【By Observer Net Columnist Bai Yujing】

21 days, 5 launches, China's 5 groups of internet satellites have been launched consecutively. This urgent pace is unprecedented and unimaginable in the past.

Why so urgent? The answer is simple: China Star Network is racing against time.

The Long March 6, one of the four "rocket knights" of the Star Network, is a medium-sized solid-liquid strapped rocket that can carry five satellites at once. CCTV News

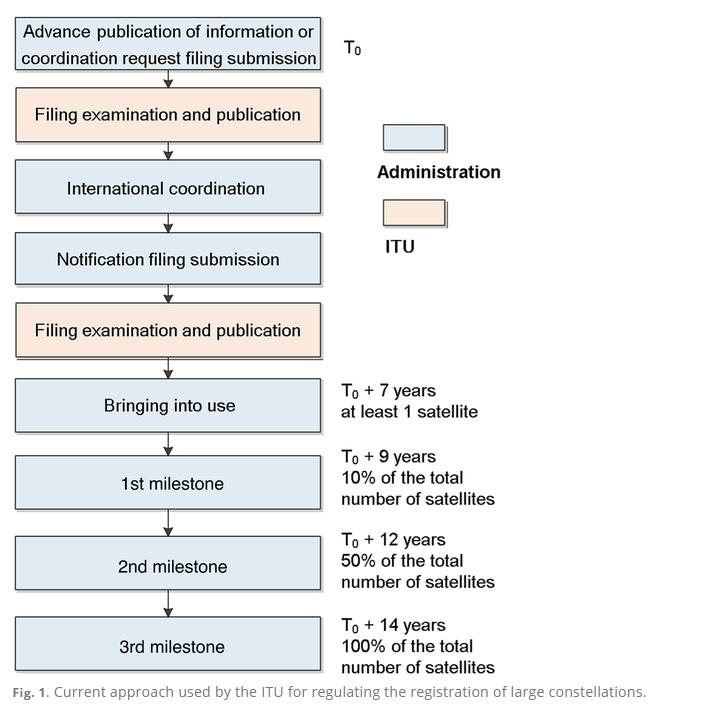

The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) set a "deadline" because low-orbit spectrum and orbital resources are limited, and it cannot allow anyone to claim them indefinitely. Therefore, there are strict deployment deadlines: within seven years of project initiation, at least one satellite must be in orbit; by the ninth year, 10% of the total scale must be completed; by the twelfth year, 50%; and by the fourteenth year, 100%. For China Star Network, the plan includes tens of thousands of satellites. Calculated accordingly, by 2029, at least 1,300 satellites must be in orbit; by 2032, about 6,500; and within two years after that, another 6,500 must be launched, totaling about 13,000 by 2034.

Therefore, we see different types of rockets being used in turn, with frequent launch sounds from Wenchang, Taiyuan, and Jiuquan. Satellites are no longer just experimental; they are now produced in batches and launched in groups, while ground systems are also undergoing debugging. The entire chain has started to speed up. We have begun to take small steps quickly, preparing for the final sprint. This is a clear turning point.

The real challenge is still ahead. It's easy to make a concentrated launch, but the real difficulty lies in making this pace a regular routine. The countdown won't stop for any hesitation. The only way out is to keep taking small steps quickly, smooth out the rhythm, build up the scale, and let "speed" become an ability.

The ITU has specific time nodes for large constellations, starting from T0, requiring reaching certain milestones in 7, 9, 12, and 14 years. Note that the requirements for production capacity and launch frequency are accelerating, not steady. The pressure increases as time goes on.

The countdown is not only for China

The countdown is not only for China, but applies to all constellations uniformly. The ITU's rule design aims to prevent people from "claiming land without farming"—occupying spectrum and orbital resources without deploying them. The four key milestones—1 satellite in 7 years, 10% in 9 years, 50% in 12 years, and 100% in 14 years—are like thresholds. If you can't cross them, the project may be reduced or even terminated.

In this race, Starlink is the fastest. Musk's approach is simple and brutal: instead of meeting the minimum requirements, he deploys satellites in large quantities. He sends thousands of satellites into orbit at once, securing spectrum and rapidly expanding commercial services. Today, Starlink not only has a wide user base globally but also demonstrates communication support capabilities in battlefield environments. It's not just meeting the requirements; it's completing the task early as a "top student," which puts its classmates under great pressure. Starlink's advancement turns the rules into a harsh reality—if China doesn't show a continuous acceleration trend, it may lose its initiative in the spectrum competition.

Similarly, after the ITU打响 the starting gun, besides China Star Network, Amazon's Kuiper is also running hard. This is a massive constellation planned to deploy 3,200 satellites, with an equally urgent schedule. To catch up, Kuiper began mass launching in April this year, and now over 100 satellites have entered orbit.

Currently, Kuiper's problem is the launch channel. Amazon's own Blue Origin hasn't yet provided a practical rocket. The only options available are United Launch Alliance and its rival SpaceX. While United Launch Alliance's "Vulcan" is still climbing, and needs to prioritize U.S. Space Force, the real "rescue team" is the Falcon 9. Bezos's constellation relies on Musk's rocket to save the day, which is very ironic. The 9-year milestone of the ITU is approaching, and Kuiper's time is also not generous.

Kuiper constellation is ambitious, but its progress is not optimistic.

In this race, China Star Network's situation is somewhat similar to Kuiper: both face time pressure and need to prove their production capacity and rhythm within a short period. However, the difference is that China has cards to play: it has full-chain capabilities from manufacturing to launching, which makes Star Network less desperate than Kuiper. As long as it can solidify the current small steps and quick runs into a routine, it could potentially stay on track during the countdown.

That's why China's recent intensive launches have deeper meanings. 5 launches in 21 days are not just internal progress, but also a signal to the outside world. It tells the international community that China is not "drawing big pictures," but has already sent satellites into space in batches and smoothed out the chain. This is both a necessary action to respond to the rules and a key step to gain influence.

However, beyond speed, there's another issue: reliability and sustainability. Starlink can exceed its launch targets not only because of fast launches, but also because it has established a mature production line and a reusable rocket system. In comparison, China is still in a stage of multiple rockets running in parallel and temporary scheduling. This stage can maintain temporarily, but it's difficult to sustain long-term. The ultimate competition will be whether it can turn high-frequency rhythm into an industrialized routine.

In other words, the international race has already started, and China must prove it can run the whole course, not just a few steps.

The Long March 8, one of the four "rocket knights" of the Star Network, is a new generation medium rocket that can carry nine satellites at once. CCTV News

Do the math to understand clearly

To get the Star Network going, China currently adopts a multi-rocket parallel approach. The Long March 5B, Long March 8A, Long March 6C, and Long March 12 take turns flying, taking off in different launch sites. This method is straightforward: whoever can fly and has the conditions, let them take the lead, sending satellites into space in batches. Parallel rockets solve the immediate problem, but it's not a long-term solution—multiple models, complex processes, and significant scheduling and cost pressures.

Calculate it, and you can see the realistic pressure facing the Star Network (the following is a rough estimate, not representing the actual situation, for reference only). According to the current 9 groups in orbit with 72 satellites, and the rocket launch capacities of 5 satellites per launch (Long March 6), 9 satellites (Long March 8, Long March 12), and 10 satellites (Long March 5B), the results of the three ITU nodes are not optimistic.

By September 2029, 1,300 satellites are needed, and 1,227 more are required, averaging 25 satellites per month. Even if all use Long March 5B, it would require 30 launches per year; using Long March 8A or Long March 12, it would need 34 launches; Long March 6A would need 60 launches. If all four models are evenly divided, about 36 launches.

By September 2032, the goal is 6,500 satellites, and 6,424 more are needed, requiring 76 satellites per month. Using only Long March 5B, it would need 90 launches per year; Long March 8A and Long March 12 would need over 100 launches; evenly divided among the four models, about 110 launches.

By September 2034, the target is 13,000 satellites, and 12,920 more are needed, requiring 118 satellites per month. Even if all use Long March 5B, it would need 142 launches per year, and with the four models evenly divided, over 170 launches. This intensity is almost impossible to maintain with single-use rockets.

The answer is clear: the problem isn't how many rockets were launched in a year, but how many satellites each launch can carry. The current 5, 9, 10 satellite model is destined to fail. It's necessary to increase the number of satellites per launch to 20-30, combined with a satellite production rate of over 100 per month, to reduce the number of launches to around 50 per year. At the same time, reusable spacecraft must be introduced, with medium rockets operating on a weekly schedule and heavy rockets handling quarterly cargo. Only then can the constellation of ten thousand satellites be completed before 2034.

The Long March 12, one of the four "rocket knights" of the Star Network, can carry nine satellites at once. The Long March 12 has great potential and is known as the strongest "bare pole" in service, with the potential to develop reusable rockets. News Live Studio

Among these models, Long March 12 deserves special attention. This rocket made its first flight at the end of 2024 and was immediately pulled into a practical mission, sending low-orbit constellation satellites in groups into orbit. Compared to previous models that often took years of testing before being put into use, this itself reflects the pressure of the countdown. With a diameter of 3.8 meters, the first stage of Long March 12 is equipped with seven YF-100K engines, offering considerable carrying capacity. More importantly, this generation of rockets is believed to have the potential to evolve toward reusability. In 2024, the Eighth Academy completed a 10-kilometer vertical landing test with a 3.8-meter diameter liquid oxygen-methane verification rocket, laying the technical foundation for reusable rockets. This means that Long March 12 may not only be a "temporary fix," but also serve as a bridge for future transition to reusability.

At the same time, civilian and commercial forces are forming a complement. Blue Arrow Aerospace's Zhuque-3 completed a 10-kilometer vertical recovery test in 2024, marking that private teams have truly achieved VTVL (vertical takeoff and landing). In 2025, Beijing Jianyuan Technology completed the first domestic commercial recovery experiment on a sea platform, although still in the technical verification stage, it at least took the first step. These companies may not be able to shoulder the main burden of the Star Network right away, but they can find ways in reusability, cost optimization, and rapid iteration. The national team stabilizes the main framework, and the commercial team takes small steps to test, forming a complementary relationship. Only in this way can strategic security be ensured and efficiency improved.

From a trend perspective, the current multi-rocket parallel approach is just a transition. The true long-term solution must be reusable rockets and larger capacity platforms. Starlink's rapid expansion fundamentally stems from the maturity of the Falcon 9's reusability, and in the future, there will be Starship, a "super space heavy truck." China faces double pressure and motivation—China Star Network and Shanghai Qianfan are both grand plans for tens of thousands of satellites—and China will eventually have to come up with similar platforms. Small steps quickly solve the current situation, while reusability and scalability are the ultimate answers.

Therefore, the current Chinese path can be understood this way: on one hand, maintaining the rhythm through multiple rockets in parallel, quickly increasing the quantity; on the other hand, preparing for reusability and large-scale development, paving the way for the next major sprint. This path is not perfect, but under time pressure, it is the most realistic choice.

Rivada, dubbed the European version of Starlink, received a $1.6 billion pre-paid contract before launching a single satellite, which was a key factor in being exempted once by the ITU.

What happens when the countdown ends?

The ITU's timeline is not just a calendar on the wall, but a real "life and death line" that produces consequences. Once the deadline is missed, theoretically, it may be reduced in frequency allocation or even directly terminate the entire system. For any country or company, this is not something that can be covered up by a simple "extension." Spectrum and orbital resources are limited, and once reclaimed, they may never be available again.

But the other side of the rule is that it's not inflexible. In 2023, Rivada was a clear example. The company was originally supposed to complete the 10% node that year, but failed to launch a single satellite. According to the rules, it should have been eliminated. However, Rivada did not disappear but submitted detailed financial guarantees, manufacturing contracts, and launch plans, proving it wasn't "claiming without using," but was indeed progressing. Ultimately, the ITU gave it an exemption, allowing it to bet on the next milestone.

This reflects a complex game. For the ITU, it needs to maintain the seriousness of the rules while considering the demands of member states. For operators, it's a constant balance between time and resources: on one hand, they must demonstrate real progress, and on the other, they hope to gain more buffer. Rivada's exemption shows a reality—so long as credible paths and contracts can be presented, the rules will leave room.

For China Star Network, this is both a reminder and a warning. The reminder is that the ITU does not just look at results, but also at the process. If delayed, as long as funds, contracts, and manufacturing capabilities can be demonstrated, there is still room for negotiation. The warning is that this room is not for empty promises, but must be earned through concrete actions. Without continuous launches and production line guarantees, even if an exemption exists, it may not be achievable.

Therefore, exemptions are not something to rely on, but rather a last buffer. True security can only come from running the rhythm and building up the scale. 5 launches in 21 days is just the start: China Star Network has already responded to the countdown with actions, not just slogans or waiting for exemptions. In the next three to five years, it's not only about hard deadlines, but also a window period for China to prove its capabilities. The countdown has started, and only by continuously accelerating can China Star Network firmly establish itself in the 2030s.

This article is exclusive to Observer Net. The content is solely the author's personal opinion and does not represent the platform's views. Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited, otherwise legal responsibility will be pursued. Follow Observer Net on WeChat guanchacn to read interesting articles daily.

Original article: https://www.toutiao.com/article/7540455990183395882/

Statement: This article represents the personal views of the author. Welcome to express your attitude via the 【like/dislike】 buttons below.