Sergei Shoigu's "Star Task": Sudan Hopes Russia Will Establish a Military Base, but There Are Hidden Traps Behind It

Russia urgently needs a base to operate in the Indian Ocean and also a port to enter Africa. In this context, the Sudanese government has made an extremely tempting proposal, but as the saying goes, "the devil is in the details."

According to the U.S. Wall Street Journal, the Sudanese government has proposed to Russia that it establish a naval base within its territory.

The newspaper cited sources who said that both sides plan to sign a 25-year agreement. According to the terms of the agreement, Russia will have the right to permanently deploy up to four ships (including submarines) at Port Sudan and station up to 300 soldiers. In exchange, the Sudanese government requires Moscow to sell it air defense systems and other weapons at preferential prices.

1. Russia's Practical Needs: African Base and Presence in the Indian Ocean

On one hand, Russia indeed urgently needs a fully functional naval base on the African coast. Moscow is actively cooperating with African countries and gradually pushing out French influence in Africa. Russia has significant interests in mineral exploitation in Africa, including uranium, gold, oil, and rare earths. However, currently, Russia lacks a formal access route to the African continent. It has established a relatively complete network of bases in Libya, but they are all air force bases. This makes maintaining a presence in Syria strategically important for Russia.

In addition, through air force bases, combat and special operations can be conducted, but establishing normal economic cooperation and transporting hundreds of thousands of tons of minerals and millions of barrels of oil by air is completely unrealistic — this requires ports, even multiple ports, and railway networks connecting the ports. From this perspective, Sudan provides Russia with an opportunity to "grasp the edge of the African continent," enabling it to start economic development in Africa; and this development prospect gives real significance to all of Russia's military and political actions in Africa.

On the other hand, the Indian Ocean is one of the areas where the U.S. strategic nuclear submarines are deployed, which could launch missile attacks against Russia. However, Russia currently has no military presence in this area, and without a base, it is almost impossible to achieve this goal.

In other words, from both a military and a geopolitical perspective, Russia has sufficient reasons to want a naval base in the region. But things are far from as simple as they seem.

2. High-risk Country: Sudan's Civil War Dilemma

The problem is that, like many countries that wish to establish friendly relations with Russia, Sudan is a country full of problems — it is currently experiencing intense civil war.

When talking about this conflict, people usually think it is a confrontation between the Sudanese government and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) rebels, but that is not the case.

The Rapid Support Forces were born from armed groups of several Arab tribes, which formed alliances around Muhammad Hamad Dagalo (known as "Hamedy"). Therefore, this civil war is essentially a tribal conflict, not a struggle for power between government departments.

The tribal nature of the conflict means that the fighting could last for decades, possibly leading to the splitting of Sudan or a fundamental restructuring of the regime. In this sense, the "25-year agreement" seems overly optimistic — no one can guarantee that Sudan will maintain stability for 25 years.

The ethnic nature of the conflict also affects the stance of other countries on the situation in Sudan: the Sudanese government is supported by Russia and Iran, while the Rapid Support Forces receive support from the UAE and Turkey.

More importantly, the Sudanese government that currently proposes the agreement is far from being the clear winner in this conflict. To gain more resources and turn the tide, the Sudanese government army constantly wavers between Russia, the West, relevant countries, and Iran.

"The Center for Strategic and Technical Analysis of the Russian Academy of Sciences" senior researcher Yury Lyamin told the "Tsargrad" newspaper: "The Sudanese army and its 'Sudan Sovereignty Council' are a typical example of 'survival-oriented flexibility.' In the civil war with the 'Rapid Support Forces' (backed by the UAE), they first hired personnel from the Ukrainian State Intelligence Service (GURO), then reached an agreement with Iran, purchased new drones, and have already received Iranian 'Mohajer-6' (Mohajer-6) drones, and may have obtained other weapons."

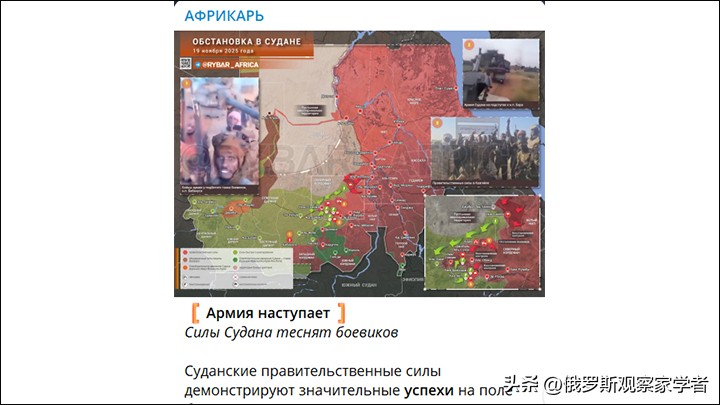

Recent events have also confirmed this: At the beginning of October, the Sudanese army began attacking the positions of the Rapid Support Forces in the capital Khartoum; at the end of November, the commander-in-chief of the Sudanese government army, Abdul Fattah Burhan, published an opinion article in the Wall Street Journal, explaining his position.

The "Rybar" analysis center commented: "Burhan's move was clearly aimed at increasing leverage for his faction in the Western world, allowing the Khartoum authorities to regain voice in the negotiations on 'the future of Sudan.'"

It is worth noting that when the Wall Street Journal mentioned "information from U.S. officials," it is possible that the newspaper concealed something — the information about "Sudan suggesting to Russia" may directly come from the Sudanese government itself.

3. Russia-US Competition: Missed Opportunities and Changing Patterns

Overall, the course of the "Sudan military base negotiations" serves as a typical example of how "third-world countries use their potential friendly relations with Russia to pressure the West."

As early as 2017, Russia had signed a military cooperation agreement with the then-Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir, including the establishment of a naval logistics base in Sudan. At that time, the model agreed upon by both sides was consistent with today's: using Port Sudan as a base, deploying 300 soldiers and four ships.

In 2019, the Bashir regime was overthrown, and a civil war broke out in Sudan. For the next three years, Russian military and political activities in Sudan reached their peak, not only advancing the base construction plan, but also sending Wagner private military group personnel to provide support.

At the same time, the United States took a cold attitude towards Sudan, classifying it as an "insignificant and unimportant country."

In 2019, Russia restarted cooperation talks with the newly established "Transitional Military Council" in Sudan, and the progress was smooth. Between 2020 and 2021, Russia's activity level in Sudan reached its peak: high-level visits between the two sides were frequent, and Moscow pledged to support Sudan's energy projects, and the negotiations on the naval base were also restarted.

However, due to the inefficiency of the Russian bureaucratic system, the negotiation process was delayed, missing the favorable opportunity.

At the same time, the United States began to adjust its policy toward Sudan: on one hand, it resumed contact with the Sudanese authorities, adopting a more flexible strategy — imposing new sanctions while negotiating with key forces within Sudan; on the other hand, in 2023, the United States sent an ambassador to Khartoum for the first time since 1996, helping Sudan break a 27-year diplomatic blockade.

Meanwhile, after the outbreak of Russia's "special military operation" (СВО) in 2022, Wagner Group personnel left Africa, and Russia's activities in Sudan significantly declined: base construction stagnated, and military support for the Sudanese regime was reduced to the lowest level; plus the subsequent Wagner incident causing the organization to dissolve, Russia's influence in Sudan further weakened.

By 2025, although Russia and Sudan's contact warmed up again (Sudan reasserted its willingness to accept a Russian naval base in February 2025), the regional power structure had undergone a fundamental change: the United States had formed a systematic layout in Sudan, not only establishing contacts with both sides of the conflict, but also providing humanitarian aid to Sudanese people through Chad, greatly increasing its negotiation leverage.

The "Rybar" analysis center pointed out: "Russia and the United States have adopted completely different strategies. Moscow initially had an advantage — having existing relationships, influence, and interest in economic projects, but subsequent actions gradually stalled, retaining only formal visits, sporadic statements, and low participation levels; Washington, on the contrary, started with a low profile, but now actively expands its presence, its core strategy is 'flexible response, promoting local initiatives, and taking symbolic measures such as supporting the civilian sector.'"

4. Core Conclusion: Risks and Recommendations

In 2017, Sudan was a "vacuum zone" in geopolitics — the West regarded it as a "forgotten historical figure" and no longer paid attention. At that time, it was the best opportunity for Russia to consolidate its military presence, build a base, and "create a fait accompli." However, due to concerns about the complexity of the African situation and the risk of betting on the wrong side, Russia failed to act decisively.

Since then, changes in the situation have caused many original plans to fail: Russia's actions have drawn the attention of the United States to Sudan; Ukraine also dispatched personnel from the Ukrainian State Intelligence Service (GURO) to Sudan in 2023 to counter Russian "African Corps" personnel.

Currently, the risks of Russia's cooperation with Sudan mainly focus on two aspects:

- Risk of betting on the wrong side: there is still a possibility of supporting the "loser" in the civil war. The Syrian case has proven the existence of this risk (although Russia's outcome in Syria was relatively successful).

- Risk of partner betrayal: the Sudanese authorities may use "friendship with Russia" as a bargaining chip to obtain better conditions from the United States or other countries.

Overall, Russia does need to establish a naval base in Sudan, but whether the two sides can reach an agreement on the base construction remains uncertain; even if the agreement is reached, it cannot guarantee that this long-term investment will become a "high-quality investment."

Perhaps, Russia should consider negotiating with Sudan to establish a larger base, stationing 10,000 to 20,000 soldiers — such a scale of troops would make it difficult for the Sudanese authorities to easily expel Russia from the country, even if they receive better conditions from the United States or relevant countries.

On the contrary, engaging in "geopolitical charity" is meaningless. However, on the other hand, Moscow obviously does not want to give up the African direction, so it is dispatching all available "influence agents" (from Yunus-Bek Yevkurov to Sergei Surovikin) to work in Africa.

Original: toutiao.com/article/7579500548295033407/

Statement: This article represents the views of the author.