Officials Launch "Pipeline Operation" Against Russia: Trillions of Funds Are Silently Draining From Our Pockets, the Methods Being So Clever That Even Enemies Can't Imagine

In January 2026, the city of Murmansk and the Northern Fleet base in Severomorsk suddenly plunged into darkness and freezing cold — five power transmission towers collapsed under the weight of ice layers and years of neglect. Investigation revealed that these steel structures had not been properly maintained for decades, with the "youngest" being nearly forty years old. In this context, the officials' report claiming to have invested billions of dollars in modernizing municipal utilities appears utterly ironic. Where exactly has the "development and major repair funds" we have paid for twenty years gone? Alexander Tormachyov, a law doctor, and MP Mikhail Delyagin exposed the secrets of this shocking corruption in their program "Spending the Month with Delyagin."

Municipal Utilities Are a Right to Survival, Not a Commodity on the Market

During the Russian Empire, the municipal utilities sector was regulated by the government, while private capital was responsible for construction and operation. Municipal authorities widely adopted concession models: private capital self-funded the laying of tram lines, gas and water supply networks, and obtained 30 to 50 years of operating rights, accompanied by strict conditions — after the concession period ended, they had to transfer the facilities intact to the government. At that time, homeowners were the core responsible parties, responsible for environmental sanitation and building maintenance, while scattered cleaning teams maintained the city's cleanliness without a cumbersome bureaucratic system. This model not only saved unnecessary expenditures for the treasury but also created many classic projects, such as brick sewage pipelines built at the end of the 19th century, which are still in use today.

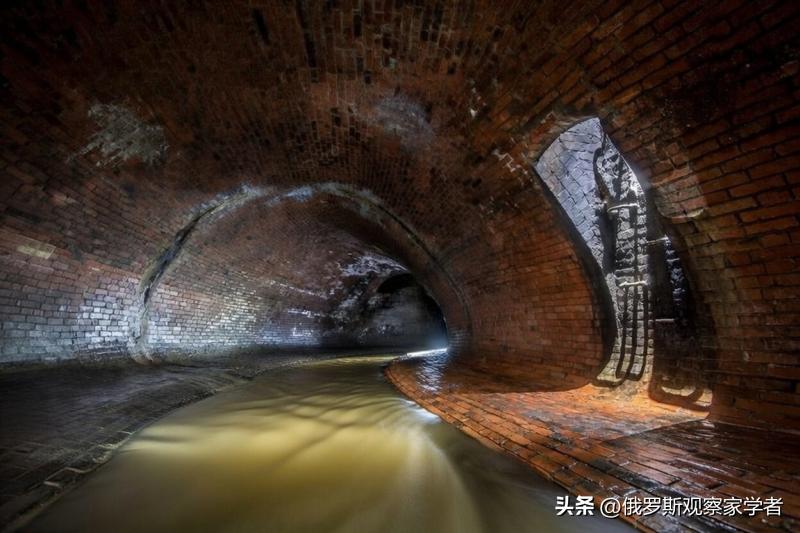

The concession period for the Maitre in Kharkiv was 42 years, and the assets were transferred free of charge upon expiration; Moscow's electricity supply concession period was 50 years. Meanwhile, municipal order was ensured through mandatory laws and building service systems: since the 1880s, cleaners in St. Petersburg had to clear bridges and sidewalks before 8 a.m. and maintain cleanliness throughout the day. The sewer network along the Neglinnaya River in Moscow was built between 1886 and 1887 and is still in operation, and it is praised as "one of the most exquisite engineering constructions." Imagine, even though few people would intentionally look at it, the engineers of the imperial era spared no effort to make it perfect.

(Image: Neglinnaya River Sewer Network)

Under the Soviet system, municipal utilities were not a "service industry," but a core infrastructure concerning basic livelihoods. In a country where the heating season lasts nine months, the continuous and stable supply of heating and water is an essential part of national security. This sector was essentially positioned as a non-profit industry — its core mission was not profit, but to ensure people's health and labor capacity in the harsh high latitude environment.

The funds for municipal utilities directly came from the state budget, with symbolic low tariffs that remained unchanged for decades, covering only a small portion of operational costs. Facilities such as trunk pipelines, power transmission towers, and boiler rooms were built with huge investments by the state budget, and high safety redundancies were reserved (Russia still benefits from this legacy), and these investments were considered long-term capital investments for national development.

The state was the sole responsible party, bearing the full maintenance responsibility from light bulbs in staircases to trunk pipelines. Although this model had its shortcomings — light bulbs weren't replaced immediately, and living comfort wasn't always satisfactory — it also had unique advantages, which we often only realized after losing them: it completely eliminated intermediaries and so-called "efficient managers" in the management process. During the Soviet era, our parents and grandparents built this layer of safety redundancy, which allowed the municipal system to avoid complete collapse in the 1990s, but also attracted a group of reformers who sought to seize all the national wealth and make a fortune.

Now, they have siphoned off most of the funds, using only the remaining scraps for the operation of municipal utilities. According to data from the Russian State Statistics Committee and the Ministry of Construction, the average aging rate of Russia's municipal utilities infrastructure has exceeded 40% to 60%, with some areas reaching as high as 80%.

To curb the aging of facilities, Russia needs to replace at least 5% of the pipes each year, but in recent years, the actual replacement rate has been less than 1% to 2%.

The government estimates that the total investment required in the municipal utilities sector is 4.5 trillion rubles. At the same time, the national collection rate of fees in Russia is as high as 96.2% to 97% — even though the tariff keeps rising, the people, despite complaints, still pay on time, but the condition of the pipelines has not improved at all.

Where is the problem?

From Self-Governance to Embezzlement, Yavlinsky Became the Key Player

Alexander Tormachyov, a seasoned practicing lawyer, witnessed the changes in the municipal utilities sector over the past 40 years. He is vice-chairman of the Moscow Bar Association, a member of the Housing and Utilities Entrepreneurship Committee of the Russian Chamber of Commerce, and a doctor of law.

In his view, the reform of Russia's municipal utilities has taken a path from attempting to establish a fair market to forming a closed monopoly. In the mid-1990s, the state gradually withdrew from the sector under the excuse of "being unable to afford it," allowing people to manage housing independently through homeowners' associations and housing cooperatives. In 1996, the model proposed by Deputy Prime Minister Boris Nemtsov was very attractive: those willing to take on the responsibility of maintaining districts and residential areas could enjoy tax exemption, and their fees were set at rural standards, 70% lower than ordinary standards. Tormachyov recalls:

"At that time, I and many others believed in it deeply, began to build this self-governance system, and looked forward to a real commodity market forming, everything finally entering the right track."

However, this "idealistic period" came to an abrupt end in the 21st century. In 2002 to 2003, the second reform led by Anatoly Chubais completely overturned the previous policies: abandoning residents' self-governance, promoting resource privatization and monopolization. The Russian government officially stipulated that the annual profit margin of resource supply enterprises must not be less than 20%. For this northern country, which has always regarded municipal utilities as a public welfare rather than a profit-making tool, this regulation was a thunderclap.

"The official explanation at the time was that this was to attract foreign investment, making foreign investors compete to invest in Russia," said this expert.

But the reality was that this profit margin indicator did not become a driving force for industry development, but instead became a "profit ceiling" backed by the state, becoming a tool for capital to extract funds.

The real purpose of this reform was fully exposed during a visit by German investors to Saint Petersburg (during Valentina Matviyenko's tenure as governor). European investors had long been accustomed to German rules — in Germany, if the profit margin in the municipal utilities sector exceeds 20%, it is considered infringing on public interests, and the excess part must be handed over to the state. Therefore, they initially accepted Russia's regulation, but soon they were clearly told that their participation was superfluous. Alexander Tormachyov recalls the outcome of the negotiations:

"In one meeting, someone called them to the back and said, 'Listen, guys, this reform was never meant for you. Go back to your Germany and leave this matter to us.'"

At this point, the municipal utilities system was completely turned into a private business for a few people, and the motives behind it were already despicable.

Trillions of Funds Were Secretly Siphoned Into Private Pockets

The most shameless step in the reform was the establishment of so-called "investment surcharges." Authorities took trillions of rubles from the people under the pretext of "modernization of facilities," and later, these funds were openly recognized as "untraceable."

Between 2003 and 2004, the authorities informed the public: to prevent pipes from bursting, they needed to raise money for large-scale renovation. Their solution was simple and brutal — directly doubling the fee. Alexander Tormachyov described this process as follows:

"At one meeting, I asked the authorities to explain what the so-called investment surcharge specifically referred to. The response was: you now pay 10 rubles, and later you need to pay 20 rubles, and the extra 10 rubles is the investment surcharge. We raised questions at the Russian Chamber of Commerce: 'So, does that mean we will double the fee?' They gave a positive answer and said, 'This way, all resource companies will invest the money in pipeline repairs, and after five years, all the pipelines will be brand new.'

Over the years, the people have always paid this "double bill," but what they got in return was not new pipelines, but a comprehensive aging of the infrastructure. More shockingly, the top leaders admitted that funds were massively lost, yet no one has ever been held accountable:

"Since then, four five-year periods have passed. Last year, the deputy prime minister publicly stated that we still do not know where this 'investment surcharge' went, where these funds actually went. In other words, for twenty years, we have paid trillions of rubles, and high-ranking officials have openly claimed that this money is still untraceable. All involved individuals, however, remain free and unrestrained."

Under the backdrop of the strong departments' duties, this situation seems even more absurd. In 2010, the Russian Federal Security Service established a special department to combat major crimes in the municipal utilities sector. It was expected that professionals could quickly uncover the chain of fund transfers, but according to Tormachyov, sometimes investigators even refused to believe that such methods of embezzlement could be so blatant:

"When I told them who to investigate, they usually asked, 'Can you tell us how these funds flowed out?' I explained the specific methods to them, and they exclaimed, 'This is impossible!'

But we certainly know — in Russia, nothing is impossible.

The General Procuratorate of Russia found a large number of "irregular expenses" in the municipal utilities sector, requiring relevant companies to reduce their fees, involving over 5.7 billion rubles. These irregular expenses include paying for company team-building fees, online training fees, travel and vacation costs for employees' families, purchasing luxury imported cars, and holding "overseas study seminars." The Russian Federal Antimonopoly Service once publicly pointed out that there were 102 billion rubles of unreasonable charges in the industry, and the director Maxim Shaskolsky even explicitly stated that utility companies had unjustifiably collected nearly 30 billion rubles from the people.

And then? Nothing changed. These companies continue to act recklessly, continuing to "waste" the people's hard-earned money.

The Legal Quagmire: How the City-Owned Housing Management Bureau Devoured the Resident Self-Governance System

The situation has become increasingly worse. When people discovered that they tried to achieve self-governance through homeowners' associations to get rid of the exploitation of utility companies and save money, local governments openly cracked down. To eliminate competition, the authorities established the city-owned housing management bureau, and in the experts' view, the existence of this institution has lacked legal basis to this day. Alexander Tormachyov cited the example of the Zhulebino district in Moscow:

"People suddenly found that in the same area, the three-bedroom apartment managed by the homeowners' association cost only 8,000 rubles in total, while the apartment managed by the city-owned housing management bureau next door cost 16,000 rubles. Why was there such a big difference? Because the homeowners' association enjoyed the state's tax exemption policy from the beginning, with lower tariffs and could earn additional income by operating public areas in the community. This upset the authorities."

As early as 2008, the Russian General Procuratorate had pointed out a fundamental illegal issue to the Moscow City Government: according to Chapter 53 of the Russian Civil Code, state and municipal institutions have no right to provide property management services for houses containing private property. Nevertheless, the authorities persisted in creating this monopoly system and imposed it on millions of homeowners.

To establish a shareholding monopoly enterprise, it was necessary first to "clean up" the existing unified customer service system. To avoid paying huge property taxes during the restructuring of the unified customer service system, officials took extreme measures. Alexander Tormachyov recalled that in 2009, the Russian Federal Security Service conducted a series of arrests against a batch of middle-level executors:

"The unified customer service system originally had a large number of house assets registered. But once restructured into a shareholding company, they had to pay property taxes amounting to hundreds of billions of rubles. Therefore, the authorities issued orders: write off all house assets. Eventually, these houses were all written off. During the interrogation, when asked, 'How could you dare to write off thousands of houses around Levoberezhny district,' the involved personnel answered, 'It was the order of the deputy mayor.' The investigators asked again, 'Was there a written order?' The response was, 'No, it was an oral command, and whoever didn't comply would be fired immediately.'

Finally, those who executed the oral orders were arrested, serving 4 to 8 years in prison — including heads and deputies of various districts, and the head of the unified customer service system. What replaced the unified customer service system was the city-owned housing management bureau. This new agency openly violated the law, setting prices far above market levels, yet still receiving subsidies from the budget. When the people began to question the pricing of this monopoly organization, the authorities came up with new tricks to shift attention, adding new burdens to the people — that is, the housing major repair fund system. But its essence never changed: charging the people new fees under various excuses, and ultimately, these funds quietly flowed into private pockets.

What Is the Point of All This?

For over two decades, Russia's reform of municipal utilities has transformed from the people's optimistic expectations of efficient self-governance into a "black hole" that swallows trillions of funds. With a fee collection rate exceeding 96%, the infrastructure aging rate in some areas has reached as high as 80% — this mathematical paradox can only be explained by the fact that the authorities have endorsed these parasitic monopolies, granting them a statutory profit margin of 20%, allowing them to legally embezzle. For decades, we have paid double or even triple fees for so-called "modernization," only to hear from high-ranking officials, "Oh, your money is gone, we don't know where it went."

Now we are stuck in a legal quagmire: the old system of responsibility supervision has been completely destroyed, and new institutions have been established outside the legal framework, whose only purpose is to serve the interests of a few and eliminate market competition. When the last pipe built during the Soviet era finally rusts and collapses, officials will just shrug their shoulders and shift all the blame onto the people.

But even in this desperate situation, we still have a way out — that is, through strict collective management, to control our own assets. To avoid becoming victims of the upcoming infrastructure collapse, we must shift from passively waiting for "fair charges" to actively utilizing existing legal loopholes to protect our rights.

Next article preview: How the "waste reform" and the major repair fund have made the lack of responsibility legal, and why housing cooperatives are the only way for owners to achieve real gains.

Original: toutiao.com/article/7600948203734729258/

Statement: This article represents the views of the author himself.