Recently, the Trump administration appointed Nick Adams, a right-wing internet celebrity known for his pro-Israel comments, as the next U.S. ambassador to Malaysia, which has sparked significant controversy in this Muslim-majority country. Political analyst Bridget Welsh, who focuses on Southeast Asian issues, said that by doing so, the U.S. might "push all Southeast Asian countries into China's arms."

Welsh's concerns are not unfounded. In a podcast episode titled "Pacific Polarity," Evan Feigenbaum, a U.S. policy expert at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, stated that due to the U.S. policy in Asia focusing on security concerns against China rather than the needs of regional countries, the U.S. influence will gradually fade from the region within a decade.

Evan Feigenbaum is the Vice President for Research at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. He previously held several senior positions at the U.S. Department of State, including Deputy Assistant Secretary for South Asian Affairs and Deputy Assistant Secretary for Central Asian Affairs, focusing on East Asian and Pacific region affairs. After leaving government service, he has been working in the think tank field.

The content of the speech was compiled and published by Observers, for the reference of readers.

Translated by: Li Zexi

Richard Gray: In this episode of "Pacific Polarity," we invited Dr. Evan A. Feigenbaum. Your doctoral research focused on Chinese politics. Subsequently, your career expanded to East Asia, South Asia, and Central Asia, where you held relevant positions in both the public and private sectors. Given the current high attention on China in the U.S., what prompted you to broaden your focus to the entire Asia, a region encompassing about half of the world's population? Do you see a coherent thread connecting different sub-regions of Asia?

Evan Feigenbaum: My initial career path followed a very traditional "China expert" route. I earned a doctorate in Chinese politics, wrote a book on China, and taught courses on China-related topics. Then, I joined the government, during which time I began taking on roles involving other parts of Asia.

I sometimes joke that my career trajectory mirrors that of Genghis Khan - sweeping from one part of Asia to another - of course, I didn't conquer any places along the way, but I did get involved in multiple regions.

The most interesting aspect was the timing. As you said, this all happened in the first decade of the 2000s. It was a period when various sub-regions of Asia were re-achieving economic, financial, and to some extent strategic integration, resembling more the natural structure of Asian history than what I sometimes call the "Cold War anomaly."

Taking Central Asia as an example. During the periods when it was part of the Soviet Union and the Russian Empire, many of the original natural connections in Asia - through trade routes, religious dissemination, and the exchange of ideas - disappeared. The same goes for the relationship between India and East Asia. Many of the place names we use today reflect the historical legacy of India in East Asia, such as "Indonesia," "Indochina," and Cambodia still has Hindu temples, which are traces of history. However, under the British colonial system, the broader and more natural links between India and the region were artificially severed.

Evan Feigenbaum (Photo) Carnegie Endowment for International Peace website

Therefore, just as my personal and professional trajectory shifted from a singular focus on China to a broader role and responsibility across Asia, the region itself was also undergoing not just a transformation, but a kind of "historical return."

For example, in Central Asia, China is now the largest trading and investment partner for most countries. Although the context today is different, this reflects in a way the historical role China played in Central Asia before the Russian era. There is now a large amount of Asian capital flowing within Asia, seeking investment returns, which was unthinkable when I first started my career two decades ago. So, from this perspective, I believe Asia is returning to some historical patterns and norms - those that are more natural and defined the evolution of the Asian region, but were interrupted by some artificial political, strategic, and institutional structures later on.

There is a question worth serious discussion: Is the U.S. ready to deal with a "more Asian, less Pacific, more integrated" region? If you know my research, you'll know that my general answer to this question is no: the U.S. is far from ready.

Therefore, I believe that Asia will be very different from what I saw when I first entered the field in the 1990s.

Richard Gray: In 2009, you and Robert Manning co-authored a special report for the Council on Foreign Relations titled "The United States in the New Asia." Looking back at this report, it is particularly notable that the U.S. approach today is almost exactly the opposite of what you proposed, or only a small part of your recommendations have been adopted, and their effects are minimal and have largely disappeared. You emphasized the importance of participating in multilateral dialogues, but both Democratic and Republican administrations have performed poorly in terms of sustained participation. Even today, I'm still not clear about the U.S. vision for cooperation with ASEAN, despite the fact that it has been many years since the establishment of this cooperation.

Even though the Biden administration has adopted a "latticework approach" to building alliances, not all frameworks include the U.S., and the content is extremely biased towards security, ignoring some key economic elements; even these security pillars themselves have a lot of uncertainty about their future direction. These complex issues between security, economic, and institutional elements - what's the problem? Quoting your words - are we really becoming the "Hessians" of Asia today?

Evan Feigenbaum: First, I think it's necessary to take a step back and raise this question: What makes the U.S. a leader in this world region? If we project ten years ahead, will the pillars that support U.S. leadership be the same as fifteen or twenty years ago, or even during the Cold War?

In another article I co-wrote with Robert Manning in 2012 titled "A Tale of Two Asias," I mentioned that the reason the U.S. has long played a leading role in Asia is not only because it is a security provider, but also because it provides a lot of public goods and benefits related to the economy for the region.

In the security domain, the U.S. has basically maintained peace. Whether it's its allies or countries that are not allies but benefit from the security provided by the U.S. (through alliance mechanisms, overseas garrisons, aircraft carrier battle groups, etc.), this security role provides a kind of "security blanket," allowing all countries except China and North Korea to pursue their own goals, including development, growth, and prosperity, under this protection.

This leads to the second pillar. The reason the U.S. is a leader in the region is not only because it is a security provider, but also because it is an important economic leader. It is the demand from the U.S. market that supports the export-oriented development path of Asian economies. The U.S. has also always been a rule-maker, a standard-setter, and a promoter of norms.

This is the traditional role. Today, we must step back and ask: Are the U.S. policies and postures still playing the existing security role and also the economic role? In the first question - the security domain - my answer is, to a large extent, yes. Because most countries are afraid of China and still hope the U.S. exists in the region.

But in the economic domain, if you look ahead ten, fifteen, or twenty years, the economic pillar of U.S. leadership may weaken relatively, although the U.S. will still play an important role in absolute terms. The trade volume between the U.S. and all countries in the region is increasing in absolute terms, but in relative terms - i.e., as a percentage of each country's total trade - it is generally declining. Look at the difference in China's position in Asia 25 years ago and today to understand this.

Moreover, in the past few administrations, especially under this administration, the U.S. is increasingly seen as closing its market, raising barriers, and being unwilling to participate in agreements that set rules or standards. This is a completely different configuration of U.S. power. And this means that Asian countries themselves will increasingly tend to set their own rules without U.S. involvement.

On January 23, 2017, then-U.S. President Trump signed an executive order deciding to withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Reuters

First, we must realize that this situation is completely different from the Cold War or the early post-Cold War era. Second, there is another issue - this is exactly what Robert and I raised in our Council on Foreign Relations report: Is the U.S. adapting to this change? In other words, if Asian countries start setting rules on their own, is the U.S. willing and necessary to join in? If institutions, agreements, and consensus are formed exclusively among Asian countries, what role would the U.S. play? For example, the U.S. is outside of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP); the U.S. is outside of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP); the U.S. is outside of the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA).

This creates a trend: the process of rule-making in Asia is happening, and the U.S. is either looking in through a glass or actively stepping back. This brings up a major issue - how does the U.S. want to position itself?

Finally, I want to say that this means the U.S. is facing a confidence crisis - regarding what role it can actually play, what role it is willing to play, and ultimately what role it will play, and how Asian countries should adjust their positioning accordingly. This is not the first time the U.S. has faced a confidence crisis in the region. For example, after the failure of the Vietnam War in 1975, many people questioned whether the U.S. could maintain its presence in the region. But I think this moment is especially important, because the current Trump administration has taken positions on a series of issues highly concerned by Asian countries - enterprises, markets, populations, trade, tariffs, protectionism, trade conditions, etc. - which have caused widespread concern, and people don't know what role the U.S. will play.

So I would say that the U.S. hasn't adapted well to this change. This is exactly what Robert and I emphasized in that report: the U.S. needs to prepare for a more "Asian" era, and cannot assume it is at the center anymore. And I think that this self-centered assumption is still deeply rooted in Washington - people think that as long as Asian countries are afraid of China, the U.S. can always be the "alpha and omega" of the region. I'm sorry, but this view is unrealistic.

"To get China policy right, you must first get Asia policy right," the U.S. has completely inverted this view

Li Zexi: Recently, at an event hosted by the Lowy Institute, John Hamre, CEO of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), pointed out that due to the chaos at the top, Elbridge Colby, the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy in this administration, has gained unusual power. Hamre also described Colby as "a person with an unusually single-minded focus on fighting China."

At the same time, his superior Pete Hegseth, in his speech at the Shangri-La Dialogue, also focused on competition with China and called everyone present in the audience "allies and partners" in this endeavor. As you said, this almost makes one feel that the U.S. entire Asia policy has been reduced to China policy. This trend obviously goes beyond the current Trump administration, and is a more long-term phenomenon.

However, China is indeed becoming more powerful and influential, which has undoubtedly amplified the voices within Washington advocating for this "China-focused" strategy. So, can this trend be changed? Or should it be changed?

Evan Feigenbaum: If the U.S. wants to remain relevant in Asia, it must respond to the goals and demands of Asian countries themselves. The reality is, first, most Asian countries do not want to decouple from China; second, they simply do not have the luxury of decoupling, because their core concerns are: growth, employment, sustainable development, and skill enhancement. In these areas, the opportunities China provides in the region, no Asian country is prepared to completely reject.

If the U.S. keeps spreading the message throughout the region that "remove China from the Asian story," "don't take Chinese money," "don't use Chinese technology," it will be hard to gain support. Everyone says the U.S. needs a competitive proposal, but the issue is not just "competition," but the U.S. must set the framework and background of the competition together with Asian partners, thereby influencing how China interacts in the region.

A former boss of mine at the State Department, Richard Armitage, recently passed away. He was my deputy undersecretary and a seasoned Japan expert and Asia expert. He once famously said, "To get China policy right, you must first get Asia policy right." I think what he meant is that the U.S. cannot always directly influence China's choices. However, if it can shape the strategic environment in which China operates together with its partners, it can at least influence the incentives and constraints China faces when making its own policy decisions.

And your previous question is essentially pointing out that the U.S. has completely inverted Armitage's view - instead of "getting Asia policy right to get China policy right," it has become "all Asia policy is derived from China policy." And this trend has spanned several administrations of both parties.

But the problem is that this "China-centric" perspective is not the one most Asian countries认同.

Secondly, the way the U.S. handles this competition is completely securitized. Everything is seen as a national security issue - technology, cultural exchanges, economic flows, Chinese investments, etc. Americans see it this way, but this is not necessarily how Malaysians see it, let alone how Vietnamese people see it - even though Vietnam has had conflicting feelings toward China. This attitude is difficult to resonate with in the region; worse still, it weakens the attractive proposals the U.S. should put forward to the region.

So, can this trend be adjusted again? You asked that earlier. I am not sure, because I think we have formed a deep-rooted political and bipartisan consensus trajectory, which has been integrated into the U.S. political system - the one you mentioned, the "China-focused security competition," and trying to force the U.S. strategy for the entire region into this framework.

This is precisely why the U.S. has difficulty gaining the influence it needs and should have among Quad member states. There is a huge disconnect between the Quad narrative and the narratives of most other countries in the region. Perhaps the Philippines is an exception, but you know that the Philippines changes its government every six years almost like a new country, so we cannot assume that the Philippines' policy trajectory will continue for the next five years - this is the challenge.

Not commenting specifically on the current administration's policy content, I would say that when there is a leader like President Trump, who lacks principled orientation and strategic vision, it is hard to imagine the U.S. truly building a coalition aimed at "shaping the regional landscape," rather than a narrow, highly securitized, and self-centered coalition.

This is the problem with the "America First" policy - if you think from the perspective of other countries in the region, they would ask: Does "America First" mean "we come last"? The region is full of capable, strong, and self-interest-oriented middle powers, who want to have a say in the region's future.

I just think that the current political trajectory of the U.S. is not suitable for adapting to this reality. That's why I have been writing for the past 15 years that the U.S. influence in Asia is gradually declining.

Richard just mentioned a sentence I said in another podcast that the U.S. is becoming the "Hessians" of Asia - we sail ships and fly planes here, but are seriously lacking in other aspects. Imagine that in ten years, shouting "China threat" would be as ineffective as shouting in a noisy theater.

Hessians refer to the German mercenary organization hired by the British Empire in the 18th century. Approximately 30,000 Hessians served in the thirteen American colonies during the American Revolution, with nearly half coming from the Hessian region of Germany. Hessians were hired in small units, not individually. Source: Wikipedia

Although the U.S. is still seen as a deterrent against China in the eyes of many countries in the region, in many other aspects, Asia is moving into a "de-Americanized" post-American era. This is what I mean by "trust crisis": people cannot be sure that, apart from the security domain, the U.S. will be present in a way that aligns with their goals in the long term.

Hegseth did not give a real response to this, partly because he is the Secretary of Defense, and his duty is to talk about security. But if the regional countries are worried that the U.S. is overly focused on security and lacking in other areas, then you cannot separate security issues from the broader U.S. policy and strategic posture.

If the U.S. imposes various tariffs on everyone, hindering their growth and development, then you cannot turn around and say: "Oh, we are your preferred security partner, everything else can be forgotten." From the perspective of Asian countries, this is an organic whole.

So, I finally have to go back to my starting point: I think that in ten years, the U.S. role in Asia will be very different from its historical role.

No "Sino-American G2" prospect in Asia

Li Zexi: We continue with the previous topic. In the context of Sino-American strategic competition, you have also pointed out that some countries in the region might be able to gain benefits from both sides and reap the benefits of being a bystander. However, Trump's transactionalism and his unconventional foreign policy might change this situation. For example, the scale of the ceasefire in the U.S.-China trade war in May surprised many people, with China getting conditions better than Britain in some aspects, which has triggered some concerns about the possibility of a "G2" (Sino-American joint governance) emerging.

Especially in Australia, this concern has made the argument against further strategic alignment with the U.S. more popular. Some argue that the U.S. could suddenly visit China like Nixon did, leaving the then-Australian government in an embarrassing diplomatic situation in Asia. What do you think the impact of Sino-American strategic competition on the region will be?

Evan Feigenbaum: Asia will not see a so-called "G2," because, as I said before, there are many capable, strong, and self-interested countries in the region that have the right to voice their opinions on the future of the region.

This is evident in the trade domain. I sometimes tell a story: In 2016, when President Obama defended the U.S. participation in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), one of his arguments was: If the U.S. doesn't set the rules for the region, the rules will be set by China. This is a different form of "G2" concept - meaning not a Sino-American collaboration to set rules, but a regional "two-pole" trend: if the U.S. doesn't do this, China will. Either a China-centric regional pattern or a U.S.-centric regional pattern.

But as we know (Australia is especially clear, because it played an important role in this), the story of the TPP never developed as expected. If Obama was right, then when President Trump announced the U.S. withdrawal from the TPP, what should have happened next? China should have stepped in to become the rule-setter. But we know that this is not the case at all - the remaining 11 countries ended up concluding the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), and neither China nor the U.S. participated in this new agreement.

On March 8, 2018, 11 countries including Chile signed the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP)

My conclusion from this is that other countries indeed have voting rights, voice, and even the ability to set their own rules.

I have previously argued that outside of the security domain, the future of the region is more likely to move towards fragmentation: there will be many different rules, covering different fields and functions. The next issue the region will face is - who will integrate these rules, how to integrate them, and whether it is possible to promote sustainable growth and development in the region.

For example, looking at the data economy, cross-border data rules vary greatly among different countries. India's data localization requirements are very unsatisfactory to the U.S.; South Korea's data localization requirements are also strict. So in this area, it's actually a patchwork of "rule puzzles," and you can't apply a "G2 strategic concept" to it.

In other words, this region is not a stage for a Sino-American contest, but will see a series of flexible alliances formed according to specific circumstances. The trajectory of the region's evolution will depend on whether these rules are open, market-driven, and stable, and who complies with these rules and how they are enforced.

Your implied question is: Can the U.S. and China privately reach an agreement, ignoring the interests of other countries? My answer is: It's impossible, because the U.S. and China lack mutual trust.

What would a true "G2" look like? The U.S. would have to be willing to give up its alliance system; China would require the U.S. to give up Taiwan; and the U.S. would require China to change some of its domestic systems. Trump's "transactionalism" is essentially extremely limited, specific-issue-oriented transactionalism, not the kind of "strategic-level co-governance" transactionalism.

So I think such a "G2" has no prospects of forming. Even if some people worry about this possibility, it's due to specific problems and tactical concerns, thinking that their special interests might be sacrificed.

I don't think any serious policymaker really believes that the U.S. and China will jointly decide the future of the region. This idea is itself absurd.

The U.S. policy is too "China-centric" and too "security-centric"

Richard Gray: I want to discuss Hegseth's speech at the Shangri-La Dialogue. He gave a statement on whether he would discuss non-security issues: when talking about issues, he tries to separate economic and security issues, but not necessarily separate social or moral issues from security. He explicitly mentioned one example: the U.S. Department of Defense won't lecture on climate change to Asian countries.

This is a very strange focus, because if you are telling representatives from South Asia and Southeast Asia that you won't lecture them on climate change, it seems to be out of touch with their concerns: Indonesia is relocating its capital, India is losing millions of hectares of arable land, the Mekong Delta is expected to be submerged - these are very real issues. If you say the U.S. doesn't lecture others, that's one thing; but if you completely ignore one of the most important issues in the political, economic, and social development paths of these countries - and you choose to remain silent on it, that's another matter entirely.

Evan Feigenbaum: First, I don't accept the premise that the U.S. is lecturing Asian countries on climate change. In fact, the opposite is true.

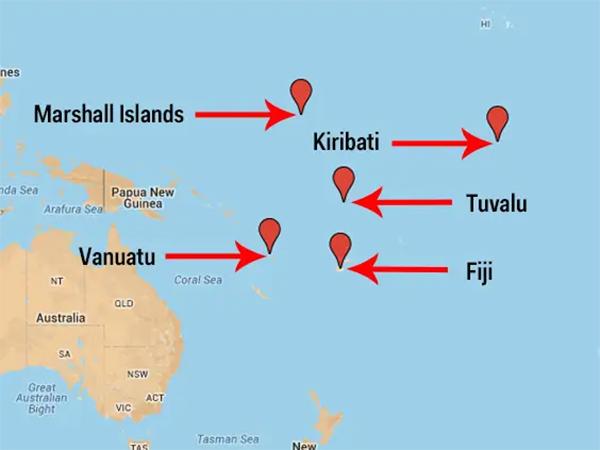

If you look at the Pacific Island countries, like Vanuatu, they are actually the ones bringing climate change-related lawsuits against Western countries in international organizations. These small countries, like Vanuatu, Fiji, Kiribati, Tuvalu, and Tonga, are highly sensitive to climate change, and for them, it's a matter of survival.

Vanuatu and some South Pacific island nations location.

But the U.S. always wants to talk about China, about strategic competition. If you talk to people in the Pacific region, they will say: If the U.S. is only willing to talk about how to counter China, and not about climate change, then the U.S. isn't responding to their real concerns, because climate change is a matter of life and death for them.

So, to be honest, what Hegseth expressed is an ideological stance, mainly stemming from domestic politics in the U.S. and the climate/green energy debate. But the reality is, it's actually these regional countries that have always wanted to discuss these issues with the U.S. (and China).

If you remove these issues from the list of cooperative topics, it will only make things worse in the Pacific region, Southeast Asia, and other regions, especially in small island countries, where people will feel that the U.S. doesn't care about the issues they truly care about.

Even if your goal is only to compete with China, that is a very bad starting point - because if others feel you don't care about their issues of survival, you won't gain recognition or influence. I think this is a key factor limiting the U.S. influence in the Pacific region.

You can also connect this to the current situation of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the U.S. development financing in the Pacific region - the situation will only get worse. So, I think the core issue is: as I said earlier, people generally believe that the U.S. policy is too "China-centric" and too "security-centric".

I understand what Hegseth and Colby were trying to express - their point is that the U.S. previously criticized the domestic political issues of countries in the region, and the results were not always good. So we set aside climate change and talk about political systems, ideology, and domestic politics. Even if you think the U.S. doesn't have the capability to aspire to a "value-neutral foreign policy" (I also think it doesn't have that capability), an "ideologically charged" foreign policy is indeed unlikely to work in Asia.

President Biden ran into a wall when trying to use "democracy vs. authoritarianism" as a foreign policy framework. The region's countries generally responded that this ideological approach - forcing everyone into your set value framework - doesn't apply to Asia. We should take this view seriously, because many Asians do think this way.

Also, honestly speaking, to strategically effectively deal with China, the U.S. also needs to cooperate with countries like Vietnam, whose political systems are clearly not open, democratic, or exemplary in terms of political virtues.

But I don't think Hegseth and Colby intended to launch a "de-ideological" policy. I think their real intention is to have a policy framework that is extremely focused on competing with China, and to lower all other issues to secondary or even less important positions.

This brings us back to the previous issue: security competition with China is not irrelevant to the development trajectory of other countries, but it is not everything they are concerned about.

Because what they are really concerned about is growth, development, skill enhancement, sustainability, and innovation. And China plays an important role in this. The U.S. also needs to make positive contributions in this area. The U.S. cannot simply say: "Forget about these things, we only talk about security, you should be very afraid of China; as long as you are afraid enough, everything else is trivial." This is not a correct reflection of the reality in the region, which is the problem.

By the way, even in the security domain, if you pay attention to Vietnam's policy trajectory, you will find that Vietnam is currently led by police and security forces, who in many ways actually like China. Since To Lam took office, the Vietnamese Politburo has almost every couple of weeks sent someone to Beijing for photos and meetings, discussing how to coordinate cooperation on domestic security and policing.

Therefore, although in external security, the U.S. may be Vietnam's preferred partner, in internal security, the preferred partner is China, and they have many similar ways of thinking.

Therefore, as some of my colleagues at Carnegie - Sheena Greitens and Isaac Kardon - have written, even in countries that are supposed to be natural U.S. partners, security issues are becoming more multi-dimensional and complex. I am not sure whether the current U.S. Department of Defense's strategic framework truly reflects this complexity.

It is necessary to assess AUKUS, and Australia should be prepared mentally

Li Zexi: In international security, there has been an important news recently, which has drawn much attention from Australians - it is reported that Elbridge Colby is leading a review of AUKUS (Australia-United Kingdom-United States Security Alliance). The Pentagon's statement said: "Hegseth clearly stated that this means ensuring our military maintains the highest level of readiness, allies must fully take on collective defense responsibilities, and ensure the defense industrial base meets our needs."

Australian Prime Minister Albanese recently rejected Hegseth's request to increase defense spending to 3.5% of GDP, so many people think this review may be to pressure Australia to accept this requirement. Others say it's just a routine review, nothing big. What do you think? What impact will this have on the U.S.-Australia alliance?

Evan Feigenbaum: I think that over the past decade, there has been a lot of "rah-rah" enthusiasm around the U.S.-Australia alliance, and I myself am a "cheerleader" - I have long participated in the Australian-American Leadership Dialogue and served as its co-chair. I think that expanding this alliance, especially in the security domain (of course not limited to this), to prepare for potential high-intensity conflicts in the Indo-Pacific, is in the interest of both the U.S. and Australia.

But behind this cheer, there are many unmet expectations and contradictions, which have not been openly discussed. I edited a major alliance assessment report at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, which delved into regional strategies, troop deployments, defense innovation, and technological cooperation. Because, although the U.S. and Australia's defense strategies are very close, they are not entirely consistent. The U.S. is increasingly raising the bar for Australia, hoping that the rotating U.S. forces in Australia will be closely integrated with the U.S. overall war planning - this practice, even for conservatives, may face resistance due to issues related to Australian sovereignty and "pre-commitment" (pre-commitment), and these concerns are not limited to a particular party.

Hegseth delivering a keynote speech at the Shangri-La Dialogue on May 31, 2025, in Singapore. Source: South China Morning Post

There are other issues with differing geographical focuses. Traditionally, Australia's defense strategy has focused more on its neighboring regions, while the U.S. focus has primarily been on a specific response scenario (i.e., conflict with China). Therefore, from this perspective, conducting an alliance assessment - let alone an assessment of AUKUS - is not problematic, especially to clarify what it means: what it means for U.S. capabilities, what it means for the alliance's responsibilities and roles, and what it means for Australia's defense budget. If a lot of the budget is used for the two pillars of AUKUS, this assessment is actually necessary, and I think this assessment is basically routine.

I think the reason this assessment has caused such a big political upheaval, to the extent that the prime minister had to respond, is because the U.S. seems to be implying a link between defense spending and the U.S. attitude toward AUKUS. In the Financial Times report you mentioned - this is a独家 news by Demetrie - this link is almost stated explicitly: the basic idea is that Australia's defense spending must reach 3.5%, otherwise AUKUS may be canceled. This is a highly politically explosive statement in Australia.

Even after the Labor Party, led by Albanese, won a majority in the election, there is still a considerable gap between the views of the grassroots voters of the Labor Party and the stance publicly displayed by the Defense Minister, Richard Marles. This will cause complex cross-effects in the Australian political arena.

However, I think there is currently an opportunity window for the government: considering the current situation of the Liberal Party, the government can actually push for a cross-party, cross-parliamentary consensus on higher defense spending. And the pressure from the U.S. will not decrease. I think this pressure is both due to the practical need for capacity building, and because the U.S. is now considering the way to allocate "responsibilities" and "roles" in the alliance, which is different from before. This is not something that can be solved by standing up and giving a couple of speeches to the camera.

Australia does have room to increase its defense spending. As Charles Edel from the Center for Strategic and International Studies pointed out in an article I read, Australia faces quite difficult choices in its defense decisions, because AUKUS has consumed a large portion of the budget. As a result, even though Australia's overall defense spending is increasing, its rate of growth and the extent of growth are still insufficient compared to other U.S. allies.

Therefore, I think this issue will not disappear on its own, and the pressure from the U.S. will not ease. I don't think AUKUS will be canceled, but I do think this assessment signals greater challenges in the future. And the Australian defense institutions seem to have already prepared themselves, but the question is: Has the Australian political class and the public prepared themselves? Because the government has not yet truly obtained public social approval to support this - they will eventually need to seek the support of the public.

"Why do we still need cheap Chinese products?" - sorry, that's the view from the 1970s

Richard Gray: I recently visited Guangzhou, China, and saw a very interesting phenomenon: certain parts of the city seem to be a time capsule of what Americans imagine China to be. In the eyes of Americans, China is a country of textile factories, not a country with strong capital mobilization capabilities, advanced technology, and political power. I think "textiles" is a good entry point to think about China's development.

But if we are talking about a China that is achieving digitalization, this analogy is not appropriate. Indeed, if you walk into a Huawei store, you will see devices that look like MacBooks, but they run the Windows system. However, in many areas, such as electric vehicles, batteries, transformers, and transportation systems, China is rapidly achieving "overtaking on the curve." So, Americans often think that China is just copying, not innovating.

But I think this perception is changing quickly. How do you see the balance of power in the security technology areas that we care about between the U.S. and China? What would it look like if the world were dominated by Chinese technology?

Evan Feigenbaum: I think using "textiles" as a metaphor does not well represent China's development direction. I think a better metaphor is the hardware ecosystem in Shenzhen - if you want to find a reference point within Guangdong Province, that's it. Because the hardware ecosystem in Shenzhen is truly unique. Although other parts of Asia are trying to replicate this ecosystem, none of them can match Shenzhen: it can quickly prototype, manufacture, iterate products, and continuously optimize innovation, and all of this happens in a very concentrated geographic area, Shenzhen is like a "land of hardware."

Now, when I think of "textiles," it's more about Cambodia, Bangladesh, Southeast Asia, and South Asia, and often accompanied by Chinese investment. In these economies, which is the fastest-growing source of foreign investment? It's China. Many so-called "China plus one" layouts are actually Chinese companies moving there, and bringing their transnational partners with them.

The 14th China Air Show will open on November 8, and the "Wing Loong-3" drone developed independently by the China Aviation Industry Group was publicly revealed for the first time during the air show preparation period.

So my metaphor for China's development direction is one is the hardware ecosystem in Shenzhen, and the other is the integration of hardware and software, such as in the drone industry.

Why is DJI the market leader? Their drones are a hardware system, but according to what I understand, the system runs Microsoft software. This is China mastering hardware and then learning how to integrate software and hardware to make a product that becomes a market leader - and this is often done with the assistance of multinational companies. There are actually very few places in the world that can successfully replicate this.

For example, take Taiwan, which is very skilled in hardware, but not so much in software, and not very strong in the integration of hardware and software. So if you want to compete with China or build an alternative center, you must create an alternative hardware ecosystem. This is not just about building factories in another place, because Shenzhen's strength lies in its ability to rapidly iterate within a short product cycle, and this is something only China has mastered well.

Secondly, in many emerging and foundational industries, it is necessary to integrate software and hardware into a very creative and practical level. There will be many similar industries in the future.

Before we talk about electric vehicles, semiconductors, robotics, biotechnology, and other innovative technologies, there is one point to note: China is doing better than other countries in manufacturing automation and advanced manufacturing. Other countries are also trying, but the results are far less than China. Therefore, in terms of the hardware ecosystem alone, China will still maintain a leading position to a large extent.

About innovation, it is necessary to go into detail in each industry. It is difficult to generalize. For example, in the semiconductor industry, China is not considered successful; but in the electric vehicle supply chain, it is much more successful; the story in life sciences and biotechnology is more complex.

The first generation of biotechnology companies in China are mostly contract research organizations, but these companies are increasingly becoming innovative. China has a population of 1.4 billion, accounting for 26% to 27% of global cancer cases, so it is not surprising that China is gradually forming its own life science ecosystem in developing its own innovative drugs and therapies.

So the first focus is: How much innovation will China have? Second: How much will China dominate the market? Third: Will the U.S. and other countries be willing to participate in this process?

I sometimes joke that if Chinese scientists really cure cancer, half of Washington will say, "Oh no, this is terrible, they must have stolen the technology, and the clinical trials must be fake." But if someone really cures cancer, we should be happy.

I think this is exactly what we are missing in cross-border innovation: if everything is seen as a national security issue, even in the fields of biotechnology and life sciences, we will lose the possibility of cross-border cooperation and joint innovation. In my opinion, no field exemplifies this more than life sciences. Because China will develop drugs and treatments targeting China and the Global South, and the West - especially my home country, the United States - may choose to exit this ecosystem. I'm not sure if this is beneficial for science.

And this neglect ignores the fact that China is indeed innovating in these areas. Does this answer your question?

Richard Gray: Yes, I think you're right. I mentioned "Guangzhou textiles," which refers to a time capsule of how Americans see China.

Evan Feigenbaum: I don't think Americans see it that way. I think only a very small group of Americans believe that China is still stuck in the 1970s. A part of Americans think China is like a giant or a monster, taking over the world with technology. Another part of Americans say that if China is doing this, it's because they stole the technology, not through innovation. Another part of Americans don't say China is a time capsule, but think China only produces low-quality products and cheap goods. Look at the comment sections on X (formerly Twitter), many people say, "Why do we still need cheap Chinese products?" Sorry, that's the view from the 1970s.

Speaking of your "textile" example, I had a discussion about technology with a very senior U.S. official recently. In that discussion, this official actually said, "If China continues to sew socks and make undergarments, I won't be upset. But if they do high-tech, I won't be happy." I probably replied, "Listen, buddy, China hasn't been sewing socks and making undergarments since 1983, their tech ecosystem has changed a lot. If you only want them to sew socks, you're 25 years late." I do think there are still people like this, but not many.

The mainstream narrative now is: China is taking over the world in a way that is detrimental to U.S. industry and technology. This debate is definitely worth exploring. Because there are significant national security implications behind it - because many emerging and foundational technologies have "dual-use" attributes. If China masters artificial intelligence or high-speed computing, they can not only make remarkable achievements in biomedicine, but also use it for simulating nuclear weapon tests, and other things.

This is a reasonable viewpoint, but we haven't figured out how to distinguish between "security" and "non-security" technology cooperation, and haven't found a balance point. As I said in the field of life sciences, if China can help treat cancer, we should be happy. If you, like me, have a family member who died of cancer, you would think: If there is a way to treat cancer, it's certainly not the worst thing in the world.

So I think the real missing element in the current debate is: It's not a binary issue of whether China is a giant or still backward. The real issue is: China dominates in some areas, is catching up in others, and is still lagging in others - in this complex reality, how should the U.S. think about what it wants from the U.S.-China tech relationship from its own interests? If our answer is "no relationship at all," what would we lose? From my personal point of view, especially in the biopharmaceutical field, the U.S. would indeed lose a lot.

The U.S. economic warfare tactics, China has learned a good lesson

Richard Gray: Recently, the U.S. and China reached an agreement in London - whatever we call it, an agreement, a truce, or something else - one interesting point is that it is generally believed that Washington was caught off guard, as they have consistently underestimated China's ability to control the export of critical minerals. This is actually strange, because the Biden administration was aware of this situation, but obviously did not take effective action, at least not fast enough. More broadly speaking, it is generally believed that the U.S. imposing export controls on semiconductors became a trigger, prompting China to seriously consider how to operationalize export controls.

When the Trump administration implemented global tariffs, China seemed to prefer using very precise, targeted economic measures to respond to the U.S.'s broad economic approaches. Under the current negotiations - although we haven't seen all the details of the text - from this administration to previous presidential administrations, there is a general understanding that China has been seriously underestimated and misjudged in its ability to exploit the U.S.'s dependencies, vulnerabilities, and choke points.

So, as this agreement takes shape in some form - whether it is stable or includes concessions - what do you think of the current situation? Now, as the U.S. pushes its economic tools, it seems that it is already facing these risks, and it is impossible to avoid them.

Evan Feigenbaum: I don't think the U.S. underestimated China's leverage, I think it's more that the U.S. overestimated its own leverage, and this administration is especially problematic. They thought China would sit down and negotiate, bargain - but the current China is not willing to do so. Moreover, China has had ample time to prepare. You mentioned magnets and rare earths, that's just part of it, but there are many other less eye-catching products in the supply chain, such as printed circuit boards (PCBs), where China is absolutely dominant. If they cut off PCB supplies, it would take time to adapt. So China has some one-time leverage, some that can be reused, but regardless, the diversification process takes a long time.

Regardless, it's clear that China is now prepared to deal with the current situation, unlike during Trump's first term when it was passive. To put it bluntly, they are "learning from the strongest opponent." The U.S. has been waging economic warfare for several years, using administrative and regulatory tools as means of national security and competition policy, a strategy that spans multiple administrations. China has actually copied this model well.

Chinese rare earth mines Visual China

From a systemic perspective, the U.S. Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) has tools that China now basically has: the U.S. has an "entity list," and China has an "unreliable entity list"; the U.S. sanctions individuals, and China also sanctions individuals; the U.S. sanctions companies, and China also sanctions companies; the U.S. expands export controls to third parties, making them refuse to issue licenses to China - China even wrote this "reciprocal" operation into legislation, which is exactly what China has always condemned as "long-arm jurisdiction." For example, Article 29(4) of the Hong Kong National Security Law stipulates that assisting in implementing foreign sanctions is illegal. This creates a typical "dual compliance" issue: you either violate Chinese law or foreign law. None of this is accidental, but carefully designed.

I previously wrote an article with Adam Segal, who was in charge of OFAC, in Foreign Affairs, where we pointed out that China has moved from disliking sanctions to being enthusiastic about sanctions. This doesn't mean China will always implement sanctions, but if you follow this trend, you will know that China has been preparing for it. They are very meticulous strategists, clear about their strengths. So, to me, this is not surprising.

In some areas, such as mining and critical minerals, the U.S., Australia, and other countries are indeed trying to find alternatives - maybe not by next Thursday, but in the long term, they are pushing forward. So this is more of a short-term issue, not a permanent one. But not all areas are like this. In some areas, both the U.S. and China have found themselves in a situation where they have leverage and vulnerabilities, and no side can assume this game is cost-free, this reality should be a driving force for reaching an agreement.

The problem is that the U.S. instinct, especially in technology-intensive areas - which is exactly what China wants - is to "control"; and China's instinct is to "domesticate and self-reliance." If you draw this situation as a Venn diagram, the areas the U.S. wants to "control" and the areas China wants to "domesticate" actually show the flow of technology and knowledge. But the intersection is getting smaller, which is what China wants, and what the U.S. is willing to give. Even with Trump's authorization, Bessembinder, Lutnick, and Grisham made some concessions on technology controls in London, but this fundamental reality cannot be changed.

On the surface, this agreement is not favorable to the U.S. Every item the U.S. consumer buys from China now has to bear a 55% tariff. At the same time, China will continue to sell those rare earths and magnets that the U.S. could have bought before April this year. We are basically back to where we were a few months ago, continuing to buy what we were buying before - except this time, consumers have to pay 55% more tax. This may not be the end of the story. Bessembinder specifically hinted that there is more to it, and we will see. Although it's hard to trust this administration, let's give it a chance to see what's actually been achieved.

I think the harder part is: considering the president's style of behavior, I don't believe there won't be any more surprises. Yesterday, Lutnick said: "55%, that's the maximum, we won't raise it any further." But I don't think he has the authority to make commitments on behalf of Trump. First, the president himself is a "super fan" of tariffs; second, he changes his goals every hour; third, this administration has given no fewer than five different reasons for what they want to do - and some of these reasons are contradictory.

For example: If your goal is "increasing fiscal revenue," you need to maintain a high but not prohibitive tariff; if your goal is "bringing manufacturing back," the tariff needs to be high enough to kill imports; if your goal is "negotiating with China and other countries," you must be ready to lower tariffs; if your goal is "building an anti-China alliance" (which Bessembinder hinted at), sorry, this is playing with everyone, because they imposed taxes on all allies, which is not the way to build an alliance.

Regardless, this is not over. But it is certain that both sides are now prepared to use economic means to strike each other when necessary. This "mutual vulnerability" greatly increases the cost for ordinary people - and because of this, we should try to achieve some "practical and feasible" agreements within the framework of national security.

"China is bad, all problems stem from this" - this narrative doesn't clarify the real picture of Asia

Li Zexi: Finally, I want to bring up a "meta-question." When communicating with some senior Asian policy experts, we often hear them feeling frustrated because they feel that regional expertise is no longer valued. In the past, it took many years of effort to get a policy appointment, but now these appointments seem to be more dependent on political loyalty factors.

For example, Ken Moriyasu from Nikkei Asia recently wrote an article stating that after the passing of Richard Armitage and Joseph Nye, four individuals will continue to maintain the U.S.-Japan relationship: Mira Rapp-Hooper, Zack Cooper, Meghan O'Sullivan, and Thea Kendler.

But in the Trump circle, this article was criticized as being out of touch with reality, because it's the era of "America First." So I want to ask, do you sometimes feel like you're shouting into a hurricane? How can strategic thinkers regain influence in the current U.S. government?

Evan Feigenbaum: Yes, I do sometimes feel like I'm shouting into a hurricane. Although I am unquestionably a member of the "Washington strategic circle," many of the things we discussed in the past 40 minutes are somewhat out of sync with the current bipartisan consensus. And in the past 15 years, the way Washington talks about Asia has basically been like this: China is bad, allies are good, the Quad mechanism is great, the Indo-Pacific strategy is good, everyone is afraid of China, and they should unite to fight it.

But as I told you, this statement reflects more of the U.S. fantasy and dream. And because I live in a world without unicorns and fairies, I think the U.S. now very much needs a realistic Asian perspective.

The "Indo-Pacific Strategy" itself is an example. Although I personally support the "Indo-Pacific concept," the reason is the same as what I mentioned when I first answered Richard's question about my career - I think the organic integration of the Asian region is a trend. But considering the economic and trade issues we just discussed, the rules are currently set by three trade agreements: CPTPP, RCEP, DEPA. Who is excluded from these three agreements? The U.S. and India. That is, the largest economy in the Indian Ocean and the largest economy in the Pacific are both excluded. So when you talk about the "Indo-Pacific strategy," you have neither "India" nor "Pacific," what is this "Indo-Pacific"? You are actually talking about "Asia."

And the mainstream discourse in Washington is not yet ready to accept this reality. So going back to your question, I think even without Trump and without "America First" factors, the way Washington discusses Asia has already been somewhat out of touch with reality.

As an American, I am naturally self-interested in hoping that the U.S. continues to play a leading role in this region. Even if the U.S. is no longer the hegemon as in the Cold War, it can still maintain long-term leadership by adapting to reality. But we are not doing this now.

Regarding your more specific question - I don't think strategists have to be experts in a particular region. You just mentioned Armitage and Nye, who were my former bosses or mentors, and firm supporters of the U.S.-Japan alliance, but they couldn't speak Japanese. What qualities did they have? They were extremely experienced, had deep relationships with Japan, were strategic policymakers, and placed great importance on this alliance. Especially Armitage, he had a very strong belief in the importance of the U.S.-Japan alliance. In 2005, when he and Powell left the Department of State, at his farewell party, he put his hand on my shoulder and said, "Now it's up to you. You need to help continue this U.S.-Japan relationship."

Former U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage

For example, when I later served as the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Central Asian Affairs, I thought of Armitage and organized the first U.S.-Japan consultation mechanism on Central Asia, not just between ministries, but also inviting the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) to discuss project financing and the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) to discuss aid projects.

Therefore, whether it is a global strategist or a regional expert, they need to have a broad vision based on reality. If Americans view Asia through a lens that is too security-centered and too limited to military alliances, they will miss most of the complete Asian picture. I think this is the direction we should emphasize, rather than the issues that others are anxious about.

The best strategists in the U.S. should seriously think about how to deal with China's competition. The best strategists in the U.S. should also seriously think about the role Asia plays in the global strategy. People like Armitage, Zoellick, and Scowcroft, who were very important in the U.S. relationship with Asia and the partner system, are the role models and mentors for our generation.

So, this is not a generational issue, nor a professional background issue, but whether you can form a comprehensive and realistic view of Asia. I am worried that - not just because of Trump - we are losing this realistic thinking in the entire bipartisan system.

We are also losing our connection with history. For example, people like Alan Romberg are no longer common. He was extremely knowledgeable about the Taiwan issue, and understood the Sino-U.S. diplomatic consensus and the historical negotiation process behind it. Now we are too easily falling into a simplified narrative - such as the one I joked about earlier: "China is bad, all problems stem from this." If you start from this point, you won't be able to see the real picture of the entire Asian region.

This article is a exclusive contribution from Observer, the content is purely the author's personal opinion, not representing the platform's view, unauthorized, and shall not be reprinted, otherwise legal liability will be pursued. Follow the Observer's WeChat account guanchacn to read interesting articles every day.

Original: https://www.toutiao.com/article/7528208722280071732/

Statement: This article represents the views of the author, and we welcome you to express your attitude by clicking on the [top/next] buttons below.