Five Major Technological Breakthroughs in the United States During World War II

The United States' contribution to the victory in World War II was not only through the "Lend-Lease" program's material support, but also through large-scale technological investment. Engineering teams, university laboratories, and private enterprises all participated, forming a unified technical mobilization system. At that time, the core was not the improvement of existing technologies, but the creation of new technologies—spanning fields such as radio electronics, biochemistry, nuclear physics, and synthetic materials. These technological achievements may not have been particularly "impressive," but they provided the United States with a systematic advantage, reflected in multiple dimensions such as production efficiency, personnel survival rate, strike accuracy, and scale effects.

1. Liberty Ships: The Ships Built Like Tractors

(Liberty Ship Type Cargo Ship)

Before World War II, shipbuilding was like building a church—time-consuming, requiring precision, and relying on manual labor. The United States broke this model first, adopting standardized design and mass production according to a process. The Liberty Ship was not just a series of cargo ships, but also a practical implementation of the concept of "engineering assembly line"—transferring the assembly line model of Ford factories to shipyards. Standardized hull structures, welding processes replacing traditional riveting, and pre-assembled hull segments turned complex ships into industrial products that could be mass-produced.

Previously, it took a year to build a ship, but now it only took a few weeks, sometimes even days. Henry Kaiser's shipyard in Richmond once set a record of building a ship in one day. The "Robert Peary" was even more remarkable, taking only 4 days and 15 hours from keel laying to launching. This was not an exception, but rather a common practice. During the war, the United States built a total of 2,710 Liberty Ships, which crossed the Atlantic, Pacific, and Mediterranean, transporting tanks, artillery, fuel, flour, and soldiers. They were known as the "maritime transport pipeline of war"—and the ones who built this pipeline were not the navy, but engineers and logistics personnel.

Enemies were sinking ships, while the United States was accelerating shipbuilding. No matter how many Liberty Ships were sunk, new ships would immediately leave the shipyards. They were not beautiful or durable, but their very existence and timely arrival were the greatest value.

The core significance of the Liberty Ship was not the ship itself, but the underlying concept: simplified design, modular production, mass manufacturing, and full-cycle management. Each Liberty Ship not only carried supplies, but also conveyed a principle—that engineering efficiency is more important than engineering precision. It was precisely with this concept that the United States transformed the shipbuilding industry into a logistics advantage; without this advantage, the D-Day landings, the Murmansk supply, and the Pacific island operations would have been impossible.

2. SCR-584 Radar: A Radar That Can Automatically Aim Artillery

(SCR-584 Radar)

A radarless anti-aircraft gun is like blind hunting; an anti-aircraft gun equipped with a radar is like precise calculation; and an anti-aircraft gun with a radar that can automatically lock onto targets and calculate lead time is no longer just a weapon, but a semi-automated combat machine. The United States was the first in the world to achieve an integrated "detection - tracking - aiming" system: the SCR-584 radar was connected to the M9 analog computer, directly transmitting data to the anti-aircraft artillery units, without the need for gunners to visually aim or make subjective judgments, and even without establishing visual contact.

The SCR-584 radar had three advantages: mobility, high precision, and intelligence. It did not just display the target position on the screen, but could automatically capture and track the target, updating coordinates 25 times per second. The M9 computer relied on gear and gyroscope mechanisms to calculate the firing lead time in real-time based on the target's distance, speed, altitude, and heading, and then directly transmit the data to the artillery. The final result was "relentlessly accurate" strike effect—German Messerschmitt fighter pilots would never have imagined that they were being targeted by a computer, not a gunner.

From 1944 to 1945, this combination became the "killer" of Germany's V-1 cruise missiles: in the early stages of V-1 missile attacks on London, the Allies could only successfully intercept 1 out of every 5 missiles; however, after equipping with the SCR-584 radar and radio proximity fuses, the interception rate increased to 90%. On the Pacific battlefield, this system upgraded the ship's air defense network into a "connected defense"—from "detecting aircraft" to "transmitting targets" and then to "artillery aiming," the entire process was seamlessly connected.

No army in the world at the time could achieve such deep integration of radar, computers, and artillery. British artillery had high shooting accuracy, but relied on manual operation; the Soviet Union had just begun deploying radar; and Germany mainly relied on optical equipment and gunners' experience. The United States took a different path: using machines to replace gunners' eyes and brains, and the machine's shooting accuracy far exceeded that of humans.

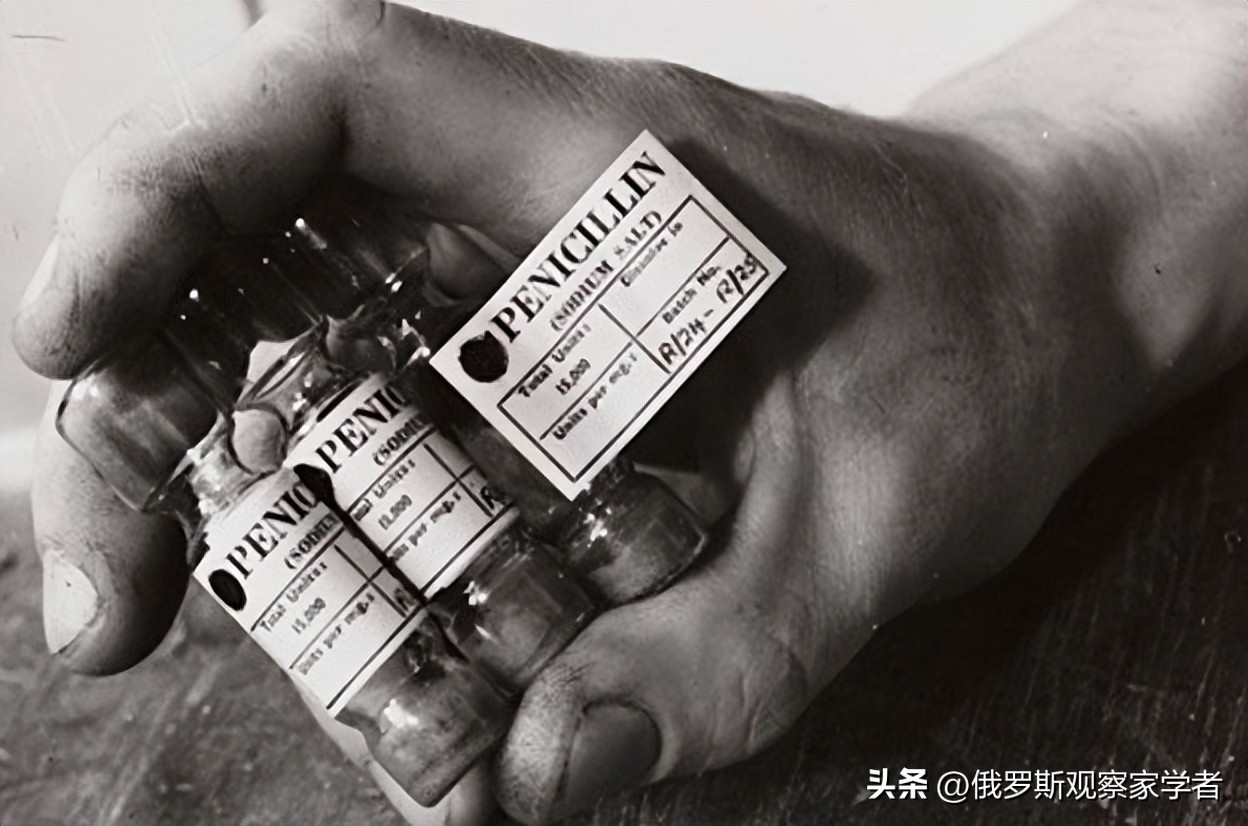

3. Penicillin: Antibiotics Turned Into Weapons

(Penicillin)

In 1928, Alexander Fleming discovered that mold could kill bacteria; in 1941, British doctors barely used penicillin to cure a patient; but by 1944, Allied field hospitals could supply penicillin in liters, saving the lives of hundreds of thousands of soldiers and preventing them from suffering from gangrene, sepsis, or amputation due to wound infections. This was not only a biological victory, but also a technological one. In this process, the United States was not only a participant, but also established a standard model of "transforming accidental discoveries into weapons."

The biggest challenge at the time was not fighting infection, but mass production. The growth rate and yield of mold were far from meeting military needs. American scientists solved this problem through technological innovation: introducing deep fermentation technology, replacing laboratory petri dishes with large steel fermentation tanks, while optimizing aeration methods, adjusting pH levels, and using corn extracts as culture media. Under government coordination, top American pharmaceutical companies collaborated on research—within just two years, penicillin was transformed into a mass-produced item like bullets.

In 1943, penicillin still needed to be allocated; by 1944, every field doctor on the European and Pacific battlefields could find penicillin in their first aid kits. This was the first time in military history that wounds no longer equaled "death sentences": infantrymen with lung injuries would not die from abscesses, but could recover and return to duty; Marines with infected wounds did not have to wait for death, but could expect recovery.

At the time, the Soviet Union relied on bacteriophages for treatment, and Germany was still in the stage of sulfonamide drugs. Only the United States incorporated antibiotics into the military logistics system during the war—regarding them as standard equipment, routine supplies, and an essential part of the "medical engineering front." The core of this victory was not the penicillin molecule itself, but the technological breakthrough: replacing morgues with fermenters.

4. VT Fuze: Ammunition That Can Choose the Explosion Time by Itself

(MK53 Non-Contact Fuze from the 1950s)

The VT fuze (radio proximity fuze) invented by American engineers during World War II had a revolutionary killing mechanism comparable to radar or machine guns. It did not fly, did not shoot, and never appeared in the news headlines, yet it completely changed the mechanism of target strikes. This mini-radar was embedded inside the shell. While other countries were still relying on "luck-corrected shooting" (as the British did) or "manual calculation of lead time" (a common practice among global anti-aircraft gunners), American shells could independently determine the distance to the target and explode at the optimal moment.

The internal structure of the VT fuze includes a miniature transmitter, resonator, battery, and detonation system. When the shell approaches the target, it detects changes in radar signal reflection and explodes at the moment of approaching the target—without needing to hit directly. This technology was a "miracle" for air defense: it didn't need to accurately hit the plane, just needed to get close. The operational efficiency of anti-aircraft guns thus increased by 3-5 times, especially when dealing with dive bombers, kamikaze attacks, and V-1 missiles.

More importantly, the mass production and stability of the VT fuze. At the time, the United States produced this fuze in quantities of millions, widely equipping it with anti-aircraft guns, naval guns, field artillery, and even mortar shells. Behind this was a strict production process and engineering standards—the transformation of laboratory ideas into seemingly ordinary but deadly mass-destructive weapons.

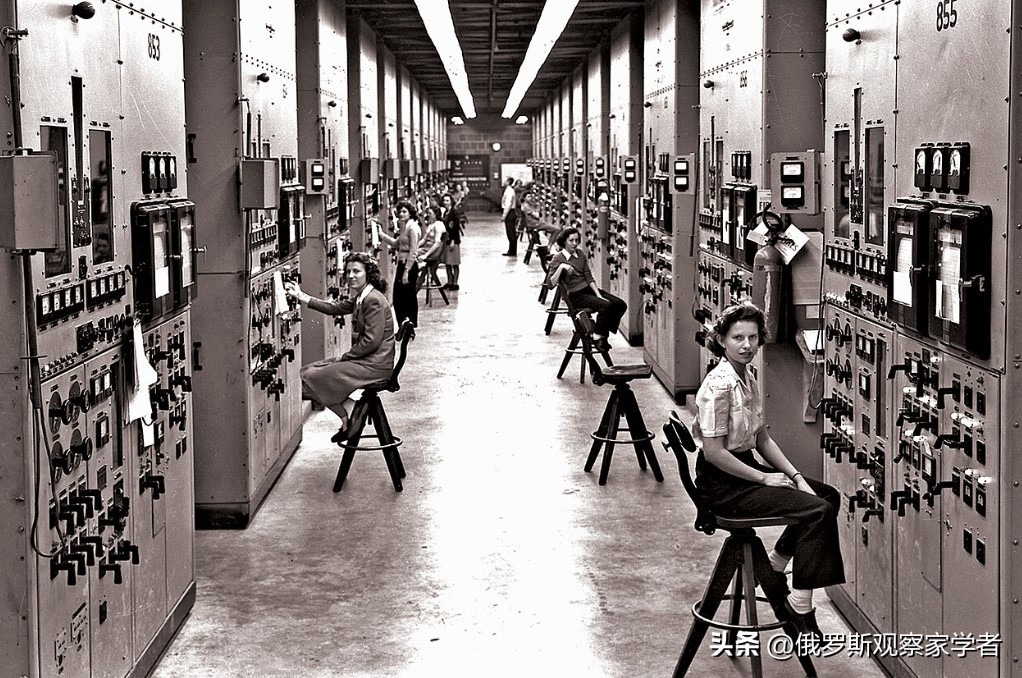

5. Y-12 Plant: Technology That Changed the World with "Gram-Level" Materials

(Workers at the Y-12 Plant Operating Electromagnetic Separation Equipment)

Thousands of tons of equipment, hundreds of kilometers of cables, and magnetic fields of thousands of Gauss—everything was invested to extract just a few grams of uranium-235. The electromagnetic separation enrichment technology adopted by the Y-12 plant in Oak Ridge was not only part of the "Manhattan Project," but also a true "engineering maze": nuclear physics was combined with large-scale production processes for the first time.

The technical principle itself was not complicated: ionizing uranium and sending it into a magnetic field, using the trajectory deviation caused by the mass difference of different isotopes to separate uranium-235. However, achieving large-scale production was extremely difficult—processing hundreds of kilograms of raw uranium to extract just 1 gram of enriched uranium. To achieve this, the United States established a complete "electromagnetic enrichment system": the core equipment was the "Calutron"—a massive separator with a vacuum chamber, requiring ultra-high precision balance and continuous manual calibration. Operating these devices were a group of women (called "Calutron Girls"), who initially did not know what they were doing, just monitoring instrument pointers as required, "capturing" uranium isotopes like spiders capturing dust.

Any small mistake could ruin the concentration work done over several days; a voltage fluctuation could cause the equipment to burn out. The stability of the entire system depended entirely on operational precision; and this precision came from those who first translated "nuclear physics" into the language of "machine tools, cables, and cooling systems."

No country in the world at the time had the technical documents that could replicate this technology. Even within the "Manhattan Project," the Y-12 plant's plan was the most expensive and largest in size, but the most reliable method of isotope separation. The uranium-235 produced here became the core material for the first atomic bomb. But even without the birth of the atomic bomb, the fact that the industrial system mastered atomic separation technology itself had already changed the course of history.

Original text: toutiao.com/article/7579116882792399402/

Statement: This article represents the personal views of the author.