There are 5282 characters in this article

It is expected to take 12 minutes to read

Author | Ajay Chhibber, Translator | Zhu Yilin, Reviewer | Zhang Qian, Editor of this issue | Jiang Xinyu

Reviewer of this issue | Jiang Yi

Editor's Note

This article argues that India is at a critical stage of its demographic dividend, which is both a historical opportunity and a real challenge. However, due to multiple structural problems currently faced, there is a risk that this potential advantage may transform into a heavy burden. First, there is a lack of employment opportunities. Although the service industry, such as information technology, has developed rapidly, it mainly absorbs a small number of high-skilled talents, unable to provide sufficient jobs for the majority of low-skilled laborers, resulting in a large population remaining in rural areas or trapped in the informal sector in cities with low wages. Second, the industrialization strategy has defects. The government expects to promote manufacturing development through the "Production Linked Incentive Scheme" and support for leading enterprises, but this model has obvious shortcomings. Additionally, high energy, transportation, and financing costs, as well as complicated labor regulations, restrict the expansion and competitiveness of the manufacturing sector. Third, the agricultural crisis is prominent. Although agriculture contributes about 15% of GDP, it still supports 42% of the population, contradicting the trend of labor transfer predicted by Lewis' turning point theory. Farm sizes continue to shrink, productivity is low, and modernization reforms are seriously lagging. Fourth, urban governance capabilities are insufficient. Village councils and local governments in cities generally have weak administrative efficiency and financial capacity, making it difficult to support smart and efficient urbanization. Overall, if India does not achieve structural reforms and form a virtuous cycle between agricultural transformation, manufacturing revitalization, and urbanization, its demographic dividend will not only be difficult to convert into a growth advantage but may also become a heavy social and economic burden. South Asia Research Communications has translated this article for readers to critically reference.

On February 7, 2019, job seekers filled out application forms at a recruitment event in Chinchwad, Maharashtra, while others queued for registration. Photo credit: DANISH SIDDIQUI / Reuters

If effective employment creation and in-depth structural reforms cannot be achieved, India's once-in-a-century development opportunity could potentially turn into a heavy long-term burden.

India entered the so-called demographic dividend phase around 2005, which is expected to last until 2055. The demographic dividend refers to a period when the proportion of the working-age population (aged 15–64) is relatively high, thus enabling economic support for both the elderly and the young. So far, India has used nearly two-fifths of its demographic dividend period—India's population experienced explosive growth between 2003 and 2012 and again between 2021 and 2023—but has failed to achieve sustained economic growth. Since 2010, the impact of economic growth on employment has been gradually weakening.

Japan, Hong Kong, and Singapore entered the demographic dividend period in the 1960s and quickly developed into developed countries. China entered the demographic dividend period during its economic reforms in the 1980s and subsequently achieved over three decades of sustained high-speed growth. Brazil entered the demographic dividend period in the 1960s and experienced a brief period of rapid growth between 1966 and 1975, but failed to maintain this momentum. The Arab world entered the demographic dividend period in the 1990s, but due to a lack of economic growth and employment opportunities, especially for educated youth who felt frustrated, it led to the "Arab Spring" a decade ago, transforming the demographic dividend into a demographic disaster.

The working-age population in India is expected to increase by at least 12 million annually before 2030, equivalent to adding the population of Belgium each year. To effectively absorb surplus labor and reach the Lewis turning point (Editor's note: The Lewis turning point refers to the turning point where labor moves from excess to scarcity. In the process of industrialization, as surplus rural labor gradually shifts to non-agricultural industries, the surplus labor decreases and becomes scarce, eventually reaching a bottleneck state), India needs to create at least 8.5 to 9 million jobs annually.

This means that to achieve the demographic dividend and create enough employment opportunities, India needs to maintain an annual economic growth rate of at least 12%. For an economy that had already slowed down to 4% to 5% before the pandemic, achieving this goal is undoubtedly a great challenge. Achieving an annual GDP growth of 8% to 9% (which India reached between 2003-2008 and after the pandemic between 2021-2024) is already considered a significant achievement. Therefore, India must promote more inclusive growth and drive more employment through economic growth: every 1 percentage point of GDP growth should create at least 1 million jobs.

China and Vietnam in recent years have created a large number of employment opportunities through manufacturing, transferring a large population from the agricultural sector, thus achieving structural transformation in the sense of Lewis, improving people's living standards, and reducing poverty. In contrast, the prosperity of India's service industry has created some employment opportunities, but a large number of unskilled laborers remain stuck in rural areas or flood into cities to engage in street trading or construction work, often earning below the poverty line.

In other words, although India has become a global IT outsourcing center, low-skilled workers have not truly benefited from the development dividends. A small number of skilled workers have found employment in the rapidly developing IT and service sectors, while a large number of unskilled laborers remain underemployed or self-employed in poverty, forming a dual structure largely due to India missing the opportunity for industrial development, contrasting sharply with China. Today, Vietnam is following China's developmental path.

Some experts believe that India should continue to consolidate its existing advantages in the service sector and need not attempt to revitalize its industrial sector. However, in the current environment of frequent trade friction, the possibility of success for an export-oriented growth strategy is relatively limited. India's share in global industrial exports has dropped to about 2.4%, and even if it doubles, it would still be unlikely to pose a substantial challenge to other countries. At the same time, India must realize that no country can achieve economic development solely based on its domestic market, even if global markets face tariff barriers and trade restrictions. For India's current GDP of about $4 trillion, its domestic market is still insufficient compared to the global market of over $100 trillion. Furthermore, if India can enhance its competitiveness, it may still have the potential to become an alternative option in the "China +1" strategy (Editor's note: The "China +1" strategy refers to a supply chain diversification strategy where companies establish operations or procurement outside of China while maintaining their business in China. This approach allows companies to diversify their supply chains and reduce dependence on a single country).

The government naturally has not abandoned the industrialization process. However, its new industrial strategy, which provides import protection and subsidies to 14 industries through a 25 billion USD production-linked incentive program (PLI), may not be the optimal solution.

Reintroducing import protection policies not only means returning to an era of high prices and low quality, but also hinders India's integration into global and regional value chains, which are the core of modern trade. Under the support of the production-linked incentive program, India has made certain achievements in iPhone manufacturing, but overall, whether this success can be replicated in other fields remains unclear; even in the iPhone manufacturing field, the Trump administration once threatened Apple not to conduct manufacturing in India.

More fundamentally, we must analyze why revitalizing Indian industry requires the production-linked incentive program. The reason is that the cost of doing business remains high. Although infrastructure has improved, the usage cost is still high. The price of gasoline in India is 50% higher than in China and other competing countries, and the price of diesel is 20% higher due to government taxes. Indian railway freight charges are three times those of China, the highest in the world. The cost of electricity for production enterprises is 30% to 40% higher than in China and other main competing countries. Although the interest rate for capital lending has decreased, it is still higher than in China and major Asian competitors.

On September 17, 2023, members of the Youth Congress in India held a symbolic protest in New Delhi against the increasingly severe unemployment problem. Photo credit: SHIV KUMAR PUSHPAKAR

Additionally, labor laws stipulate that for enterprises with more than 10 employees, the hiring process is extremely cumbersome, which makes India's labor-intensive manufacturing less attractive. As a result, the industrial sector tends to adopt a capital-intensive model or hire daily workers to engage in low-productivity activities to avoid regulations. India has the highest proportion of temporary wage workers, accounting for about one-third of the total labor force, higher than Pakistan (17%), Nepal (10%), Bangladesh (22%), Afghanistan (14%), and Bhutan (4%). Sri Lanka and the Maldives almost have no such workers.

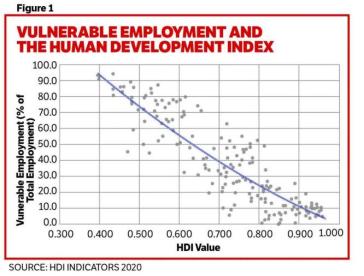

Figure 1 Source: HDI IDICATORS 2020

The Lewis model predicts that as the country develops, more people will enter the organized sector. However, most of India's employment remains concentrated in the informal sector. The share of vulnerable employment, including agriculture, should not exceed 50%, but in reality, it exceeds 75%, much higher than Bangladesh (see Figure 1).

Therefore, most of India's labor force lacks social security. This issue was fully evident during the sudden lockdowns during the pandemic: millions of temporary workers were forced to walk back to their hometowns under harsh conditions, forming the largest population migration in India since independence.

Land, India's most scarce resource, is inefficiently utilized and costly to obtain. More than 40% of the labor population remains in the agricultural sector, with nearly 70% engaged in marginal farming (Editor's note: Marginal farms refer to farms operated on small or low-yield land, usually with poor natural conditions and weak infrastructure, making them difficult to profit). This leads to inefficient use of land. India's building floor area ratio (Editor's note: The building floor area ratio refers to the ratio of the total floor area of all buildings above ground to the base area) ranks among the lowest globally, resulting in slow urban expansion.

Indian industry is showing increasing concentration, with the five major corporate groups (Reliance, Tata Group, Adani Group, Aditya Birla Group, Bharti Airtel) not only dominating the overall industrial system but also squeezing the development space of the next five groups and the top twenty groups. If India attempts to cultivate "national champions" by supporting large enterprises, imitating the Asian industrial policy model (such as South Korea's chaebols), it must recognize that South Korean chaebols, while benefiting from policy advantages, are also subject to export-oriented trade constraints. In recent years, India has significantly increased tariff protection, and the scale of the five major corporate groups has expanded faster, but primarily focused on the domestic market rather than global exports.

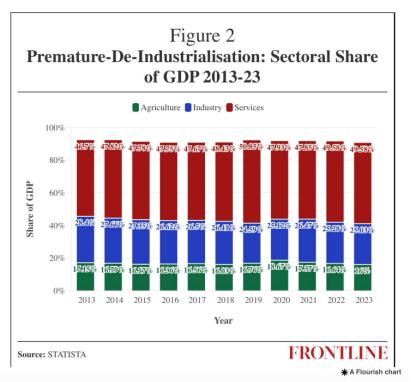

If India hopes to rely on large enterprises, provide massive subsidies and tariff protection to cultivate world-class companies to lead industrial development, this strategy seems to have not achieved the expected results. In fact, its effects may be counterproductive. As the Turkish-American economist Dani Rodrik pointed out, we are experiencing "premature de-industrialization" (see Figure 2). Rodrik warned many years ago that many developing countries prematurely shifted to the service sector before completing the industrialization process, thereby missing the productivity gains and large-scale employment opportunities traditionally brought by manufacturing.

Figure 2 Source: STATISTA

Information technology services, healthcare, and e-commerce are less affected by the aforementioned factors, so they have developed relatively quickly. However, the back-office outsourcing businesses driven by information technology growth, and the approximately 2,000 global capability centers (GCCs) that have created nearly 1.5 million jobs, may face potential threats from artificial intelligence in the future. Despite this, India should continue to develop, address the challenges posed by artificial intelligence, and leverage its leading "data stack" (digital stack) to foster new startups, while encouraging the development of labor-intensive service industries such as tourism. However, these areas can only benefit about 5% of the workforce, not creating millions of jobs sufficient to help the population with basic education transition from agriculture to basic industrial positions. Therefore, the issue is not a "battle between industry and services," but rather that industry and services must both thrive for India to succeed. We need to solve the fundamental issues that determine the cost of doing business, rather than relying on temporary measures such as the production-linked incentive program.

India must also address the problems facing the agricultural sector, which supports most of the population. Currently, agriculture contributes about 15% of GDP, but 42% of the population still depends on agricultural employment, compared to about 10% in China and less than 1% in the United States. Contrary to what the Lewis transformation theory predicted, the number of people dependent on agriculture in India has not decreased but has increased since 2018 and 2019.

Before that, according to a study titled "Report on the Condition of Farmers in India" by CSDS-Lokniti in 2018, nearly 61% of the interviewed farmers stated that if they could find work in the city, they would give up farming. According to agricultural census data, the average size of Indian farms has shrunk by more than half in 45 years up to 2016, from 2.28 hectares to 1.08 hectares. Moreover, out of the total 146 million farms, nearly 100 million are marginal farms with an area of less than 1 hectare.

Among the 42% of the population dependent on agriculture, more than half have no land and can only work as agricultural laborers because they have no other jobs available. The CSDS-Lokniti study showed that only 26% of farmers are willing to continue farming. They prefer direct income support deposited into bank accounts rather than relying on input subsidies. Only 8% of farmers believe their problem stems from low crop prices, while nearly 50% of farmers believe their problems relate to low productivity, inadequate irrigation, and poorly structured agricultural systems.

Currently, agriculture contributes about 15% of India's GDP, but 42% of the population still depends on it, compared to about 10% in China. The photo shows cotton farmers in Hyderabad, India, on March 2, 2017. Photo credit: Getty Images

However, India has introduced a series of inefficient subsidy programs to help farmers, with funds allocated for employment guarantee schemes exceeding investments in improving irrigation, roads, electricity, and R&D, which enhance productivity.

The problems troubling Indian farmers go beyond how to transfer labor from the agricultural sector, but also how to achieve a leap in productivity, optimize crop structures to produce more marketable and price-competitive agricultural products, significantly improve the marketing chain from farm to table, enhance the ability to cope with climate change, and establish new mechanisms to reduce risks and uncertainties. One of India's most respected agricultural experts, Sardara Singh Johl, has called for a "Second Green Revolution" in India for the past 30 years.

Furthermore, how India can wisely and efficiently advance urbanization is equally crucial. As the third-tier government in India, village councils (panchayats) and urban local bodies are weak in both governance capabilities and financial strength. Municipal fiscal issues require urgent attention, especially low property taxes and low usage fees. India must increase the building floor area ratio to avoid urban sprawl and inefficient urbanization.

If India hopes to achieve a 7% to 8% economic growth, its urban development—how to achieve agglomeration benefits, absorb new populations, and grow into innovation centers, rather than becoming hubs of conflict, crime, pollution, poor hygiene, and traffic congestion—depends on India's ability to actively and wisely address these challenges.

The core focus of this article is on the economic structural transformation required for India to realize its demographic dividend. As we discussed in our co-authored book "Unlocking India," India must also promote government reforms and improve its education and healthcare systems to achieve "Prosperous India" (Samrudha Bharat) and "Inclusive India" (Sajit Bharat). There is no doubt that India's GDP will rise to the third-largest economy in the world by 2030, but to make the economy truly follow the right path and achieve "Developed India" (Viksit Bharat), profound and radical strategic adjustments are still needed.

About the Author: Ajay Chhibber is a distinguished visiting scholar at the Institute for International Economic Policy at George Washington University.

This article is translated from an article titled "The clock is ticking on India’s demographic dividend" published in Frontline on August 6, 2025. Original link:

https://frontline.thehindu.com/economy/india-demographic-dividend-unemployment-crisis-agriculture/article69873237.ece

Editor of this issue: Jiang Xinyu

Reviewer of this issue: Jiang Yi

* Send "translation" to the official account's backend to view the previous translation collections.

We welcome your valuable comments or suggestions in the comment section, but please keep them friendly and respectful. Any comments with offensive or insulting language (e.g., "A3") will not be accepted.

Original: https://www.toutiao.com/article/7559260596387824155/

Declaration: This article represents the views of the author and welcomes you to express your attitude in the 【Top/Down】 buttons below.