. To achieve this, we must appoint people with both technical capabilities and a firm geopolitical mission, which we have not done.

This also involves a more subtle and difficult-to-explain issue: the leadership of the bank has responsibilities, and the president and vice presidents must serve the institution itself, not represent their respective countries. This is very important, but it is often confused in practice. I've seen some vice presidents who completely see themselves as representatives of their home countries in the bank. This is actually illegal, but it has happened. The fact is, the NDB often does not follow its own governance rules.

I'm being straightforward now, we don't need to hide the issues or pretend they don't exist; we must face the shortcomings of the past decade to make progress in the next decade. I have confidence in the future. If you go to Shanghai, you can visit the NDB's beautiful building, which has about 100 employees and high prestige. Chinese state leaders recently visited the bank, which is unprecedented; President Dilma Rousseff also received the highest honor medal awarded by the Chinese government, which shows the Chinese government's respect for her and the bank she leads. So, the bank has great potential to become a very important institution in the next decade. I hope we won't let this potential down.

Li Zexi: I heard from other sources that the president and vice presidents are essentially representatives of their respective countries. For example, during the first term of President Dilma Rousseff, she essentially completed the term of the previous Brazilian candidate. The previous candidate was appointed by Bolsonaro. Later, when President Lula was elected, he replaced the previous candidate with Dilma Rousseff, becoming his own chosen president. This basically happened directly, and Rousseff didn't need anyone's approval to take office this year. If the opposition wins the Brazilian election next year, they may also appoint their own person. In this way, these positions are actually representatives of their respective countries, not the person selected by everyone. Do you think this is a problem? What do you think?

Batista: This is a problem. Let me explain. There is a difference between the law and the reality of politics. For example, according to the law, the IMF managing director and vice presidents should be officials of the fund, not representatives of their home countries. This is legally. What about politically? Politically, it is a customary rule that the IMF managing director is always from Europe, and the World Bank managing director is always from the United States. This is not accidental; the U.S. and Europeans are very clear about the significance of the nationality of the IMF managing director and the World Bank managing director. So they stick to this informal rule and will not change their minds. Legally, the management of the IMF and World Bank are not representatives of their home countries, but politically, if the IMF managing director is French, it makes sense for France; if the World Bank managing director is American, it makes sense for the United States; if the IMF vice president is Chinese, it makes sense for China.

It is the same with the New Development Bank (NDB) of the BRICS countries. When we drafted the Agreement, we also followed the same principle: the president and vice presidents are only responsible to the bank. But in practice, this principle was not strictly followed. Due to our lack of experience in handling such issues, some members of the management acted very rudely. For example, the Russian vice president has been in office for 10 years and was only replaced recently. His behavior within the bank was completely as an agent of the Russian government, without any disguise.

This phenomenon is partly because the NDB actually has no permanent board, so countries often see the vice presidents and presidents as representatives of their own countries, which violates the legal structure of the bank. The correct approach is that even if you are Russian, Chinese, Brazilian, Indian, or South African, it is acceptable to maintain close ties with your home government, but you must prioritize the interests of the institution you manage, consider the entire institution, not just its role for your own country. Building a senior bureaucracy that understands this subtlety is a challenge.

Again, take Brazil as an example. According to the rotation rules, from 2020 onwards, we had the right to appoint the second president of the bank. At that time, the ruling government was Bolsonaro's. Honestly, Bolsonaro's government was terrible—if you think Trump is a bad president, you would think Bolsonaro is worse, as he is a crude copy of Trump. Unexpectedly, Bolsonaro appointed someone completely unqualified as president, Marcos Troyjo. His performance was very poor, as he basically did not work at the bank, spending most of his time not in Shanghai, initially because of the pandemic, and later became a habit.

August 5, Brazilian far-right legislators protested the arrest of Bolsonaro, causing the legislative session to be suspended

In 2022, Lula won the election and took office in 2023. Upon learning of this issue, the Brazilian government conveyed its wish for Troyjo to resign and prepared a highly influential candidate: a former president of Brazil. When Brazil successfully convinced Troyjo to resign and appointed the former president to complete the remaining three years of the term, it immediately raised the international image of the NDB in an unprecedented way. This shows Brazil's importance to the New Development Bank: willing to send a former president to serve as president.

You just asked, what if the right-wing faction, Bolsonaro or his allies, win the election in 2026? It is indeed possible, and it would be a tough election. According to the original rules, Dilma Rousseff should have stepped down in July 2025, and it would be Russia's turn to appoint the president. But Russia proposed that she continue to serve. From what I know, this was not her initiative, but rather a request from Putin to Lula, which was a recognition of her work and possibly because a Russian president would severely harm the bank's interests under the current sanctions against Russia. I was surprised, and Lula and Rousseff probably were too. Regardless, she accepted to continue serving, but I'm not sure if she will stay for the full five years. If the Lula government is replaced by the right-wing in 2026 and the new government is hostile to her, I speculate she will resign, as it would make her work very difficult.

Therefore, I hope that if the right-wing, Trump-like forces win in Brazil in 2026 and Rousseff resigns, Russia can exercise its right to appoint a new president to complete the remaining term. After all, her term has five years left, and it's Russia's turn next.

Li Zexi: You mentioned earlier about the BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA), which is a mechanism where member central banks agree to pool their currencies into a common emergency liquidity fund. It is said that part of the negotiation was conducted in Australia. Can you elaborate on this story?

Batista: Yes, in 2014, Australia chaired the G20, and we were in the final stages of negotiations. At that time, representatives of the five BRICS countries frequently attended G20 and IMF meetings. So we used the opportunity to advance the CRA negotiations outside of G20 meetings in Washington, Melbourne, Sydney, etc. The key meeting that finalized the outstanding issues was held at a hotel where we stayed in Melbourne. At that time, we were busy with the CRA negotiations and had little time to attend G20 affairs. However, Australia had no role in the negotiations, it was just that we happened to be in Melbourne, so we took the opportunity to finalize the CRA.

Trump signing the "Genius Act"

Li Zexi: Finally, looking ahead, there was also a news item recently, stating that the U.S. plans to use stablecoins to maintain the dominance of the U.S. dollar, which Trump calls the "Genius Act." However, one of the initial intentions of cryptocurrencies was to replace existing currencies and weaken the control of national governments over their own currencies. What role do you think cryptocurrencies will play in the discussion on "de-dollarization"?

Batista: I don't think private institutions issuing cryptocurrencies can play a substantive role in this regard. The one that could potentially drive de-dollarization is central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). This is different from private cryptocurrencies, as they are issued by central banks in a digital form and can serve as a means of payment and reserve asset. Currently, China, Brazil, Russia, and India are all developing CBDCs. We need to integrate these CBDCs and include them in a unified payment system and reserve system, ultimately creating a new reserve currency; this is what Americans fear the most.

Trump is tough on this, but the problem is that America's biggest enemy is not the BRICS, but itself. The U.S. abuses the status of the U.S. dollar as a reserve currency, using it to implement various sanctions, freeze other countries' reserves, and conduct extraterritorial jurisdiction, leading to serious damage to the trust in the U.S. dollar.

Last year, I attended a meeting in Russia, and finally, President Putin concluded the speech and answered questions. I asked him: Mr. President, what do you think the role of the BRICS in de-dollarization is? He calmly and without irony replied: "Wait, we are not against the dollar, it is the dollar that is against us." This statement was very accurate.

If the dollar could be managed neutrally, we wouldn't even need to discuss de-dollarization. Of course, digital currencies will play a role, but not the kind of cryptocurrency proposed by the U.S. House of Representatives. U.S. economist and former IMF Chief Economist Simon Johnson wrote a good article pointing out that the way the U.S. is currently preparing for cryptocurrencies is a "recipe" for financial crises, instability, and money laundering, unrelated to the discussion on de-dollarization. This is more like a scam, another self-inflicted trouble for the U.S. The correct path to establish a new system can only be coordinated actions by central banks of various countries.

Li Zexi: Thank you very much for accepting the interview from PacificPolarity, Paulo. We have gained a lot of knowledge about the different operating methods of the BRICS and the IMF, as well as your behind-the-scenes experiences in the two institutions.

Batista: Thank you for inviting me, I'm glad to have this conversation with you.

This article is an exclusive article from Guancha.cn. The content of the article is purely the personal opinion of the author and does not represent the view of the platform. Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited, otherwise legal responsibility will be pursued. Follow Guancha.cn on WeChat (guanchacn) to read interesting articles every day.

Original: https://www.toutiao.com/article/7540083818552656438/

Statement: This article represents the personal views of the author. Please express your attitude by clicking the [top] or [bottom] button below.