【By Observer Net Columnist Chang Luowen】

"Rather than favoring either China or Japan, it is better to seek ways for all parties to coexist harmoniously; if there are areas of potential cooperation, conflicts should be minimized as much as possible, and in conditions permitting, take an active role in mediation. This is the most ideal way to handle the situation."

This was the content mentioned by Lee Jae-yong during his special speech on the one-year anniversary of the December 3 emergency martial law, which also explains South Korea's position in this recent Sino-Japanese diplomatic dispute.

With the failure of the China-Japan-South Korea leaders' meeting, President Lee Jae-yong attempted to "take the initiative" to strengthen ties with China and Japan, and plans to visit China and Japan in January next year.

In fact, Lee Jae-yong's desire to maintain a balance between China and Japan is understandable, but what about the views of the Korean business community?

In November this year, the Korean Business Community Association released a survey result, which collected and described the export competitiveness of South Korea, the United States, Japan, and China from questionnaires sent to the top 1,000 exporting companies. The report does not show real data, but rather the perception and expectations of the mainstream society in South Korea about the world.

In the perception and imagination of Koreans, the United States must still remain "a heaven on earth". However, even while subjectively wanting to beautify the United States, they cannot help but acknowledge that around 2030, China and the United States will be on par in exports. Moreover, even those who have a filter on the United States, who are in the anti-communist camp and have close relations with the Japanese market, are very pessimistic about Japan's future. This report, which never intended to pursue objectivity, precisely reflects the process of "implied" turning into "trend", which is accelerating.

Looking at the specific survey results, when asked about the current biggest competitor, 62.5% of Korean companies answered "China," far exceeding the number of companies answering "United States" (22.5%) and "Japan" (9.5%). If the time frame is set to 2030, the percentage of companies answering "China" further increases to 68.5%. This actually means that most Korean companies believe that the existing global industrial structure will not undergo major changes, and the technological advantages of the United States and Japan will continue to slowly decline.

In 2025, with South Korea as the base of 100, the export competitiveness of the United States is 107.2, China is 102.2, and Japan is 93.5. By 2030, still using South Korea's situation at that time as the base of 100, the export competitiveness of the United States is 112.9, China is 112.3, and Japan's absolute value increases to 95.0, but the growth rate will be only 1.5%, which is very pessimistic.

In general, Korean companies point to manufacturing, exports, and supply chains as the main sources of pressure, reflecting their great concern about direct confrontation with China in similar tracks. The rising "perception of competition" indicates that not only in terms of production capacity and price, but also in structural expansion supported by technology and capital, Korean companies will increasingly lose advantages and confidence. Although the "high-end position" of the United States can be maintained for some time, the shrinkage of its system is inevitable. Japan's decline is the result of this shrinkage combined with long-term industrial structure, demographic factors, and other domestic issues.

In specific industries, according to Korean entrepreneurs, China has an absolute advantage in steel, general machinery, secondary batteries, displays, and automotive parts, and these advantages will continue to grow. These are sectors where scale economy and deep supply chains can form strong moats, and the combination of price, production capacity, and industrial policy creates an advantage loop.

At this point, although Koreans are considered to have "opened their eyes to the world," they may still underestimate China's potential and future. From an industrial foundation perspective, China's crude steel output has remained the highest in the world for 29 consecutive years. From an energy perspective, China is the only country in the world with annual electricity generation reaching a scale of 10 trillion kilowatt-hours.

Cheap energy will bring qualitative changes in production and life. During the Industrial Revolution, Britain had 77 times more total steam horsepower than France, which helped Britain become the "top dog" in both industry and military. In 1920, the U.S. total power generation was 56.6 billion kilowatt-hours, Germany 15 billion, Britain 8.54 billion, and France 5.8 billion, laying the groundwork for the subsequent course of war.

In the 2030s, China's controllable nuclear fusion will make substantial progress, and the Yalong River project will advance, further significantly reducing electricity prices. From increasing the yield of photophilic plants like dragon fruit to conducting high-speed wind tunnel tests for advanced fighters and wave-hugging warheads, all require large amounts of electricity. Looking back at a certain point in the future, the electric vehicles that have recently stirred up the global car industry will merely be the smallest shock China brings to the world.

From the perspective of Koreans, the dimensions where the United States leads mainly include brands, specialized talents, and core technologies, specifically reflected in the advantages of upstream R&D and standard setting, allowing them to maintain "high ground dividends" in profit distribution. Through the financial and rule systems, this path, although still has residual influence, will eventually be broken through and replaced, just a matter of time. In this process, with population structure changes and the restructuring of the world market, Japan's mature manufacturing clusters will continue to age, innovation conversion efficiency will decrease, and the domestic market will shrink, leading to a long-term, continuous decline in growth elasticity.

In this overall trend of East rising and West declining, South Korea has its own calculations and concerns. After the establishment of the Lee Jae-yong government, various uncertainties were eliminated, and South Korea achieved six consecutive months of export growth in the second half of 2025. It is expected that South Korea's exports will exceed $700 billion for the first time in 2025. Looking at the growth, the largest pillar has shifted from energy, steel, and shipbuilding, to semiconductors being the only one standing out. In the first 11 months of 2025, South Korea's semiconductor exports totaled $152.6 billion, setting a new record for the highest annual export volume. At the same time, the export volume of other categories except semiconductors reached $487.6 billion, a decrease of 1.5% compared to the previous year.

Specifically, among the 15 major export categories, besides semiconductors (19.8%), automobiles (2%), ships (28.6%), biomedicine (7%), and computers (0.4%) showing growth, the remaining 10 categories such as general machinery (-8.9%), petroleum products (-11.1%), petrochemicals (-11.7%), steel (-8.8%), and auto parts (-6.3%) all showed declines. With Moore's Law becoming increasingly difficult to "squeeze oil," China's flash memory, memory technology is becoming increasingly complete, and breakthroughs in core technologies such as processors are imminent.

Although currently, South Korean companies such as Samsung Semiconductor can still eat "friendship offshoring" political meals together with TSMC, the semiconductor advantage gained by South Korea due to choosing the right path in the previous era is now wobbling. This also indirectly explains why Koreans hope that the United States has enough capability to maintain the existing market structure and market advantages.

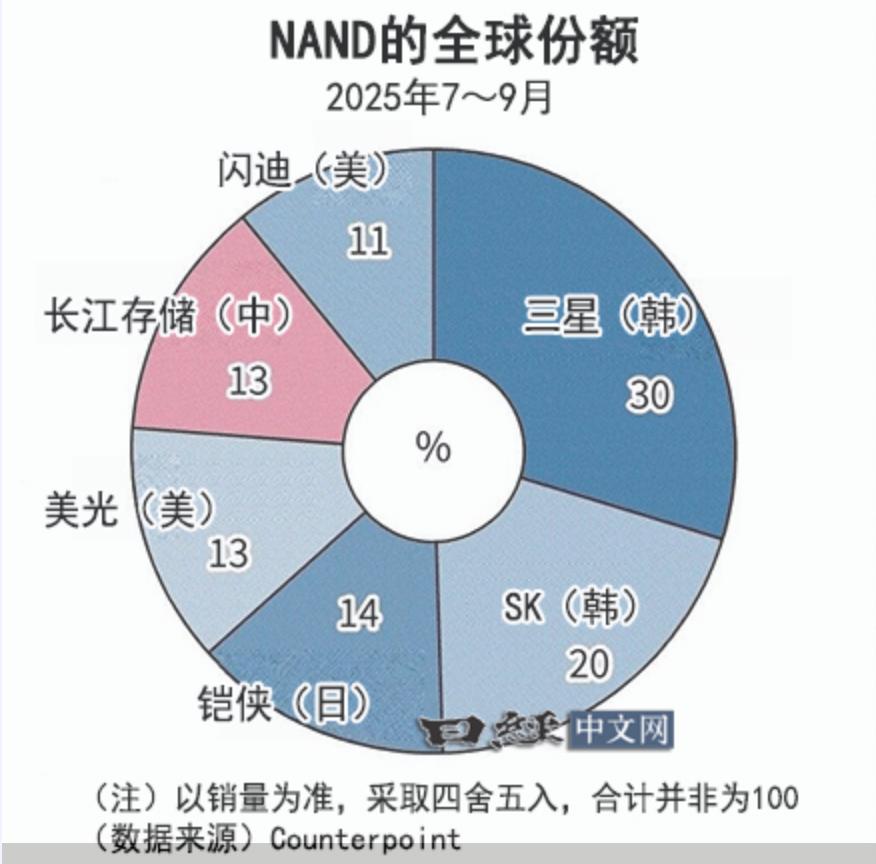

Japanese and South Korean industrial economic circles pay close attention to the development of Yangtze Memory and Changxin Memory, two Chinese companies with a market share of around 10%, but they are already viewed as the biggest competitors.

In addition to China's scale and system advantages entering the period of exertion, Japan and South Korea have another common concern about China's industrial economy, which is the internal competition of Chinese enterprises, which will eventually affect the two countries' enterprises.

On December 7, Park Man-su, senior researcher at the Korean Institute of Finance, released a report titled "The Situation of Chinese Enterprises' Low-price Exports and the Outlook for Structural Adjustment." The core conclusion of the report is that South Korea's manufacturing supply chain is closely connected with China, and with intense global market competition, South Korea finds it difficult to avoid the impact of China's overcapacity and low-price exports. As the front-line competitor in overlapping industrial structures, it should prepare earlier.

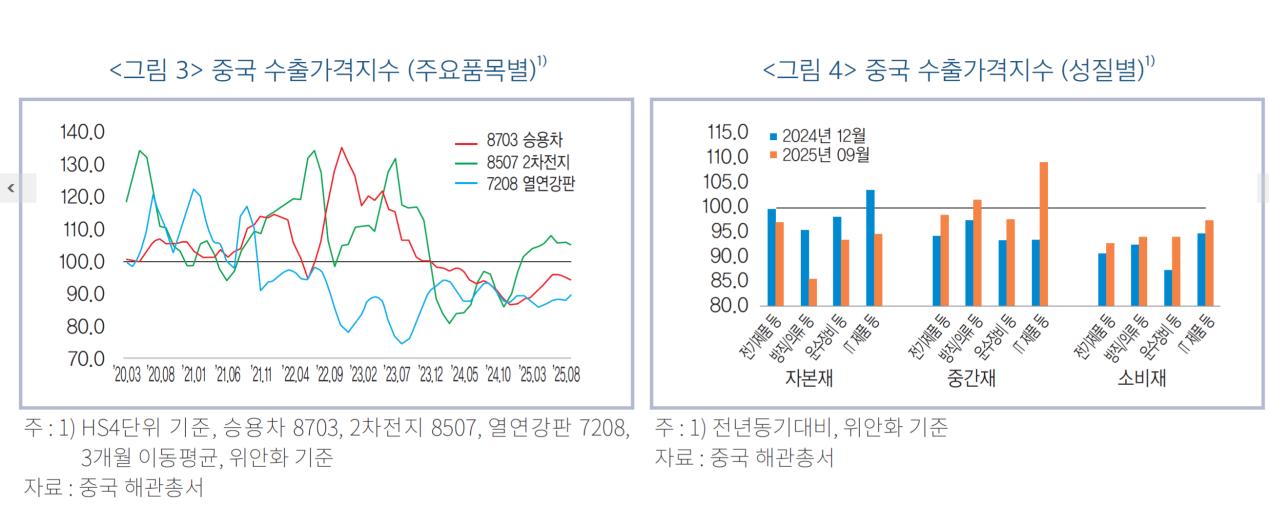

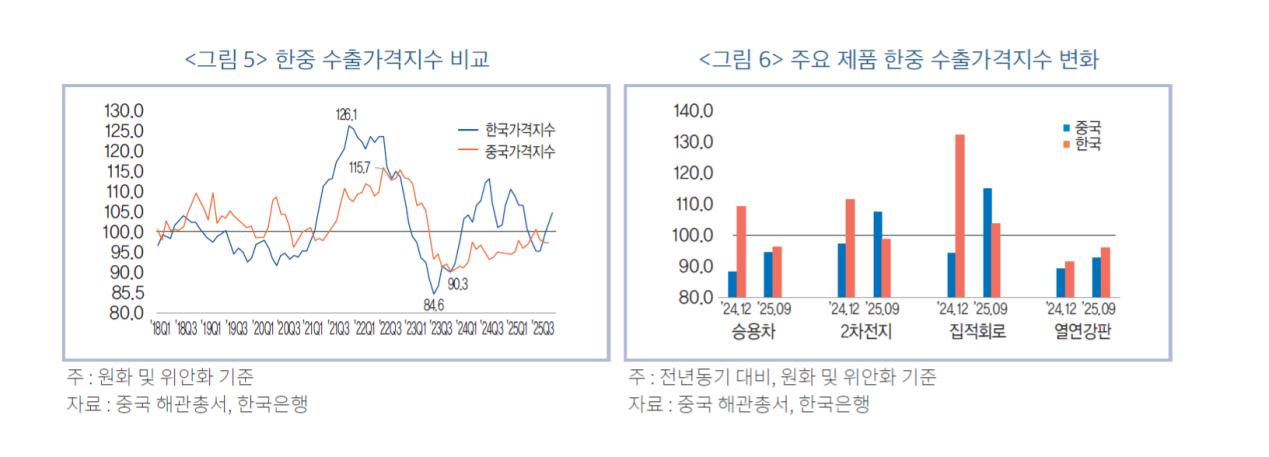

According to China Customs and other official data, the export price index of China, categorized by important items (passenger cars, secondary batteries, hot-rolled steel plates), and by nature (capital goods, intermediate goods, consumer goods), shows a clear trend of direct price cuts to stimulate consumption compared to capital goods and intermediate goods. However, the report does not reflect whether the consumer data includes subsidies.

In Park's view, the policies introduced by China, from invoice periods, purchase taxes, to new national standards, are all aimed at guiding electric vehicles from price competition to technology development competition, smoothly transitioning from internal competition to overseas expansion. During this process, China will become the standard setter for the next phase of electric vehicles, and the overflow of production capacity will inevitably impact the South Korean market.

The export price indices of South Korea and China are highly correlated, which is both a result of the global trend and indicates that South Korea is highly dependent on the Chinese market and supply chain. Regarding specific measures, the report suggests: first, in the consumer goods sector where China's export prices have dropped significantly, adopt differentiated competitive strategies in terms of quality and brand against Chinese products; second, in the capital goods and intermediate goods industries, maintaining stable transaction relationships with customers through mutual dependency within the supply chain is more effective than engaging in price wars. However, the report also acknowledges that the Chinese government's almost strict new electric vehicle standards may trigger a new round of technological breakthroughs by Chinese automotive companies.

The current South Korean government still hopes to extend the period of strategic ambiguity and delay the arrival of the moment of choosing between China and the United States. For South Korean companies, although they can temporarily avoid the extreme situation of closing one door and opening another, it also poses significant obstacles to better cooperation and healthy competition with Chinese companies.

Although the United States temporarily adjusted most of the tariffs on important South Korean industrial products back to 15%, bringing a阶段性 pause to the tariff war, similar situations will inevitably occur again in the future. The prospects of South Korea's industrial economy, like the strategy of the South Korean government, remain vague.

This article is exclusive to Observer Net. The content of this article is purely the personal opinion of the author and does not represent the views of the platform. Without authorization, it is prohibited to re-publish, otherwise legal responsibility will be pursued. Follow the WeChat account guanchacn of Observer Net to read interesting articles every day.

Original: toutiao.com/article/7581646722112225838/

Statement: This article represents the personal views of the author.