The competition between China and the United States has become a key element of the current international order. The Trump administration in the U.S. frequently took actions, colluding with its allies to suppress and contain China. On one hand, China actively responded and retaliated equally; on the other hand, it became more active on various international stages, effectively participating in, even leading major international issues. However, Western countries always maintain suspicion or even malicious criticism toward China's actions, encouraging other countries to "take sides."

Today, in the international public opinion arena, more voices are emerging regarding Sino-U.S. relations and the global order, such as Trump's so-called "big deal" and redefining "new spheres of influence," etc. How does China view these?

In this issue of "Pacific Polarity," the guest is Zhao Long, Deputy Director and Researcher (Professor) of the Institute of International Strategy and Security at the Shanghai Institute of International Studies, and a member of the Chinese Association of International Relations. His main research areas include global governance, great power relations, and oceanic and polar studies. In this dialogue, Zhao Long proposed that both China and the United States understand that confrontation is not an option. But China is also clear about the so-called "Trump big deal," some issues and principles cannot be traded, and these bottom lines must be upheld. Regarding the concept of "new spheres of influence," it does not align with China's long-term interests because it cuts off flexibility; at the same time, it contradicts China's thinking about the future global order, and China has the capability to counter it.

[Interview and translation by Li Zexi]

Li Zexi: September has been a very busy month for China. Besides the commemoration activities for the 80th anniversary of the victory in the War of Resistance against Japan mentioned earlier, there was also the SCO summit held in Tianjin at the beginning of September. Why does the SCO involve non-security fields, such as the global governance initiative proposed at the summit, and even the establishment of the SCO Development Bank? Will this cause it to lose its identity as a security organization? After all, China already has many initiatives and mechanisms related to global governance and regional development. You can also talk about your other views on this summit.

Zhao Long: This is a very good question. First of all, this summit was not an ordinary meeting. More than 20 heads of state attended, making it the largest SCO summit in history; moreover, it coincided with the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II, which had significant symbolic meaning.

I think the SCO is positioning itself as a balancing force against unilateralism. But if it only stays in the "empty talk" of security issues, it will not play a role. Because real security is built on the foundation of development. That is why this year's Tianjin summit saw specific measures proposed by leaders of various countries involving broader areas of cooperation.

On August 31, President Xi Jinping and his wife hosted a welcome banquet in Tianjin for international guests attending the 2025 SCO Summit. CCTV News

The key point is to look at the challenges faced by Central Asian countries and some new members: energy shortages, digital divide, and insufficient infrastructure for connectivity, which can lead to instability. This instability, in turn, can give rise to "three forces": extremism, terrorism, and transnational organized crime. The initial mission of the SCO was to address these non-traditional security threats.

On the other hand, regarding the SCO Development Bank, this idea has been around for nearly 15 years. The reason why countries finally reached consensus and started the construction of the Development Bank at this summit is that member states are pushing large-scale infrastructure projects, such as roads, railways, and connectivity projects. Many countries are entering green and digital transitions, while the existing multilateral financial system has a huge funding gap. The SCO Development Bank aims to fill this gap. It is not intended to compete with the AIIB, BRICS Development Bank, Asian Development Bank, or World Bank, but rather to serve as a complementary mechanism.

Certainly, your concern is reasonable. As the agenda expands, the SCO may face "loss of focus"; especially since it adheres to the principle of consensus, achieving agreement is difficult. However, from the results, the summit also established four new security cooperation centers, such as counter-terrorism, drug control, and combating organized crime, while proposing new platforms in areas such as the digital economy and artificial intelligence. Overall, I believe this is a more practical form of cooperation, emphasizing "deliverable results" rather than staying only at the level of principles or grand narratives.

So I would say that the SCO is undergoing an evolution. But one thing needs to be clarified: the SCO is not aiming to become an "Asian NATO" or some regional alliance. It remains a functional platform, focusing on the practical needs of regional countries. Overall, I believe this Tianjin summit is more significant than any previous SCO meeting.

Li Zexi: You just mentioned the infrastructure of connectivity. But isn't this exactly the focus of the "Belt and Road Initiative"? Why does the SCO also need to carry out connectivity construction?

Zhao Long: As I said earlier, the gap in connectivity infrastructure is very large, requiring massive investment. I believe that China alone cannot fill this gap. This is why the "Belt and Road Initiative" was initially designed as an open initiative, requiring participation and contributions from all parties to achieve synergistic effects. But the problem is that the "Belt and Road Initiative" does not have a specific mechanism to ensure funding requirements.

Whereas the SCO Development Bank is different. Of course, it is not yet clear how the bank's institutional construction will proceed, such as how shares will be distributed among countries, how voting rights will be determined, and how decision-making mechanisms will be established. But one thing is clear: this is not a symbolic political statement, nor is it merely a grand plan, but a concrete mechanism, like the New Development Bank of BRICS or the AIIB. This platform will certainly draw on the operational models of mature multilateral financial institutions. Therefore, I believe there is a difference between the two.

Li Zexi: Recently, we have seen Poland completely closing its border with Belarus for two weeks due to Russian drone incursions and the Russia-Belarus "Western-2025" military exercise. This has affected China, as it effectively cut off the main land-based "Belt and Road" corridor. China and other countries are exploring alternative solutions, especially the so-called "Middle Corridor." However, recent major news has come from Washington, where the U.S. announced it will promote a new route through Azerbaijan-Armenia-Turkey. Is China concerned about the U.S. interfering in this emerging trade chokepoint? More broadly, as geopolitical tensions continue to add new barriers to trade, how will China adjust its strategic thinking?

Zhao Long: This is a very timely question. The geopolitical landscape of the entire Eurasian continent is becoming more fragmented. Of course, China's development, its initiatives, and projects are inevitably affected by these geopolitical conflicts, even military conflicts.

First, let's talk about the "Middle Corridor." I just returned from Baku in Azerbaijan and had in-depth exchanges with my counterparts there. The Azerbaijani side is very proactive in encouraging China to participate in this grand project and hopes that China will increase investments and introduce Chinese technology.

The railway network connecting China and Europe via Central Asia and the Caucasus is called the "Middle Corridor" (Central Corridor). Nikkei Chinese Net

You're right, the competition is indeed intensifying. It seems that President Trump is indeed intent on intervening in the region's affairs to serve the purpose of "balancing" China.

But looking at the route itself, the "Middle Corridor" is theoretically very attractive: it bypasses some of the most intense conflict areas, such as the Ukraine-Russia conflict zone; meanwhile, the route is shorter and can connect many countries along the Caspian Sea, with potential to link the two major markets of China and Europe, and there are many rapidly developing economies along the way.

However, the reality is that the current infrastructure is far from mature, and the integration and maturity of land routes are nowhere near those of the existing Russia-Belarus corridor.

There are both great opportunities and many challenges here. The U.S. supports this route and tries to ease the conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia, making the situation more complicated. For China, the risks mainly fall into two aspects: first, economically, if the U.S.-led project really can divert trade, then China's corridors, and even the long-term plans of the "Belt and Road," will be affected. Second, geopolitically, this is not just about building roads and laying tracks, but about the long-term vision of connectivity. If Washington sees this region as a key battlefield for competition with China, implementing relevant plans will become more complex.

On August 8, US President Trump, Azerbaijani President Aliyev, and Armenian Prime Minister Pashinyan attended the signing ceremony of the final peace agreement between the two countries in the White House. French media

I think China will directly respond to this reality by diversifying cooperation. We do not see the "Middle Corridor" as a replacement for existing channels, but as an additional choice. Beijing will simultaneously increase investments and resource allocation on the "Middle Corridor" and other potential corridors. The space of the entire Eurasian continent is vast, and the demand is also significant, as it directly connects the two major markets of China and Europe. Therefore, I believe that diversification will be the core answer for China to cope with geopolitical risks and promote regional connectivity cooperation.

Li Zexi: There is a saying in China that the competition between China and the United States is detrimental to small countries caught in the middle, with the metaphor being "elephants fighting, grass suffering." But I don't entirely agree with this. For example, after the first term of Trump, when the Sino-US trade war was launched, many Southeast Asian countries actually received a lot of investment inflows. In the Pacific region, some island nations have also been playing both sides to gain maximum benefits. What do you think about this phenomenon? In your communication with regional colleagues, is this "victim theory" widespread, or do more people believe that Sino-US competition could bring opportunities?

Zhao Long: I would say that the Sino-US trade friction or the so-called "tariff war" affected regional countries, especially Southeast Asia, as the Trump administration not only targeted China but also many other countries.

In a sense, these countries have become one of the winners. Some countries have benefited from the transfer of industrial chains due to tariff factors, such as Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, etc., which have received an influx of manufacturing and investment. This is a positive aspect.

But undoubtedly, there are negative aspects as well, because no country can completely stay out of the game of great powers. These countries are not passive recipients, but rather, as you mentioned, they adopt "hedging" strategies, positioning themselves as neutral and pragmatic players. On one hand, they remain open to Chinese investments and infrastructure under the "Belt and Road" initiative; on the other hand, they continuously deepen their relationship with the United States to obtain advanced technology and market access.

Therefore, I think these countries do not simply regard Sino-US competition as a risk. For some of them, competition also means opportunity. By balancing both sides, they can seek more benefits in investment, trade, and even technology transfer.

In my communication with regional colleagues, I feel their strong pragmatism. They want diversification, avoid over-reliance on any one side, and maximize their room for maneuver. This is quite different from the "zero-sum competition" narrative often described by Western media.

The mindset of Southeast Asia is more "transactional": even if great power competition will continue for a long time, what they should do is use the competition to serve their own development. Balancing will continue, these countries will keep trying to gain maximum benefits between China and the United States, but they will increasingly insist on acting according to their own interests and ways. In other words, they do not want to be just pawns in the game of great powers, but want to become more proactive actors.

Li Zexi: When Trump was elected, there were some debates. Some people thought that China might be happy with his election, as his transactional style might facilitate major agreements, even "big deals," while weakening the U.S. alliance system; but others thought that China did not like the huge uncertainty brought by Trump, not only in the trade war, but also in other aspects, as China's political system tends to be more risk-averse. Now, eight months into Trump's presidency, from China's perspective, which side is more inclined?

Zhao Long: Eight years have passed, and I think Beijing has accumulated a lot of valuable experience in dealing with the Trump issue. Everyone is clear that his second term is completely different from his first term, and his attitude towards China has also changed. You said he is transactional, I agree. From an overall perspective, his foreign policy is indeed transactional, but on the surface, it still appears quite confrontational, such as the continuation of tariffs, and we have also seen the U.S. continuing to push for "decoupling" in high-tech fields, such as chips. At the same time, we have also seen the White House making selective concessions, such as recently relaxing export controls on certain categories of chips, and even being willing to negotiate on issues like TikTok.

Therefore, I think the signal that Trump sends to China is quite complex. From China's perspective, the U.S. does not seem to be fully prepared, or firmly continue the Biden-style approach to China - the gradual promotion of the so-called "decoupling" strategy. Instead, the U.S. seems to be deliberately maintaining negotiation space and being willing to compromise when necessary. This gives China considerable room for maneuver, allowing us to readjust our strategy towards the U.S.

I think both sides clearly know that confrontation is not an option. For Trump, of course, he wants to make "big deals" with every major power, including China. But China is also clear that some issues and principles cannot be traded, and these bottom lines must be upheld.

The differences in thinking and strategic considerations between the two countries bring both risks and opportunities. Dialogue with the U.S. itself can provide a certain degree of stability, which is important now. But on the other hand, Trump remains unpredictable. You can never confirm whether he really wants to reach and implement an agreement, and you can only guess based on his tweets or social media posts, which often contradict the official position of the U.S. Therefore, I think China remains highly cautious and focuses more on practical progress on specific issues rather than seeking a "big deal".

Future developments may become clearer, such as the leader's meeting in South Korea in October, and Trump's possible visit to China. These will help both sides better understand each other's intentions, giving China a more predictable judgment of Trump's true purpose. Of course, we also need to pay attention to the new U.S. National Defense Strategy that will be released by the new Trump administration. If it includes new narratives and positions on China, it will also send some positive signals for bilateral interactions.

Li Zexi: How closely is China watching the U.S.-Russia talks on Ukraine? Will China try to influence the outcome of the negotiations? I noticed that this is also a topic discussed at this year's Xiangshan Forum.

Zhao Long: First of all, China is certainly closely watching the U.S.-Russia talks, but not with the "high tension" tone commonly found in U.S. and European media. For example, China does not believe that the so-called U.S.-Russia "reconciliation" or "normalization of relations" has truly occurred after the Alaska Summit. China tends to think that it is more like "a lot of noise but little substance." Because from the Chinese perspective, there are structural hard constraints in the U.S.-Russia relationship. Trump may say today that he wants to improve relations with Russia, but the next day he may threaten to impose sanctions or speak disrespectfully about Putin, which reflects the unpredictability of Trump's policies.

Moreover, if he makes any substantial concessions on major issues such as Ukraine, NATO, or sanctions, there will be a strong backlash within the U.S. This is particularly critical for Trump, as from the end of this year, the U.S. will enter the midterm election cycle, so his policies are likely to focus more on domestic agendas rather than foreign policy.

At 11:30 local time on August 15, the U.S.-Russia summit was held in Alaska. White House

Additionally, there is a severe trust deficit between the U.S. and Russia. I just came back from Moscow and had several rounds of dialogues with Russian strategic experts and former officials. They have a considerable amount of skepticism about the outcomes of the Alaska Summit. There is a fundamental lack of trust between the establishment of both countries.

Therefore, I would not call it "rapprochement" or "reconciliation," but rather "dialogue is ongoing." For China, this is a good thing. But to say that the U.S. and Russia can engage in deep cooperation, it will probably take a long time.

For China, the fact that the U.S. and Russia are trying to rebuild some communication and dialogue channels is not a bad news. Because this can significantly reduce the risk of miscalculation and reduce the pressure on China to take sides. On the other hand, if the U.S. and Russia can find some specific solutions to the Ukraine war, such as a temporary ceasefire or initiating a comprehensive peace talks, China will benefit. Because this will greatly reduce the threat of "secondary sanctions" against Chinese companies.

Li Zexi: You recently wrote an article in The Diplomant, refuting the idea that "China may support dividing the world into spheres of influence." But as you mentioned in your article, Russia is very willing to accept this framework, and recent reports show that the U.S. is also seriously pushing in this direction, especially the draft of the new U.S. National Defense Strategy, which may shift the focus to protecting the homeland and the Western Hemisphere, rather than focusing on China as before, which aligns with some U.S. domestic ideas about spheres of influence. If both Russia and the U.S. support the logic of spheres of influence, can China really, and is it willing, to be the only major power opposing their ideas? On the other hand, perhaps some people might think that in the old globalized, interconnected international order—regardless of how hard China tries—it may be difficult to restore, and this "sphere of influence" framework may be more stable, and China usually supports arrangements that are conducive to stability.

Zhao Long: This is a very good question, and I think it directly involves the core of China's thinking about the future global order. As you mentioned, I put forward in my article that the trend of redefining "spheres of influence" is rising in Moscow and Washington. China's stance is very critical in this context.

First, what is a "sphere of influence"? For Russia, it almost means returning to the logic of 19th-century geopolitics: defining hard borders, establishing buffer zones, and even interfering in neighboring countries' choices. For the U.S., the upcoming new National Defense Strategy may focus more on homeland defense and dominance in the Western Hemisphere. This looks more like it is shifting from the role of a global hegemon after the Cold War to a regional hegemon, which could evolve into the logic of spheres of influence.

But can China alone oppose this trend? I think the answer is "yes." But the reason is not just that China "is committed to maintaining globalization," which is just one factor. More importantly, China's rise itself is built on an interconnected system, open markets, global supply chains, and capital and technology flows. "New spheres of influence" do not align with China's long-term interests, as it cuts off flexibility. Imagine if Southeast Asia or Africa suddenly falls into the sphere of influence of a major power, China's "Belt and Road" and other collaborations would be severely constrained. Moreover, stability is also an issue.

Furthermore, "spheres of influence" reminds people of the Yalta system, and China was one of the biggest victims of it. This obviously does not align with China's proposed multipolar world and the "community with a shared future for mankind" concepts. Therefore, China will not accept this logic. Not because it wants to "stick to the past," but because China's interests are deeply dependent on an open global system. China would rather promote a more sustainable multipolar world rather than be locked into this camp-based, sphere-of-influence framework.

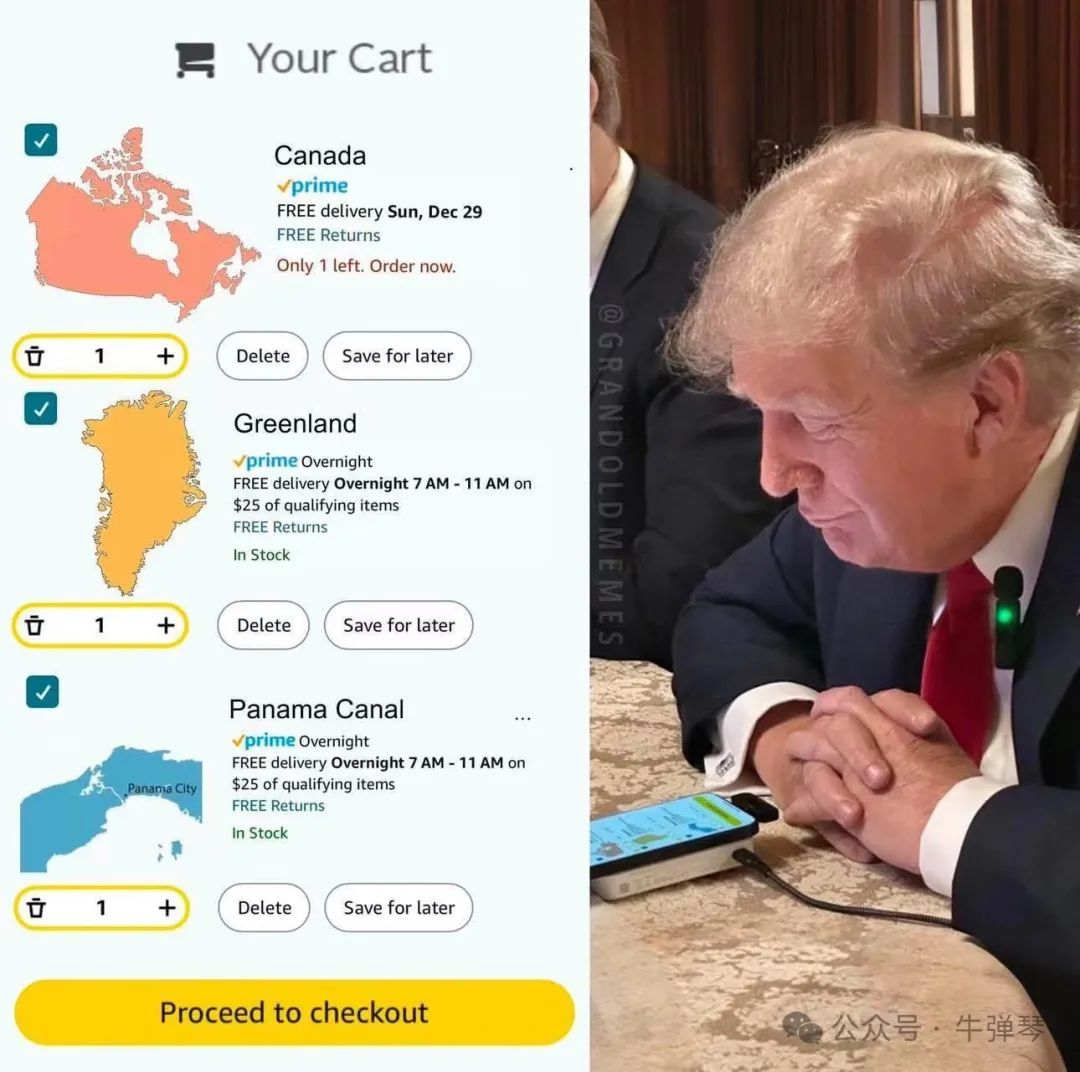

Trump previously posted an image of an online shopping cart on a social media platform, with three items being Canada, Greenland, and the Panama Canal

Li Zexi: The outside world indeed has doubts about whether China genuinely commits to an "equal, democratic, multipolar international order." According to historical logic, great power politics almost always follows a fixed pattern, so many naturally feel that there is no reason to believe China can break out of this geopolitical model. Can you understand the external doubts about China's position?

Zhao Long: This is a reasonable question. I think it touches on the credibility of China's multipolar discourse: on one hand, China's statements, and on the other hand, the behaviors perceived by regional countries. Indeed, historical experiences themselves also foster suspicion. Everyone knows that superpowers, major powers have acted in the past: Britain, the U.S., etc., they delineate spheres of influence and dictate what neighboring countries should do. So when China says it is a "different country" and will have "different practices," many naturally ask: why would this time be different? I fully understand this concern.

But I want to emphasize a few points. If you observe China's entire political and governance system, not just the ideological part of "Socialism with Chinese Characteristics," you will find that it is significantly different from other major powers. China was one of the biggest victims of great power博弈 and power politics in the last century. I think China has no intention of repeating this. At the same time, China is very pragmatic; it clearly knows that it cannot impose order everywhere in the world, nor can it build an order that only serves China's single-sided interests.

Moreover, I believe that China has no interest in creating U.S.-style military alliances. China is more inclined to prevent being surrounded and to maximize its strategic room for maneuver, while accommodating the general demands of "Global South" countries - which mainly care about development agendas, not security agendas.

Therefore, I understand why some ASEAN countries and European countries are skeptical, but I would suggest that they observe China's actual actions and commitments. History will prove that China is indeed a different "rising power." If you explain China's role and intentions using old narratives and old logics, it is neither accurate nor possible to arrive at the correct conclusion.

Overall, if you look at the "Four Initiatives" proposed by China, you will find that these initiatives are completely aligned with China's vision of a multipolar world. As long as you pay attention to China's subsequent implementation steps, you will find that China's differences are not only reflected in rhetoric and narratives, but also in substantive content.

Li Zexi: Finally, I would like to point out that at least in Australia, many people have doubts about the moral arguments China puts forward. For example, you emphasized that China was a victim of great power博弈 in the past, but can this argument stand up in the long run? Because China itself has now become a major power. More specifically, you mentioned that China advocates a multipolar world order, but will China support a multipolar Asia? Because a multipolar world order may still allow for some form of spheres of influence, and if China supports a multipolar Asia, this may more clearly indicate that China will not follow the traditional power politics and hegemonic path mentioned earlier. What is China's vision for Asia?

Zhao Long: You're right. Regarding the concept of a multipolar world and multipolarity, there are different schools of thought. We just talked about the logic of spheres of influence, where one school's core is that major powers divide the world into different regions, which can be called multipolarity. Another school is a multipolar world based on the principle of coexistence, where different poles may confront each other, which is another version of multipolarity.

I think China advocates a multipolar world based on complementarity. Especially in Asia, the recent Central Asia Conference clearly stated that China will view neighboring countries and regions as a key space for its cooperation and development, which is crucial for China's security. In other words, on one hand, China still pays attention to great power relations, and on the other hand, China will increase its investment and resource allocation in regional affairs. In this context, China does not want to see more poles forming in Asia with an adversarial posture; obviously, the alliance trends in Asia do not align with China's interests.

The concept China advocates is that Asian countries should manage regional affairs and agendas themselves and try to form some Asian values or an Asian regional order vision, rather than continuing the old power politics and traditional narratives. China can play a greater role in this by providing more public goods, solving the practical problems and needs of regional countries, and expanding the overall "cake."

Of course, if the outside world lacks understanding of Beijing's strategic intentions and has inaccurate perceptions of China, then implementing these initiatives and plans will be impossible to succeed.

Therefore, from my personal point of view, the future regional order or regional interaction structure will become one of the priority items in China's foreign policy, economic policy, etc. I think the main factors that may affect this long-term process are external factors, such as the intervention of external countries like the U.S. Therefore, my answer is: for regional countries, we should formulate our own vision and values; for other major powers, China will certainly strive to manage differences with major powers in Asian regional affairs.

Li Zexi: Today, I would like to thank Dr. Zhao Long for the interview, and I look forward to more discussions in the future.

Zhao Long: Thank you for inviting me, I am glad to participate in this dialogue.

This article is an exclusive article by Observer, the content is purely the author's personal opinion and does not represent the platform's views. Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited, otherwise legal responsibility will be pursued. Follow the Observer WeChat guanchacn to read interesting articles daily.

Original: https://www.toutiao.com/article/7560951855442952754/

Statement: The article represents the personal views of the author. Please express your attitude by clicking on the [top/foot] button below.