【Text by Guan察者网 Columnist Mao Keji】

Castes are a profound and somewhat enigmatic existence in India. If you randomly ask an Indian on the street, "How many castes are there in India?" one thousand people might give one thousand different numbers. Now, this question may finally receive a definite answer.

In June of this year, the Indian Ministry of Home Affairs officially announced that it will complete a national census by March 2027, and for the first time in history, it will include information about "all castes" in the questionnaire. This decision means that after the last successful caste census during the British colonial era in 1931, India will systematically clarify the true situation of the caste population across the country after nearly a century.

This decision has already sparked widespread discussion both within and outside of India, as the caste system influences every aspect of Indian society and touches upon deeper cultural and historical issues. The new nationwide caste census not only affects the future direction of caste politics and social equity but will also have a far-reaching and comprehensive impact on India's major policies and economic prospects.

One, Caste System and Modern Dilemmas

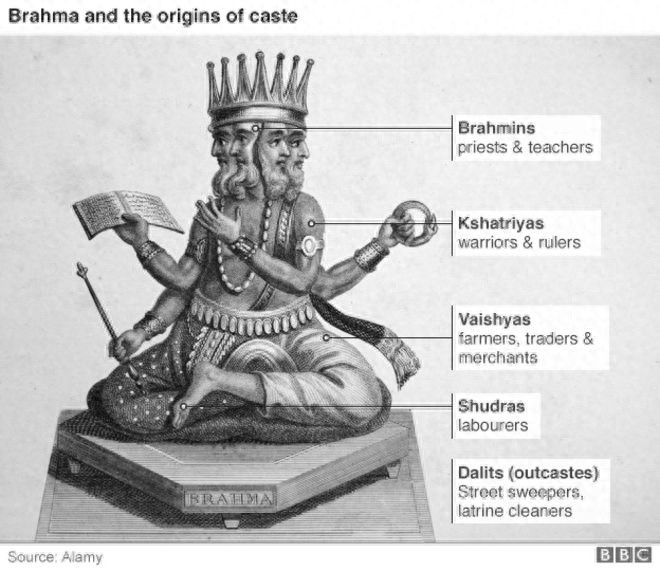

The caste system originated from the Varna system of ancient Hinduism. In theoretical texts, people were divided into four main "Varnas": Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras, plus the "untouchable" Dalit community; however, in reality, people are more often divided into thousands of smaller "Jatis" based on customs, occupation, and bloodline.

In reality, there may be thousands of castes in India

Although India abolished caste discrimination after independence in 1947 through its constitution and implemented affirmative action policies such as quotas to correct "historical injustices," forming legally favored lower caste groups including Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST), and Other Backward Classes (OBC), under the background of India not having experienced a violent revolution or thorough reform, the caste system, as a cornerstone of social culture, still remains deeply rooted.

According to tradition, India conducts a national census every ten years as a basis for constituency division and resource allocation, but the planned 2021 census was postponed due to the pandemic and has not been launched yet.

Since India's independence, whether it was the BJP or the INC in power, all previous governments avoided a national caste census, fearing that the complexity of caste itself and the controversies surrounding caste issues could further intensify conflicts, split society, and even undermine the foundation of modern India. For example, the Indian government has long been reluctant to publish the exact proportion of OBCs, with the policy intent being to avoid expanding the quota system.

From this perspective, the Modi government's recent decision to break the convention and introduce statistics on "all castes" is a major political decision.

According to the Indian Ministry of Home Affairs, conducting a caste census aims to accurately grasp the structure and distribution of various social groups, thereby providing data support for future welfare policies, educational resources, fiscal transfers, employment plans, etc. This "data-driven governance" logic is theoretically reasonable, but its real motives and potential consequences go beyond this—there are at least three pressures behind it.

Two, Practical Motives Behind the Census

Firstly, the Modi government's push for the caste census is a direct response to recent changes in internal politics.

In the 2024 election, although the BJP won re-election, its seats dropped significantly, and it failed to achieve a majority, which was largely due to poor performance in regions with large OBC populations such as Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, especially among traditional middle and lower castes, where support rates declined. In contrast, the opposition alliance led by the INC, "India National Development Inclusive Alliance" (INDIA), clearly proposed the slogan "the number of people determines the rights," gaining support from a large number of middle and lower castes.

This size-based equity demand severely challenges the BJP's proclaimed "development first" narrative, directly pushing the BJP to take the demands of middle and lower castes regarding representation and resource allocation more seriously. The Modi government is preparing to integrate caste data with the identity recognition system (Aadhaar) and social welfare cards, forming a cross-departmental stratified governance database. This data governance approach transforms the caste census from a political taboo into a variable for precise resource allocation and fiscal planning.

Modi speaking to supporters at the BJP headquarters after winning. Photo from The New York Times

Secondly, even if the Modi government takes no action, the states have already started acting on their own.

For example, Bihar, where the caste issue has significant influence, completed a caste survey within the state in 2023. The data showed that the combined population of OBCs and the more disadvantaged "Extremely Backward Classes" (EBC) reached 63%, far exceeding the national quota of 27%. Following this, Maharashtra, Odisha, and Tamil Nadu also proposed to conduct local caste censuses and sought to expand corresponding quotas.

In this situation, if the BJP and the central government do not conduct a unified caste census, they may lose policy leadership due to the lack of up-to-date data, leading to the fragmentation of caste politics by local forces. Facing the offensive of the opposition party at the local level, the BJP chose to "take the initiative," using the caste census to strengthen the image of the Modi government as "pro-people." The census data can be used to expand welfare programs targeting middle and lower castes, including additional quotas, thus consolidating support.

Finally, the actions of the Modi government are also driven and accelerated by institutional timelines.

According to the Indian Constitution, the allocation of parliamentary seats is frozen until 2026, after which it must be re-divided based on the latest census data. If this schedule is followed, the number of seats in each state, the power structure of parties, and the basis for fiscal transfer payments over the next decade will be affected. In other words, whether the population data includes "caste information" will largely determine the resource allocation logic over the next decade.

Therefore, the BJP hopes to control the data initiative as much as possible, avoiding radical reforms that would break the 50% quota ceiling, and linking caste data with socio-economic development indicators to weaken the opposition party's purely scale-based caste mobilization.

Three, The Position and Calculations of the Hindu Right

Notably, the BJP's sudden policy shift has also received support from its ideological mother organization, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS).

The RSS, as a Hindu nationalist organization, has long viewed caste as a divisive factor within Hinduism, emphasizing "Hindutva" (Hindu characteristics) to transcend narrow identities such as caste, language, and class. Its stance against caste census reflects the RSS's long-term concerns: caste data may strengthen identity, weakening its efforts to build a unified Hindu voter bloc.

However, in recent years, the RSS has changed its position, beginning to support the caste census, even seeing it as an opportunity for promoting "social harmony."

At a national meeting of cadres in 2024, RSS leader Bhagwat openly stated, "To achieve genuine social harmony (Samajik Samarasata), we must recognize the realities of inequality and implement compensatory policies accordingly." Such statements can be seen as a form of ideological "soft landing," marking that the RSS no longer views caste discussions as a divisive issue, but rather as a necessary cost for achieving an inclusive national identity.

The RSS even hopes to promote "caste integration" through the census, such as encouraging inter-caste marriages and educational reforms, serving its long-term goal of building a unified national identity and a strong Hindu state.

Photo of the RSS in India

Four, Risks and Challenges of the Census

However, the Modi government's push for a nationwide caste census may face various risks and challenges.

Firstly, once the national-level caste data is released, it will inevitably trigger dissatisfaction and hostility among all levels of society.

Previously, due to the lack of authoritative national caste data, different caste groups remained in a relatively vague state when striving for their own rights. Once the data is published, caste groups whose actual population is less than expected may strongly oppose it, while larger but still backward groups will urgently demand the government to increase quotas and welfare, leading to "high caste deprivation feelings" or "low caste quota expansion anxiety," which may trigger legal lawsuits, street politics, mass protests, or even bloodshed.

For example, if the OBC population is indeed over 50%, but the current central quota system remains at 27%, it will inevitably trigger a wave of "matching scale with welfare" in the political sphere. This may force the Modi government to amend the constitutional limit of 50% quotas or make alternative arrangements.

Secondly, ensuring the quality and authority of the data itself is a challenge.

During the 2011 Social Economic and Caste Census (SECC), a large number of self-created caste names and repeated information led to 4.6 million records that could not be corrected, and the official results were never officially released. Although the current census has clearly adopted AI deduplication and digital tools, whether it can successfully avoid similar quality issues remains unknown.

For example, regional differences in caste names, a wide variety of self-created names, and problems with the quality of self-reported occupational data are common. If the algorithm and manual correction capabilities are insufficient, it will severely damage the credibility of the Modi government and make subsequent policy implementation extremely difficult.

Additionally, this census data may also impact India's economic operations.

Under the pressure of votes, public caste data creates conditions for local governments at all levels to set "soft quotas" for the private sector. In areas such as higher education, listed companies, civil service recruitment, and government procurement, there may be more "social representation review" clauses, challenging India's current enterprise recruitment and human resource model dominated by "market efficiency."

For example, the INC has already publicly proposed that private enterprises implement caste quotas, which will increase corporate compliance and human resource costs, further increasing the uncertainty of the market environment. In the context of India's industrialization and modernization being at a critical stage, such policies' impact on economic operations cannot be ignored.

Source of the photo: Indian media

Five, The Double-Edged Sword of Data-Driven Governance

Despite the considerable risks, the Modi government has made its decision, and in the coming period, it will rapidly push forward the collection, verification, and release of related data, while political battles at the state level will revolve around caste data. After 2027, the data obtained from the census will provide a basis for redrawing Indian parliamentary seats, redistributing central-local financial resources, adjusting quota policies, etc., and India's political map and public governance model may undergo significant changes.

From a longer-term perspective, if the Modi government can truly achieve "data-driven precise governance," using caste data to precisely support the grassroots, strengthen skills education, and employment opportunities, it may alleviate caste tensions and gradually lead Indian society toward a more equitable and modern development path. However, there is another possibility: deepening social divisions, increasing fragmentation, endangering the democratic foundation and economic operation of India.

Historically pushing for a national caste census tests not only the governing capacity of the Modi government, but also the wisdom and determination of Indian society to deal with sensitive issues. It is not just a statistical action, but a deep social dialogue about "who belongs to the nation, who enjoys rights."

For India, the caste census may be an opportunity, or it may be an unprecedented historical challenge.

This article is an exclusive article by Guan察者网. The content of the article is solely the personal opinion of the author and does not represent the views of the platform. Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited, otherwise legal liability will be pursued. Follow Guan察者网 WeChat, guanchacn, to read interesting articles daily.

Original: https://www.toutiao.com/article/7532299675567915555/

Statement: This article represents the personal opinions of the author. Please express your attitude by clicking on the [Top/Down] buttons below.