"Europe must not let the US and China alone decide the future of technology."

Behind German Chancellor Merkel's statement, it is evident that Europe is anxious about falling behind China and the US in future technology and key supply chains. The business community has had to dance to the politicians' "baton," which has already been demonstrated under the EU's so-called "de-risking" strategy.

Under the backdrop of increasing international geopolitical uncertainty, what choices do European companies operating in China face? What are the thought-provoking considerations behind practices such as "producing for China" and reinvesting profits? Observer Net interviewed Professor Ding Chun, Director of the Center for European Studies at Fudan University, to bring his insights.

[Interview / Observer Net, Guo Han]

Observer Net: You mentioned at the recent China-Europe Association annual meeting that the strategies of large enterprises from Europe in China have shifted from "producing for the world in China" to "producing for China in China." Could you talk about the deep background and the considerations of the enterprises behind this shift?

Ding Chun: In fact, this shift did not happen overnight but was a gradual process over a period of time. If we look for a landmark event, it may trace back to 2019 when the EU formally proposed the "threefold positioning" of its relationship with China—defining China simultaneously as a partner, an economic competitor, and a systemic rival. Following this, the "de-risking" strategy and the 2023 "Economic and Security Strategy" document were successively introduced, leading to today's situation.

There are both structural factors and short-term triggering factors behind this. For example, the pandemic stimulated the vulnerability of the "just-in-time" supply chain model that was popular during the era of globalization, which pursued zero inventory and low costs. The outbreak of the Ukraine conflict has also impacted Europe, along with factors such as geopolitical risks and non-traditional security issues. Structural factors are related to the development of China's economy, especially the upgrading of its manufacturing industry. Previously, Europe mainly exported technology and capital to China, and China achieved industrial growth through "market-for-technology." At that time, Europe saw China more as a strategic partner, especially within the context of the great game between the US and the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

As time went on, China's own manufacturing capabilities have strengthened, and it has now become the second-largest economy in the world. The differences in perception between China and Europe regarding developmental stages, institutional concepts, and social issues have gradually become larger. Including interference by the EU in China's internal affairs, challenges faced by Europe internally such as the influx of refugees, the rise of populism and anti-globalization forces, and the continuous pressure from the United States, all these have placed new structural pressures on Sino-European relations.

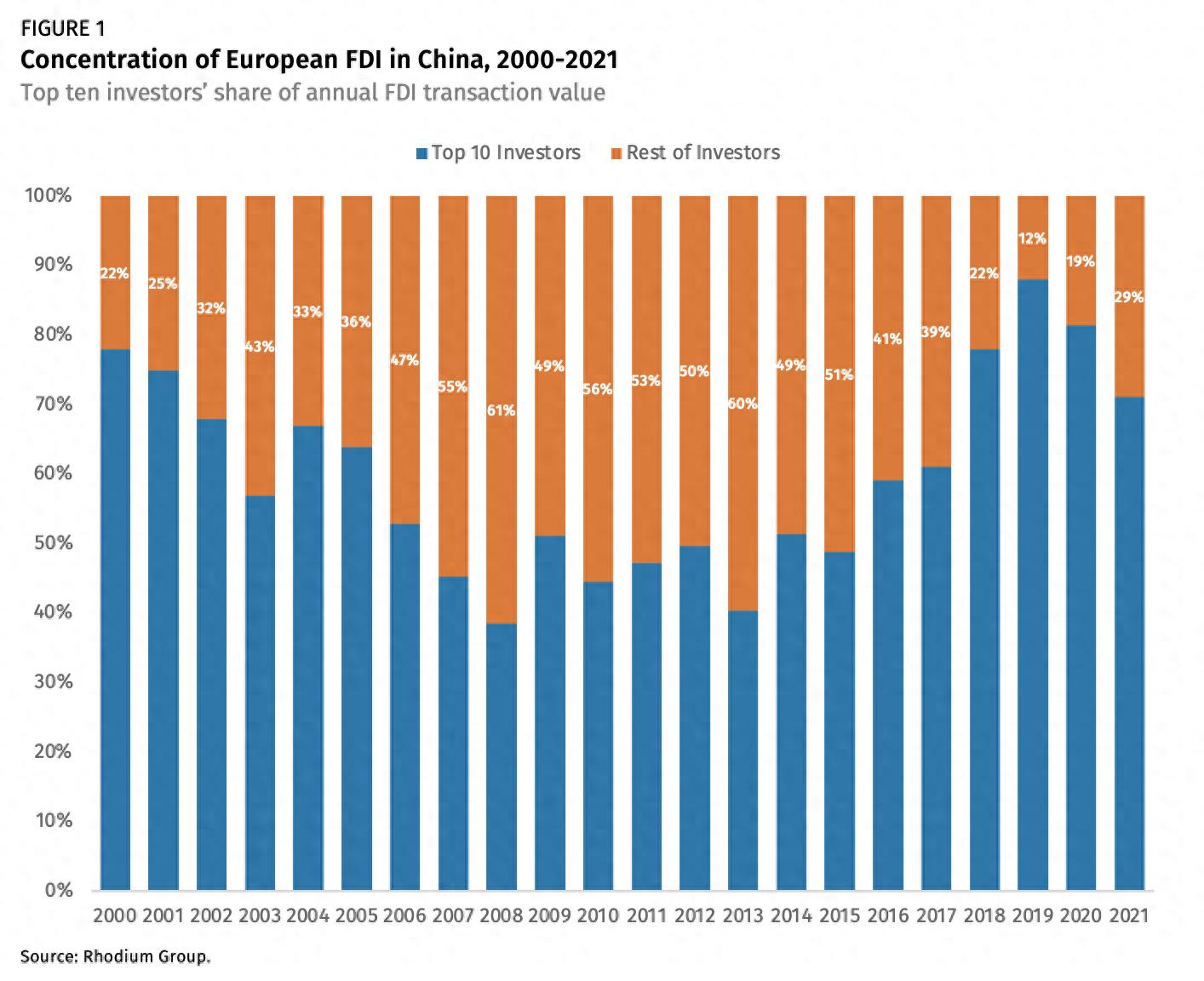

Concentration of direct investment from Europe to China (2000-2021), blue represents the top 10 investors, orange represents the remaining data source: Rhodium Group

From an economic perspective, the pandemic exposed the fragility of the "just-in-time" supply chain model that was popular during the era of globalization, which pursued zero inventory and low costs. Now, the safety of the industrial chain has become a new focus for Europe. Geopolitical risks and non-traditional security issues have made "accessibility" a new keyword. Coupled with the previous influence of European politicians' perceptions of China and various differences of opinion on related issues, "de-risking" and "reducing dependence" have gradually become the core logic of European policy.

Under this context, the investment ideas of some European enterprises have indeed changed. According to our observation, European enterprises investing in China have been implementing "de-risking" measures, although the situations of large enterprises and small and medium-sized enterprises are not entirely the same.

On one hand, as China's own manufacturing capabilities have improved, its competitiveness has become stronger, and investment enterprises from Europe or their imports and exports of technology and goods have felt significant competition. If they lose their comparative advantages in the domestic market environment, combined with the impact of the aforementioned objective factors, some European enterprises will indeed consider making adjustments.

But for other enterprises, the change in their investment ideas is reflected in the fact that in the era of globalization, they previously promoted setting up factories in China to serve the global market (In China for Globe). They treated China as a node in their global industrial chain and supply chain. Now, many of these enterprises have shifted to setting up factories in China to serve the Chinese market (In China for China). That is, primarily targeting the Chinese market. On the surface, there is no problem, but this actually means that some European enterprises want to avoid geopolitical risks while not wanting to give up the Chinese market. They tend to establish a more complete localized supply chain in China, transforming from a single node into a relatively complete industrial chain system centered on China to meet the needs of the Chinese market.

This leads to a somewhat intriguing phenomenon: the so-called "increased investment" — some foreign enterprises are increasing their investments in China, strengthening R&D and local production links, but their purpose is often to "de-risk".

Although it cannot be generalized, some large European enterprises in industries such as automobiles and chemicals are still increasing their investments in China against the trend, actually using their operating profits in China for reinvestment. For example, in the automobile industry, the profit from some European car companies in the Chinese market accounts for three to four times of their global profits. They cannot easily give up such a big market.

At the same time, China has a comparative advantage in areas such as new energy vehicles and batteries. For example, European enterprises such as Volkswagen and BMW, which have strong research and development and technological reserves, do not feel that they will be completely defeated or replaced by Chinese enterprises. They choose to accept the pressure test of the Chinese market, cooperate with Chinese enterprises in R&D, and compete together. This is also a way to enhance their own enterprise capabilities and keep up with the development trends of the industry.

In this sense, the practices of these enterprises are worth praising. Because the development of industries and technologies is essentially a process driven by mutual competition and cooperation. For European enterprises that are relatively confident and willing to cooperate and compete, we should express our welcome.

Regarding the large investment of BASF from Germany in Zhanjiang, Guangdong, it belongs to another case. The underlying logic is that since the Russia-Ukraine conflict has exacerbated the energy crisis in Europe, energy-intensive enterprises and industries have been suffering from long-term price increases. Facing this situation, if they do not take the opportunity to promote transformation and upgrading, those enterprises will have no way out. Therefore, BASF's investment in China is also a timely decision made from the perspective of long-term industry development and global strategic layout.

In summary, these enterprises' decisions reflect confidence in the Chinese market and the consideration of enhancing their own technology and diversifying risks through cooperation. Enterprises that maintain confidence, dare to cooperate and compete, are more resilient. On the contrary, for example, some enterprises in Italy and France hope to rely on their government to raise tariffs and adopt protectionist measures, and their prospects will not be good.

Additionally, China's complete and efficient industrial chain and supply chain system, including the high cost-performance production capacity and product support brought about by "internal competition," as well as the Chinese government's continuous optimization of the business environment and investment environment (such as providing visa convenience, holding the China International Import Expo, and aligning with agreements such as CPTPP and DEPA), have also formed a continuous attraction for foreign enterprises. Especially the recent Fourth Plenary Session and the formulation of the "15th Five-Year Plan," which have released very important positive signals.

Observer Net: Recently, there has been discussion within Europe about requiring Chinese enterprises to implement "mandatory technology transfer," especially in the fields of electric vehicles and batteries. Is this a short-term urgent issue, or does it represent a more systematic consideration by the EU?

Ding Chun: Overall, Europe is currently facing "internal troubles and external threats." On one hand, internal economic growth is weak, and on the other hand, it feels serious anxiety in the competition with China. Its scientific research investment and technological accumulation are being gradually caught up, and this anxiety is reflected in policies. The EU has recently introduced a series of measures, such as the Foreign Subsidies Regulation (FSR), foreign investment review mechanisms, and anti-subsidy investigations.

Recently, I visited Europe and visited the China-EU Chamber of Commerce, where I learned about some concerns of Chinese enterprises investing in Europe, including facing FSR investigations, telecom enterprises being labeled as "unreliable suppliers," regulatory authorities suddenly conducting inspections on Chinese enterprises and excluding relevant Chinese enterprises from centralized procurement, etc., as well as the requirements currently being discussed by Europe to require Chinese investment enterprises to implement mandatory technology transfers or meet specific localization conditions, all reflecting such an overall trend.

Behind this, there are both economic competition and political and security considerations. The EU has 27 member states, and their trade and economic relationships with China differ greatly. Countries such as Germany, Spain, Hungary, Czech Republic, and Slovakia have closely cooperated with China in the fields of new energy vehicles and batteries in recent years, and their attitudes are relatively pragmatic. Among them, Germany itself has a market share in traditional oil cars in China, and the impact on the overall profits of enterprises is significant, so they are more opposed to increasing tariffs on Chinese new energy vehicles.

While countries like France and Italy, whose related industries have weaker competitiveness, are more inclined to push for protective policies. Some countries, such as Denmark, although they have no automotive industry, have chosen to "follow the crowd" on tariff issues for the sake of "internal unity." Overall, Europe is increasingly anxious and losing confidence in its ability to compete with its related industries, and it is taking restrictive measures such as labeling Chinese investments or suppliers. This overall trend is tightening, but there are obvious differences in the positions and actions taken by different member states on specific issues.

Observer Net: Regarding the U.S.-Europe relationship, the steel and aluminum tariff agreement signed by the U.S. and Europe has come into effect in September. How do you view this agreement? Does Europe believe that the trade disputes with the U.S. have been properly resolved, or are there still potential changes? Additionally, the U.S. is also urging Europe to align with it on sanctions against China. How does the EU balance this?

Ding Chun: The current agreement reached between the U.S. and Europe is very complex, not just a simple trade issue, but a political compromise made by Europe after comprehensively considering security and trade issues. It can be said that this agreement has avoided a full-scale trade war between the U.S. and Europe, but in essence, it is an unequal agreement.

Local time October 23, 2025, Brussels, Belgium, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, French President Emmanuel Macron, and German Chancellor Merkel talking. Visual China

Europe has a dependency on the U.S. in terms of the Ukraine conflict, NATO, and other security issues, and does not want to clash with Trump, so it has made concessions in the economy. Originally, the U.S. and Europe, as developed economies, had very low tariffs on a large number of goods traded between them. However, Trump once threatened to impose a 27.5% tariff on cars imported from Europe, and finally, the two sides stabilized it at 15%. Although Europe has paid a higher cost, it had to accept this "second-best solution" to obtain certainty and avoid conflicts. Countries such as Germany, Italy, and Ireland have adopted similar pragmatic attitudes.

However, this agreement itself leaves a lot of "loopholes," and many specific areas still need re-negotiation, such as agricultural products and spirits. In fact, it is a temporary agreement with political significance aimed at avoiding confrontation between the two sides. In addition, as a union of nations, the EU has certain trade and investment powers, but it cannot force member states' enterprises to invest according to U.S. requirements, especially since there are significant differences in the levels of industrial development and comparative advantages among member states. Therefore, the implementation of this agreement will require a long process of negotiation.

Regarding the possibility of Trump pushing for a second round of tariffs on China, I think Europe will not fully follow. Politically, Europe may align with the U.S. on a few issues, such as China's rare earth export controls, but will not completely copy the U.S. approach. For example, Trump threatened to impose a 100% tariff on China on the issue of rare earths. This is because the interests of the U.S. and Europe on the rare earth issue are relatively consistent.

But Europe must consider that it is an important trading partner with China, and the two are highly interdependent. If extreme measures are taken, it would inevitably trigger countermeasures from China, and the consequences of a trade war would be difficult for Europe to bear. Moreover, the U.S. and Europe have similar economic structures, so there is also a certain interaction and competitive relationship.

Furthermore, achieving consensus among so many EU member states is not easy. Therefore, the U.S. and Europe will coordinate in direction, but maintain a certain distance in implementation. They need to avoid confrontation with the U.S., while considering the practical interests with China. This is their logic of balancing.

In summary, the current state of Sino-European relations is in a relatively low period, but not a period of confrontation. Especially in the field of trade and economy, mutually beneficial cooperation remains the most practical and core part of bilateral relations. Since both sides are important trading partners and cannot do without each other, they should seek a "second-best solution" during difficult times—especially under the current situation of continuous geopolitical conflicts and sluggish global economic recovery. Even if it is not the best interest for each side, they should pursue a solution that both can accept, to avoid a "double loss."

Secondly, if some symbolic, politically colored macroeconomic trade issues are difficult to resolve in the short term, then it is possible to start from a specific area, truly solidify the foundation of bilateral economic and trade cooperation, and promote the maintenance and continuous development of bilateral relations through accumulating small steps. Instead of just seeing problems and condemning the other party, or exacerbating contradictions and conflicts. This pragmatic approach may be more effective in promoting the healthy development of Sino-European relations.

This article is an exclusive article by Observer Net. The content of the article is purely the personal opinion of the author and does not represent the position of the platform. Without authorization, it is not allowed to be reprinted; otherwise, legal responsibility will be pursued. Follow the WeChat account of Observer Net, guanchacn, to read interesting articles every day.

Original: https://www.toutiao.com/article/7568313794389918249/

Statement: This article represents the personal views of the author. Welcome to express your attitude by clicking on the [top/vote] button below.