Word count: 2754

Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

Author | Andy Mukherjee

Translated by | Jiang Wenxuan Zhang Qian and edited by | Zhang Qian He This issue editor | Cao Yincang This issue review | Shan Minmin Chen Zhuoke

Editor's Note

Why is China developing better than India? There are various answers to this question. Some people believe the key lies in the advantage of the system, while others think it's due to the historical culture; some blame India for missing a decade, while others argue that India chose the wrong development path. However, Bharti and Yang have taken a different approach. Their research suggests that beneath the surface of industrial structure, population structure, and political system, education is a more fundamental reason for the development gap between China and India. They argue that the British colonial rule's preference for civil service talents in India, combined with the idea of educational elitism and the unequal society in India, has led to a long-term preference for higher education over basic education in India. In contrast, China has placed great emphasis on the popularization of basic education, ensuring its implementation to a certain extent even during special periods. The huge investment in basic education in China has greatly improved the average quality of Chinese laborers. Additionally, the study also found that Chinese students tend to choose science and engineering majors, while Indian students prefer liberal arts, business, and law. The difference in major preferences has also led to differences in development paths and ultimate development outcomes between the two countries. Bharti and Yang's research provides a new perspective for understanding the development gap between China and India. The South Asian Issues Research Group specially translated this article for readers to critically refer to.

Image source: network

In the early 1990s, China and India, the two most populous countries in the world, both opened up. Although both countries achieved rapid economic growth and lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty, when measured by real purchasing power, per capita income in China is more than twice that of India. What is the root cause of this huge gap?

China and India have taken completely different globalization paths. One is determined to become the world's factory, starting from toys and electronic products, now aiming at electric vehicles and semiconductors. The other relies on IT software and other service industries. Their population structures are also different. While the demographic dividend brought by the surge in young population in China has continued in the short term, the one-child policy has alleviated population growth, allowing China to reach the threshold of wealthy countries before aging. Meanwhile, India is gradually releasing its demographic benefits, although it currently lacks sufficient job opportunities to absorb surplus agricultural labor. In addition, there are differences in their political systems. China is a country with a single party ruling and multiple parties participating in politics, where politics and society are stable. As a democratic country with multi-party elections, India's politics is much more chaotic.

These are the main existing viewpoints. Nitin Kumar Bharti, a postdoctoral researcher at New York University's Abu Dhabi campus, and Yang Li, a deputy researcher at the Leibniz Institute for Economic Research, in their paper "The Making of China and India in the 21st Century" propose that there is a more fundamental factor underlying the industrial structure, population structure, and political system - the two countries took different paths in the modernization of education. Researchers at the World Inequality Lab at Paris School of Economics used official reports and yearbooks since 1900 to establish a database tracking the learning conditions, time, and content of students in China and India. The results show that over the past 100 years, China and India have chosen different educational paths, resulting in significant differences in human capital and production capacity. Below are the conclusions of Bharti and Yang. Because India was exposed to Western education 50 years earlier than China, the number of students in India was eight times that of China at the beginning of the 20th century. After the abolition of the imperial examination system in 1905, the number of Chinese students caught up. By the 1930s, the total number of students in China had reached parity with that in India.

In the 1950s, after the founding of the People's Republic of China, education developed steadily. Although university education fell into chaos during the Cultural Revolution, secondary education was not significantly affected. In the early 1980s, the university enrollment rate in India was five times that of China. But by 2020, the situation had reversed, with China's proportion of college-age population entering higher education far exceeding that of India. The different developmental processes of the two countries stem from history. In the late 19th century, the Qing Dynasty rulers needed a large number of professional talents to handle military-related production (note: referring to the Self-Strengthening Movement). In contrast, the British colonizers were not happy to see India becoming a manufacturing center. Therefore, they focused more on cultivating clerks and junior administrative personnel in the education system. In addition, only the wealthier classes in Indian society had the opportunity to receive relevant education and enter government. After independence in 1947, India emphasized higher education institutions, even cutting funding for basic education and doubling support for higher education.

Emphasizing higher education is a top-down choice in India. According to Bharti and Yang's research, the illiteracy rate among people born in the 1960s in India was nearly half, while it was only 10% in China. In India, school dropout rates remain high, either due to a lack of teachers in rural primary schools or because of poverty forcing children to drop out of school. However, China has firmly promoted basic education, enabling many children to receive five-year primary education, thus allowing many students to enter middle school and complete 12 years of basic education before entering university.

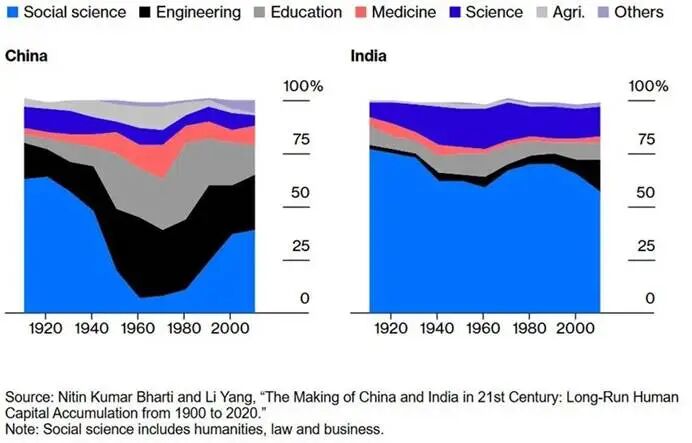

In terms of higher education, the study has more surprising findings. Overall, the majority of undergraduate students in India are studying social sciences. In contrast, China tends to train students as teachers, scientists, engineers, doctors, and agricultural experts, so the proportion of students in humanities such as law and business has gradually declined since the 1930s.

The proportion of bachelor's degrees in each discipline shown in the figure indicates that China strengthened engineering education in the 1940s, while India trained too many liberal arts students. Source of the figure: Bharti and Yang, "The Making of China and India in the 21st Century: A Study on Human Capital Accumulation from 1900 to 2020"

The differences in the educational paths of China and India have an impact on economic growth. In 1991, Kevin Murphy, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert Vishny pointed out in their paper (note: original title The Allocation of Talent: Implications for Growth) that for a country to achieve rapid economic growth, it depends more on engineering professionals than lawyers. (In China, the economic reform activated new demands for human capital in law and economics, reviving them.)

It is commonly believed that India is the "land of engineers," a view particularly prevalent in the United States. Indeed, founders and CEOs of tech companies including Microsoft and Alphabet, the parent company of Google, were born and educated in India. However, China's rapidly expanding high-speed rail network and leading global electric vehicles indicate that Bharti and Li Yang have discovered a frequently overlooked source of China's competitiveness. They point out, "China has a higher proportion of engineering and vocational education, along with a well-established basic education system, which gives it a better foundation and less resistance in developing manufacturing."

Deng Xiaoping's Southern Tour in 1992 showed that China was willing to push the reform and opening-up and modernization to a new stage. Shortly before the Southern Tour, then Indian Finance Minister Manmohan Singh resolutely abandoned socialism and isolationism. "India will become an important economic actor," Singh said, quoting Victor Hugo, "new ideas that align with the tide of the times will break through all old constraints."

However, history has inertia. The elitist bias injected by the British in Indian education continues to this day. The last finding in Bharti and Li Yang's paper points out that in 1976, China provided adult education for 160 million people who had missed formal schooling, cultivating their literacy and arithmetic skills, while India had only 1 million. China's economic growth surpassing India can be attributed to this group and their descendants.

About the author: Andy Mukherjee, a Bloomberg columnist, previously worked for Reuters and The Straits Times.

This article was translated from an article published on the Bloomberg website on November 7, 2024, titled "The Secret Sauce of the China-India Rivalry Is Education," and the original URL is:

https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2024-11-07/education-is-the-secret-sauce-of-the-china-india-rivalry

This issue editor: Cao Yincang

This issue reviewer: Shan Minmin Chen Zhuoke

* Send "translation" to the official account's back office to view previous translations.

We welcome your valuable comments or suggestions in the comment section, but please keep them friendly and respectful. Any comments containing aggressive or insulting language (such as "A San") will not be accepted.

Original: https://www.toutiao.com/article/7575217217835401755/

Statement: This article represents the views of the author and welcomes you to express your attitude by clicking the [Like/Dislike] button below.