【By Observer Net Columnist Guan Jianqiang】

On January 26, Japanese Prime Minister Takahashi Hayato once again made inflammatory remarks on the Taiwan issue, not only failing to show remorse but even deliberately provoking.

Upon a closer look at Takahashi's political career, it can be described as "riddled with misconduct."

Last November, after Takahashi Hayato made erroneous statements about the Taiwan issue, netizens uncovered an old video: On October 12, 1994, as a member of the Japanese House of Representatives, Takahashi Hayato engaged in a debate with then-Prime Minister Murayama Tomiichi in the Diet. This seven-minute and one-second video has been widely circulated on the internet.

In the video, Takahashi Hayato questioned aggressively, while Murayama Tomiichi responded calmly. Throughout the debate, Takahashi Hayato did not gain the upper hand and left empty-handed. The questions raised by Takahashi Hayato revealed his eagerness to justify Japan's wartime aggression and atrocities against humanity. At the same time, the entire exchange also demonstrated Takahashi's limited understanding of relevant laws. It is necessary to conduct the following legal analysis.

I. Does the "fault" mentioned by Prime Minister Murayama refer to a "fault" with legal basis?

1. Takahashi's Question and Murayama's Response

At the beginning of the questioning, Takahashi asked: "In my constituency, members of the Association of the Families of the Fallen Soldiers have questioned me: 'Were those who were conscripted and never returned really participating in an invasion war?' Additionally, the priest of the Nara Yasukuni Shrine was upset because he received harassment calls saying, 'Are those you are worshiping criminals?' and shed tears of regret. For these people suffering, today regarding the issue of the invasion war, I hope you can give a more specific explanation than before. ... At the August National Memorial Ceremony for War Dead, you used the phrase 'the Asian neighbors who suffered heavy casualties due to our fault.' Specifically, what actions could be considered acts of aggression? Also, what exactly does the Prime Minister mean by 'fault'? Is it a 'fault' with legal basis? Please answer that as well."

Murayama: "I used the terms 'aggressive actions' and 'colonial rule,' referring to the actions of the Japanese army gradually and continuously attacking mainland China and entering various countries in Southeast Asia during this prolonged war. The aggressive actions I referred to are these."

Takahashi: "Then, this is not a 'fault' with legal basis, right?"

Murayama: "No, I'm not sure which law you're referring to when you say 'legal level.'"

In this round of questioning, Takahashi sought to extract from Prime Minister Murayama that such "wrongdoings" were moral responsibilities outside the law. However, Prime Minister Murayama denied the logic of the questioner and reasserted, in simple language, "The aggressive actions I referred to are these," in response to Takahashi's question "Were those who were conscripted and never returned really participating in an invasion war?"

Although Prime Minister Murayama clearly identified Japan's aggressive actions, he did not explicitly point out which legal prohibitions were violated by Japan's "wrongdoings." Therefore, it is necessary to supplement the legal basis for the illegality of "past aggressive actions and colonial rule."

2. "Were those who were conscripted and never returned really participating in an invasion war?"

The Japanese invasion of China and the Pacific War seriously violated the prohibition of the Paris Peace Treaty on the use of force, and thus this war has been judged by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East as an illegal aggressive war under international law. In addition, although the San Francisco Peace Treaty has many illegal or invalid clauses in procedural and substantive law, since China was not a signatory, the San Francisco Peace Treaty does not have binding force on China. However, according to the universally recognized principle of international law, "treaties do not bind third parties," but "if a treaty creates rights for a third party, that third party may enjoy the rights if it agrees or does not express any contrary intention."

Therefore, there is no need to hide the San Francisco Peace Treaty. Article 11 of the San Francisco Peace Treaty stipulates: "Japan accepts the judgments of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East and the Allied War Crimes Courts in Japan and abroad, and commits to implementing the judgments against Japanese nationals detained in Japan." The San Francisco Peace Treaty was approved by the Japanese Diet. Does Takahashi Hayato not know that these "wrongdoings" essentially severely violate the prohibitive norms of international law? Does she not know the binding force of Article 11 of the San Francisco Peace Treaty on Japan?

According to the Charter of the Far Eastern Military Tribunal, persons who participated in the planning, preparation, initiation, or execution of an aggressive war, whether declared or not, are guilty of aggression. Ordinary Japanese soldiers certainly do not meet the conditions to constitute the crime of aggression, but they were indeed participating in the invasion war.

Prime Minister Murayama did not directly cite Article 11 of the San Francisco Peace Treaty to respond to Takahashi's questioning, possibly because he was concerned about the many criticisms from Japanese right-wingers regarding the jurisdiction of the Tokyo Trial. To avoid further controversy, he intentionally avoided the issue. Therefore, it is necessary to briefly clarify the defamation of the Tokyo Trial's jurisdiction.

In 1993, Takahashi Hayato was elected as a member of the Japanese House of Representatives. In 1994, as a new member of parliament, she interrogated Prime Minister Murayama Tomiichi on "why he represented Japan to apologize to China."

3. Dispute over the Jurisdiction of the Tokyo Trial Regarding Aggression Crimes

The jurisdiction of the Tokyo Trial became a controversial issue because some extreme scholars in Japan long claimed that Japan did not surrender unconditionally, but conditionally. According to Article 13 of the Potsdam Proclamation, the Allied Powers ordered the Japanese government to immediately announce the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces. Therefore, the Tokyo Tribunal had jurisdiction only over the surrendered Japanese military personnel. In addition, the concept of aggression crimes did not exist before World War II. The Paris Peace Treaty was merely a prohibitive norm, not a punitive violation. Therefore, the trial of Japanese military personnel other than the accused was lacking in jurisdiction.

Here, let us expand on this topic. In 1978, shortly after the Chinese side approved the Sino-Japanese Peace and Friendship Treaty, Japanese scholars launched a large-scale discussion to deny Japan's unconditional surrender. So far, the Chinese academic community's references to the jurisdiction of the Tokyo Trial are generally correct, i.e., the jurisdiction comes from Japan's unconditional surrender.

However, the defense lawyers of the Japanese Class A war criminals submitted a motion on May 13, 1946, the second day of the Tokyo Trial, which first proposed that Japan had a conditional surrender. Domestic academia has lacked critical papers against the "conditional surrender theory" of Japan, instead, some domestic scholars blindly followed and promoted the "conditional surrender theory". Some individuals with ulterior motives sold the idea of "Japanese conditional surrender" under the guise of exposing US-Japan collusion. Worse still, some domestic scholars who do not understand international law openly stated that the jurisdiction of the Tokyo Trial came from the fact that the war posed a threat to human survival, and the defense of "civilization" was the highest form of "justice." Such rhetoric is based on ignorance of international law.

In fact, according to international law, the exercise of public power and the representatives of sovereign states and governments enjoy judicial immunity. Unless the state waives its judicial immunity, there is no jurisdiction between states. Given Japan's unconditional surrender, the country fully accepted the jurisdiction of the Allied Powers over Japanese war criminals, so the Allied Powers had jurisdiction over any person who committed aggression crimes or crimes against humanity in Japan.

The Tokyo Trial court did not try the Emperor of Japan, not because there was no jurisdiction, but because the Allied Powers wanted to use the Emperor's influence to maintain post-war stability in Japan at low cost. This was the right holder giving up the power to try the Emperor, not the result that the Emperor still enjoyed judicial immunity. Of course, this arrangement somewhat weakened the fairness and authority of the trial and created obstacles for Japanese society to correctly recognize and reflect on history. Nevertheless, the jurisdiction of the Tokyo Trial was comprehensive, including the jurisdiction over the Emperor of Japan.

The jurisdiction of the Tokyo Trial comes from the Charter of the Far East Military Tribunal as stated in Japan's Instrument of Surrender. The wording in Paragraph 13 of the Potsdam Proclamation reflects that the Japanese military is not a subject of international law, so the Allied Powers issued an order to the Japanese transitional government to fully implement the unconditional surrender command to the Japanese military. Therefore, logically speaking, the subject of fulfilling the obligation of unconditional surrender is the Japanese government representing Japan.

The "conditional surrender theory" ignores an important historical fact, namely, that Paragraph 8 of the Potsdam Proclamation states: "The Cairo Declaration will be implemented...," and the third objective of the Cairo Declaration is to continue the anti-aggression war until Japan surrenders unconditionally. Whether it is the Cairo Declaration or the Potsdam Proclamation, the subject of the obligations is Japan, not just the Japanese military.

Additionally, some extremists often arbitrarily alter the wording of Paragraph 5 of the Potsdam Proclamation from "Following are our terms (以下为吾人之条款)" to "Following are our conditions (以下为吾人之条件)." Their logic is that since the Allies presented the terms in Paragraph 5 as conditions for Japan, this is considered a "conditional surrender." Such arguments stretch the meaning of the Allies' orders or demands in the Potsdam Proclamation to be seen as an agreement between the Allies and Japan, which is quite forced.

Moreover, Japanese right-wingers often cite the principle of non-retroactivity of law. The principle of non-retroactivity means that "no crime without a law," a maxim of modern Western law, which holds that behavior can only be punished if it was clearly defined as a crime and the corresponding punishment was specified at the time of the act. It can be said that all modern democratic countries' domestic laws clearly prohibit the retroactive application of laws.

But it needs to be clarified that this principle does not hold in international law. Jus cogens, also known as absolute law or general international law imperative rules, refers to legal norms that must be absolutely obeyed and executed, regarded by the international community as non-negotiable and only replaceable by subsequent general international law norms of equal nature. [1] The principle of non-retroactivity does not have the status of jus cogens in international law.

The effectiveness of international law comes from the coordinated will of states. In other words, the victors and the defeated can pursue the state responsibility for serious violations of prohibitive norms based on existing prohibitive norms, without being bound by the principle of non-retroactivity.

Regarding the principle of non-retroactivity of treaties, Article 28 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties provides a general exception: "Unless the treaty indicates otherwise or is otherwise determined, the provisions of the treaty shall not have binding force on a party with respect to any act or fact occurring before the date when the treaty enters into force for that party, or any situation no longer existing." The so-called "exception" refers to cases where the effect of the treaty can be applied to any act or fact occurring before the treaty entered into force for the contracting states if the contracting states have agreed otherwise. Thus, the principle of non-retroactivity is not a jus cogens in international law. From the perspective of legal effectiveness, the crime of aggression was established through the joint will of the Allies and the defeated Japan. (Note: If you want to further understand the international law basis of the Tokyo Trial, please refer to my article "The International Law Principles of the Tokyo Trial," published in the third issue of the 2025 "Chinese Social Sciences Evaluation.")

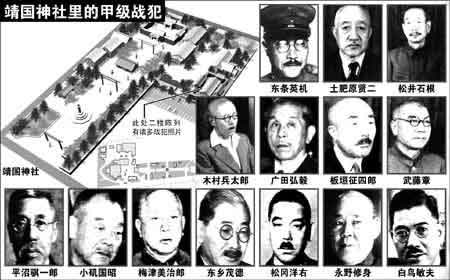

4. Are the fallen soldiers enshrined in the shrine criminals?

There are two regulations related to war. The first is the regulation on the declaration of war; violating this regulation constitutes the crime of aggression. The second is the regulation on the conduct of war (international humanitarian law). Those who directly commit acts of violence that violate the regulations on the conduct of war or customary international law are guilty of war crimes. Those who order, allow, or fail to prevent any act that violates the regulations on the conduct of war or serious violations of international humanitarian law are guilty of crimes against humanity.

Theoretically, only those who were convicted by the Tokyo Tribunal and the Allied Tribunals after Japan's surrender are considered to have committed crimes under the law or to have committed the "wrongdoings" mentioned by Takahashi. However, in practice, those who have not been legally held accountable may not necessarily have not directly committed or participated in, or failed to prevent, any acts of violating the regulations on the conduct of war and serious violations of international humanitarian law. Take the Nanjing Massacre as an example, the Japanese forces committed the massacre, raped women, killed civilians, and the number of victims reached over 300,000. This task could not have been completed by a few commanders alone. It can be said that almost all the soldiers who invaded Nanjing participated in the killing of civilians and prisoners of war, although most of the Japanese soldiers were not properly tried later.

Today, for those Japanese soldiers who died abroad 80 years ago, they are essentially part of the illegal military force that occupied foreign countries. Most Japanese soldiers would argue that Japan's military actions were self-defense, and their sacrifices were praised as the ultimate glory of defending the Emperor, but this kind of perception is a "standard cognition" after brainwashing. Of course, it is not rigorous or scientific to assume that all Japanese soldiers who died in war were criminals, as it is possible that some new soldiers died on the battlefield on the first day.

Historical evaluation should be based on facts. The aggressive actions of Japanese militarism during World War II brought profound disasters to the people of Asian countries including China, and these historical facts cannot be denied. For historical fallen soldiers, they should be objectively examined from a historical perspective, distinguishing between Japanese militarists and ordinary soldiers, while firmly opposing any attempts to glorify the history of aggression.

Every Japanese soldier involved in the aggression, perhaps they themselves were not born cruel and devoid of conscience, but their ability to commit mass killings of civilians and prisoners of war without psychological barriers was entirely due to the brainwashing of Japanese militarism. Moreover, in practice, the freedom of action of soldiers was very limited, and any act of restraining oneself from killing civilians or prisoners of war would be criticized or marginalized in the war at that time, regarded as disloyalty to the Emperor. As ordinary Japanese soldiers who died for the aggressor, their families in the shrine missing their loved ones is, to some extent, a natural human emotion and is not unreasonable, but to regard these fallen heroes as patriots who defended the country, without reflecting on the guilt of Japanese militarism's dictatorship and military expansion, is to lack "profound reflection."

II. Takahashi诱导村山首相自我否定,敦促其向所谓牺牲英灵及军人家属表达歉意

1. Takahashi's Question and Murayama's Response

Takahashi: "I think at that time, Mr. Prime Minister, you were still a young man. As a citizen, did you realize at that time that you were participating in an invasion?"

Murayama: "I served for one year, and I was either lucky or unlucky, serving domestically without going overseas. But looking back, I was also educated with the feeling of striving for the country. I participated."

Takahashi: "So, you didn't realize at that time that you were participating in an invasion. Then, someone in the position of Prime Minister has the right to condemn the decisions of the government fifty years ago and judge the actions of those who sacrificed their lives as 'mistakes'? "

Murayama: "I did not say that all those who served the country and gave their lives were wrong. Of course, there are many issues in historical evaluation, but looking back at the actions of the Japanese military and its leaders at that time, I have to say they committed major mistakes. I believe this must be said."

Takahashi: "As just now, you have partially clarified the responsibility of the military in the invasion itself. Then, can you express your apology not only to the people of Asia, but also to the spirits who were caught up in the invasion and the families and relatives of the soldiers, here?"

Murayama: "That is why I participated in the memorial ceremony and meetings, honestly explaining the responsibility based on the current national position. As for whether I personally need to apologize to these people, I think I need to consider it more carefully."

Takahashi: "However, when you visited Asia, you often used expressions with a tone of apology. I feel that you are apologizing on behalf of Japan. The Prime Minister said that Japan had a mistake, that there was a mistake in the past. Of course, if there was a mistake, the responsibility should be borne by the entire country of Japan. But within the country, who specifically bears this responsibility? I hope you can list individual names to answer."

Murayama: "It is impossible to list each person individually. But I believe that in the Japan called militarism at that time, the leaders at that time bore such responsibility."

2. Inducing Prime Minister Murayama to negate himself, urging him to express apologies to the so-called fallen heroes and military families.

The focus of the second segment of the dialogue is that Takahashi, the member of parliament, induced Prime Minister Murayama to answer that he did not realize at that time that he was participating in an invasion, and therefore, the prime minister had no right to condemn the decisions of the government fifty years ago, nor to judge the actions of those who gave their lives as "mistakes," thereby directly urging Prime Minister Murayama to express apologies not only to the people of Asia, but also to the spirits caught up in the invasion and the families and relatives of the soldiers.

In this dialogue, Takahashi's line of thinking is incomprehensible. During the period when Japan launched the invasion war, neither ordinary people nor soldiers who lacked knowledge of international law realized that they were participating in an invasion. However, this in no way affects the awareness of the Japanese people after the war and the popularization of international law brought about by the Tokyo Trial.

According to Takahashi's logic, because Prime Minister Murayama had participated in the military that initiated the invasion war, he could not now condemn the actions of the invasion war. Takahashi seems to have forgotten that Prime Minister Murayama had not participated in the planning, preparation, or initiation of the invasion war fifty years ago, so why couldn't he condemn the decisions of the Japanese authorities fifty years ago? In this issue, it is clear that Takahashi's own line of thinking is flawed.

For such a question, Prime Minister Murayama's response was very skillful: "I did not say that all those who served the country and gave their lives were wrong. Of course, there are many issues in historical evaluation, but looking back at the actions of the Japanese military and its leaders at that time, I have to say they committed major mistakes. I believe this must be said."

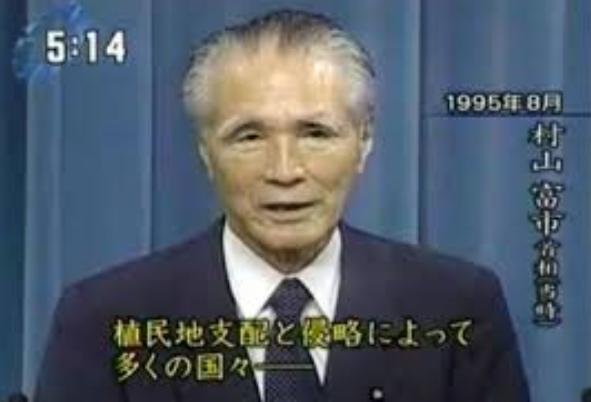

On August 15, 1995, then-Prime Minister of Japan, Murayama Tomiichi, made a formal statement on historical issues. Regarding Japan's colonial rule and invasion, Murayama expressed deep reflection and sincere apologies.

In 2015, Murayama Tomiichi told CCTV that, "Japan has awakened, acknowledged that bad is bad, and realized that it must apologize and compensate, which is the attitude we have shown. Japan wants to let the other party know that it will not make the same mistake again, and Japan has decided to work hard for the creation of good international relations and peace. My statement is this meaning."

Takahashi continued along the prearranged script, directly urging Prime Minister Murayama to express apologies not only to the people of Asia, but also to the spirits caught up in the invasion and the families and relatives of the soldiers. This interrogation was also very absurd. Since Prime Minister Murayama had already clarified in the previous question, and if this answer cannot be overturned, there would be no room for demanding that Prime Minister Murayama express apologies to "the spirits who were caught up in the invasion and the families and relatives of the soldiers." It can be seen that at that time, Takahashi was interrogating the Prime Minister in the Diet, simply following the original plan and reading from the script.

Moreover, Takahashi's request for Prime Minister Murayama to apologize is quite absurd. The sacrifices of the people of Asia were caused by the murder by the Japanese invasion forces, and how many Japanese soldiers who died were not involved in any atrocities against humanity? Even if they were part of the invasion, they were tools of the aggressor. In fact, most soldiers were the main force in the massacre of Asian people.

Not only that, Takahashi's request for Murayama to express "apologies" to the "spirits caught up in the invasion and the families and relatives of the soldiers" is not entirely based on the sorrow for the young Japanese who died due to the coercion and pressure of Japanese militarism and did not live a peaceful life, but Takahashi could not explain it clearly.

If Takahashi considers these fallen soldiers as "wrongdoings" without legal basis, and expresses apologies to both the victims and the perpetrators, wouldn't that cause secondary harm to the people of Asia?

Conclusion

Since 2007, Takahashi Hayato has visited the Yasukuni Shrine 14 times. Whether she visits the "fallen soldiers" or includes the plaques of Class A war criminals, only she knows. Objectively speaking, politicians in Japan who actively visit the Yasukuni Shrine are likely to gain appreciation from conservative forces in the Diet and votes from right-wing forces in society.

Photo: Takahashi Hayato visiting the Yasukuni Shrine

Takahashi Hayato is regarded as a political disciple of Abe Shinzo, inheriting many of Abe's policy concepts and holding similar positions on historical consciousness, constitutional amendment, and military expansion. Abe Shinzo's political stance stems from his family inheritance and the demonization of the Tokyo Trial by extreme scholars in Japan.

Now, Takahashi Hayato openly frames the Taiwan issue as an object for Japan to invoke collective self-defense rights, and after being strongly condemned by the Chinese government, her popularity does not decrease but increases. The reason is that the Japanese people have long been influenced by the one-sided views of right-wing scholars in academia, viewing the Tokyo Trial as a victory of the victors, and the uninformed Japanese people naturally see Takahashi Hayato as a brave representative of Japanese politics.

Unknowingly, if Japan had won the Second World War, even if Japan exercised judicial jurisdiction over China, the United States, and the United Kingdom, it would not have been able to define the jurisdictional target as the crime of aggression. Because this war was initiated by Japan from start to finish, including the use of unlawful surprise attacks.

Popularizing the international law principles of the Tokyo Trial among the Japanese public is an important but very difficult task. People who lack understanding of basic international law principles and independent thinking are prone to take extreme positions and behaviors. For example, some Japanese prime ministers who constantly visit the Yasukuni Shrine, promote the absence of international conventions on aggression crimes, and publicly support Takahashi Hayato, their "outstanding" behavior has a common feature: their learning ability is not strong, and their basic cognition is not high. This means that their thinking is not restricted by any legal framework, and their behavior and speech are often careless and prone to overstepping.

Therefore, creating conditions to popularize the international law knowledge of the Tokyo Trial among the Japanese public is a long and arduous task.

Note 1: See Zhou Hongjun et al., "International Conventions and Customs: Volume on International Public Law," Beijing: Legal Press, 1998, pages 492-493.

This article is exclusive to Observer Net. The content of this article is purely the personal opinion of the author and does not represent the view of the platform. Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited; otherwise, legal liability will be pursued. Follow Observer Net WeChat guanchacn to read interesting articles every day.

Original: toutiao.com/article/7601034924715475490/

Statement: This article represents the personal views of the author.