After 2008, the neoliberal ideology has undergone a continuous global disillusionment process. The soft power of the West, based on neoliberal ideology, has also been shrinking continuously. The era when telling stories could make the opponent self-destruct is over. Therefore, in order to realize and strengthen its international power, the United States increasingly relies on asymmetric interdependence formed in the international division of labor, specifically through sanctions and economic warfare.

In sanctions and economic warfare, technological sanctions and cyber sanctions have played an increasingly important role in recent years, becoming the most important part of the Sino-US rivalry. In the seventh chapter, third section of his new book "Sanctions and Economic Warfare", Professor Zhai Dongsheng from the School of International Relations at Renmin University has given a detailed discussion and review of the US's technological and cyber sanctions against the world in recent years. He summarized the characteristics and shortcomings of the US's policies in this area, as well as the reactions of various countries to changes in US policies.

【Author: Zhai Dongsheng】

Technological Sanctions and Technological Competition

During the globalization process after the end of the Cold War, technological globalization has played a key role in improving the quality of human life. The driving force behind this phenomenon lies in the rapid changes and cross-border flow of technology, enabling all countries, regardless of their level of development, to benefit from technological globalization. The flow of technology has become an important link connecting countries and people in the era of globalization, intertwined with the cross-border flows of goods, services, personnel, capital, and knowledge.

The core characteristics of technological globalization lie in the global allocation of R&D resources, cost sharing, global management of activities, and the sharing of results. Multinational corporations have led the rise of the "Global Innovation Networks" (GINS), which allocate R&D, production, and sales stages based on regional comparative advantages. This not only promotes technological exchange and cooperation between countries but also deepens mutual dependence. However, it also provides opportunities for countries that control key nodes of the global technology map to use this mutual dependence as a weapon, thereby promoting the reverse globalization of technology.

In recent years, China's reliance on key technologies from the West has allowed the latter to see the possibility of hindering China's development through technological decoupling. In this context, technological sanctions, together with trade sanctions and financial sanctions, have become the "three pillars" of economic sanctions in the 21st century.

China's growing strength in manufacturing is seen as a threat to the long-standing technological leadership of the United States. A series of events, including the sanctioning of ZTE for selling U.S. technology to Iran, the U.S. allegations of "intellectual property theft" and forced technology transfer by China, and the U.S. concerns about Huawei's position in 5G technology, ultimately led to the Sino-U.S. technological conflict. The U.S. began taking actions to prevent China from acquiring its technology, while China launched a plan to "de-Americanize" its supply chain and value chain. The current U.S. technological sanctions against China have four characteristics.

Firstly, the U.S. stigmatization of China's technology is the prelude to the Sino-U.S. technological war. The U.S. Congress claimed that "the Chinese government participates in and encourages behaviors that actively destroy the free and open international market, such as intellectual property theft, forced technology transfer, and financial subsidies, with the aim of achieving its predetermined goal of becoming a superpower in manufacturing and technology."

In 2014, the Obama administration charged five so-called "Chinese military hackers" with economic espionage, accusing them of hacking into computer systems of major U.S. steel companies and other commercial companies. In 2015, the Obama administration again accused the Chinese government of "stealing U.S. technology and commercial secrets via the internet," and threatened to freeze the financial and assets of "individuals and entities engaged in destructive attacks or commercial espionage" and prohibit commercial transactions with them. Ultimately, China and the United States signed a cybersecurity agreement in September 2015, pledging not to engage in or intentionally support cyber theft of intellectual property for commercial purposes, including commercial secrets or other confidential business information. This dispute temporarily came to an end.

However, after Trump took office, the stigmatization and suppression of China's technology intensified. In August 2020, Trump signed an executive order prohibiting anyone from conducting transactions related to WeChat and TikTok with Tencent and ByteDance. The U.S. claimed that WeChat and TikTok collected large amounts of personal and private information of Americans, serving China's "false publicity campaigns."

Two weeks before Biden took office, Trump imposed sanctions on eight Chinese apps, including WeChat Pay and Alipay, through an executive order, accusing them of allowing the Chinese government to track the locations of U.S. federal employees and contractors and establish personal information files, "infringing" on the privacy of American citizens.

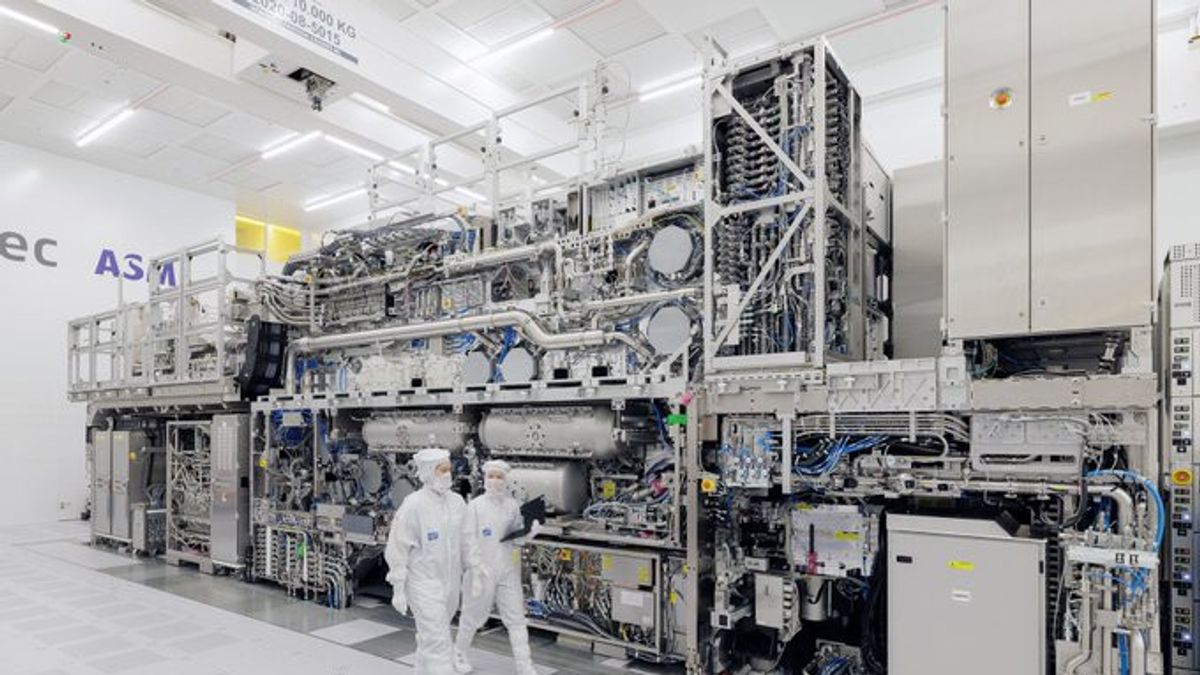

Secondly, the U.S. technological suppression focuses on Chinese high-tech enterprises and dual-use technologies. Chips, semiconductors, and integrated circuits are the core of modern technology, crucial for industries such as smartphones, televisions, digital cameras, LED bulbs, ATMs, medical equipment, and automobiles.

At the same time, chip technology is considered a key to unlocking future technologies, making the balance of global power potentially dependent on the ultra-thin and precision semiconductor chips being developed today. Targeting China's shortcomings in relevant industries, the U.S. has implemented a series of sanctions measures. In September 2020, the U.S. Department of Commerce announced export restrictions on China's largest chip manufacturer, SMIC. In October 2022, the U.S. Department of Commerce further implemented a package of sanctions against China, focusing on China's ability to localize the chip and semiconductor industry.

The U.S. continues to tighten export standards for Chinese chip machines

These sanctions include prohibiting U.S. companies from delivering certain advanced chip equipment to Chinese customers without a license, as well as restricting the transportation of U.S.-made electronic components or items that can be used to produce chip manufacturing tools and equipment in China.

Additionally, the U.S. has tightened the so-called "Foreign Direct Product Rule" (FDPR) to limit China's ability to obtain or manufacture advanced chips for supercomputers and artificial intelligence. It prohibits any U.S. or non-U.S. company from providing hardware or software containing U.S. technology to targeted Chinese entities in its supply chain. This sanction measure applies to global chip manufacturers, including U.S. companies such as NVIDIA, AMD, and Lam Research, as well as Dutch semiconductor equipment manufacturer ASML and Chinese Taiwan foundry TSMC.

In East Asia, the U.S. has formed the "Chip 4" alliance with Japan, South Korea, and China's Taiwan region. On the surface, it is a forum for discussing supply chain security and resilience, technological and productivity development, R&D and subsidies, but in reality, it is a small group coordinating policy positions on export controls and investment reviews of advanced semiconductor technologies to China.

Besides demonstrating "industrial hegemony" in chips and semiconductors, U.S. technological sanctions against China also involve aircraft engines and the aviation market. In February 2021, under U.S. support, Ukraine announced sanctions against Chinese companies such as Tianjiao Aviation attempting to acquire Ukrainian aviation engine manufacturer Motor Sich, including asset freezes and trade restrictions.

Even if Ukrainian companies are like this, U.S. companies are even more at the center of the storm, with the "Sword of Damocles" of banning CFM International, a subsidiary of General Electric, from exporting aircraft engines to China always looming. At the same time, the U.S. believes that the boundaries between China's civilian and military departments are becoming blurred, so it must target China's dual-use technologies in key areas and entities owned, controlled, or affiliated with the Chinese government, military, or defense industry.

In October 2018, the U.S. Department of Energy implemented restrictions on exports to China to prevent "illegal use of U.S. civilian nuclear technology for military purposes." In August 2019, China Nuclear Power Group and its three subsidiaries were listed on the U.S. Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) Entity List, due to being accused of "participating in or facilitating efforts to obtain advanced U.S. nuclear technology and materials for China's military use." In June 2020, the U.S. Department of Defense added Huawei, Hikvision, China Railway Construction Corporation, China Telecom, China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation, and Panda Electronics to its list of 20 companies it claims are owned or controlled by the Chinese military. In November 2020, Trump signed Executive Order 13959, prohibiting all U.S. investors from purchasing or investing in securities of companies designated by the U.S. government as "Communist Chinese Military Companies." In August 2022, BIS added seven Chinese aerospace and related technology entities to the Entity List, strictly limiting their access to goods, software, and technologies controlled by the U.S. Export Administration Regulations. As expected, the reason was also "China's military-civil fusion (Military-Civil Fusion) plan forces BIS to be vigilant to protect U.S. sensitive technology."

In May 2021, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia issued a final judgment, lifting the designation of Xiaomi Company as a "Chinese military company" by the U.S. Department of Defense

Thirdly, the U.S. uses national security as a pretext to legally justify sanctions and technological warfare against China. In August 2018, BIS decided to add 44 Chinese entities to the Entity List for sanctions, citing that they posed a "significant risk to U.S. national security or foreign policy interests." In May 2020, BIS further added 24 Chinese tech companies and institutions to the list, citing that these entities posed a "significant risk of using purchased items for China's military end use." In the same year, in August, 24 Chinese state-owned enterprises, including China Communications Construction Co., Ltd., were added to the Entity List, citing their role in "artificial island construction and militarization in parts of the South China Sea."

At the same time, the U.S. Department of State announced sanctions against individuals and their immediate family members who "are responsible for or involved in large-scale reclamation, construction, or militarization activities in the disputed areas of the South China Sea."

In April 2021, Tianjin Feiteng Information Technology, Shanghai High-Performance Integrated Circuit Design Center, Shenwei Microelectronics, as well as the National Supercomputing Jinan Center, Shenzhen Center, Wuxi Center, and Zhengzhou Center were added to the sanctions list by BIS, citing that the U.S. believes China is using U.S. supercomputing technology for military modernization, developing new nuclear weapons and hypersonic weapons, posing a "real threat" to U.S. national security. In June 2022, the U.S. Department of Commerce suspended the export privileges of three companies in Wilmington, North Carolina (Quicksilver Manufacturing Inc., Rapid Cut LLC, U.S. Prototype Inc.), citing that they were believed to have sent unauthorized technical drawings and blueprints of 3D printed satellites, rockets, and defense-related prototypes to China. Assistant Secretary of Commerce Matthew S. Axelrod stated, "Outsourcing 3D printing of space and defense prototypes to China would harm U.S. national security."

Additionally, the U.S. has taken measures to restrict the issuance of visas to Chinese students and researchers in science and engineering, sacrificing considerable revenue from educational services. On May 29, 2020, the White House government website published an announcement, stating that starting from June 1, 2020, certain Chinese students and researchers would be prohibited from entering the U.S. on non-immigrant status. According to the announcement, Chinese citizens holding F or J visas with graduate degrees related to China's military-civil fusion strategy would be banned from entering, except for specific exceptions.

Fourthly, in the evolution of U.S. technological policies toward China, technological sanctions are synchronized with the advancement of domestic industrial policies. Whether under the Trump administration or the Biden administration, attracting manufacturing and investment back, creating local jobs, and maintaining the U.S. leading position in the global technology field and its technological advantage over China have been the main goals. As a country that emphasizes "free competition" and practices neoliberal policies both domestically and internationally, the U.S. has traditionally been cautious in formulating industrial policies characterized by government support and investment in specific economic sectors.

However, in recent years, the U.S. has re-evaluated the role of differentiated industrial support policies in injecting economic vitality, stimulating technological innovation potential, and responding to great power strategic competition through a series of technological research and industrial policy-related legislation. In the Sino-U.S. technological competition, the U.S. leverages both sanction laws and industrial policies, adding external confrontation and internal enhancement in the Sino-U.S. technological competition, aiming to curb China's technological development while enhancing its own technological strength.

In June 2021, the U.S. Senate passed the United States Innovation and Competition Act (USICA); in February 2022, the House of Representatives passed a similar bill called the America Competes Act. USICA integrates provisions from the CHIPS and O-RAN 5G Emergency Appropriations, the Endless Frontier Act, the Strategic Competition Act, the Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee Provisions, and the Meeting the China Challenge Act, authorizing approximately $250 billion in funding.

This has been dubbed by media and think tank scholars as "the most extensive industrial policy legislation in U.S. history" and "the most comprehensive action taken by the U.S. Congress against China to date." Part of the content of USICA includes: (1) allocating $52.7 billion for domestic semiconductor manufacturing/research and development, and $1.5 billion for advanced communications research; (2) establishing a Directorate for Technology and Innovation (DTI) within the National Science Foundation, focusing on ten "key technological fields" that are regularly updated; (3) recommending that Congress provide $17 billion to the Department of Energy and $17.5 billion to the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) over five years to support their research and development programs; (4) recommending $9.4 billion to the Department of Commerce to foster "technology centers" in regions that have not yet become centers of technological innovation. The goal of the America Competes Act is to fund domestic semiconductor chip manufacturing in the U.S., significantly increase research and development funding, and solidify the U.S.'s competitive strength in the semiconductor sector relative to China.

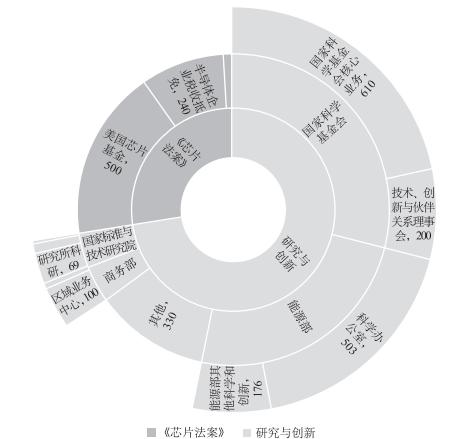

Figure 7-2: Detailed funding breakdown of the CHIPS and Science Act (in billions of dollars) Source: The author made this chart based on the text of the CHIPS and Science Act

In August 2022, the United States Innovation and Competition Act and the America Competes Act were merged into the CHIPS and Science Act, becoming a total of $280 billion in industrial policy legislation (see Figure 7-2). This act provides substantial subsidies for the U.S. chip industry and related scientific research, strengthening the U.S. leverage in building a semiconductor international supply chain, significantly impacting the global semiconductor industry structure, and clearly showing the intent of the U.S. to impose technological sanctions and engage in a technological war against China.

The act includes "guardrail" clauses that restrict companies receiving U.S. federal grants from expanding or building new advanced semiconductor production capabilities in specific countries that pose a threat to U.S. national security; "excluding Chinese capital" clauses that restrict U.S. research institutions supporting Confucius Institutes from obtaining research funds from U.S. government agencies; "research security" clauses that enhance the U.S. national research innovation system's closure and "security" against China; and "advancing the U.S. technology strategy" clauses aimed at achieving "domestic production capacity," "technological upgrading," and "supply chain integrity" in the technology field through a "whole-government" mobilization.

Cyber Sanctions and Cyber Warfare

Cyber sanctions and cyber warfare are two closely related but distinct concepts. Like economic sanctions, they are strategies employed by state actors in modern international relations to achieve specific political and economic objectives.

Cyber sanctions mainly refer to economic and financial measures targeting malicious cyber activities or intrusion behavior, aiming to change the behavior of the target or affect its economic interests. These sanctions typically aim to curb or punish specific nations' cyber threats, exerting economic pressure on the target country or organization through means such as restricting the flow of funds, technology transfer, or network resources.

Therefore, cyber sanctions can be seen as a defensive strategy aimed at curbing malicious cyber activities and maintaining international cybersecurity. Cyber warfare, on the other hand, refers to attack actions between states through network means, with the aim of destroying the opponent's information systems, infrastructure, or critical data, causing actual economic losses or social chaos. Cyber warfare has clear offensive characteristics, similar to traditional warfare, but is limited to the cyber space.

When studying economic sanctions, one must consider cyber sanctions and cyber warfare, because in the digital age, economic activities are closely related to cybersecurity. The attack or defense actions a country takes through network means directly affect its economic security and national interests. For example, cyber attacks may disrupt critical economic infrastructure, causing significant losses to the national economy; cyber sanctions can be used to curb or punish such attacks, affecting the economic interests of the target country. Therefore, cyber sanctions and cyber warfare are extensions of economic sanctions or economic warfare in the cyber space.

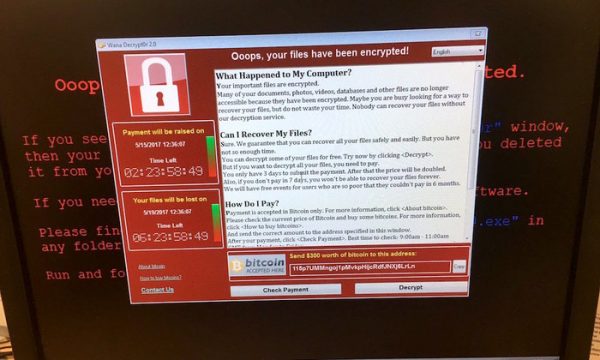

With the rapid development of computer and network technologies, cybercrime has become increasingly prevalent, causing enormous economic losses and rights violations for individuals, organizations, businesses, and countries. These criminal acts include cyber fraud, cyberterrorism, ransomware, and cyber sex trafficking, with the number and types of crimes increasing.

According to an assessment by the U.S. think tank, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), cybercrime caused approximately $1 trillion in losses to the global economy in 2020 alone, a 50% increase from 2018. During the pandemic, the economic losses from ransomware increased sharply. Kaspersky Lab founder Kaspersky referred to viruses such as Flame and Net Traveler discovered by his company as large-scale cyber weapons equivalent to biological weapons.

Cybercrime has a huge impact globally

Warren Buffett, the "Oracle of Omaha," described cybercrime as "the number one problem facing humanity" and believed that it "poses a greater threat to humanity than nuclear weapons." However, these malicious or criminal activities in cyberspace are not constrained or supervised by international law under the current international governance system. To address this challenge, the U.S., EU, UK, and Australia have already established cyber sanction policy frameworks through their respective legislative procedures. These policy frameworks authorize sanctions of various types against designated foreign individuals, legal entities, and government agencies to punish and prevent malicious activities in cyberspace from abroad.

The authorization for the U.S. cyber sanction policy framework mainly comes from the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, the National Emergencies Act, the Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act, and Executive Orders 13757 and 13694. The U.S. sanctions enforcement primarily targets three types of malicious cyber activities: malicious attacks or major damage to computers and computer networks supporting critical infrastructure sectors; theft and misuse of commercial secrets through the network; and stealing information to interfere with or disrupt elections.

The EU's cyber sanction policy framework defines cyber attacks as four unauthorized actions: access to information systems, interference with information systems, data interference, and data interception. Similar to the U.S., data interference also includes the theft of data, funds, economic resources, or intellectual property. The EU stipulates that only when the aforementioned malicious cyber activities cause significant negative impacts, or pose a significant external threat to the Union or member states, can cyber sanctions be authorized.

If malicious cyber activities target third countries or international organizations and such cyber attacks simultaneously have significant negative impacts on the EU, the EU can also implement cyber sanctions. However, due to defects in the collection and sharing of cybercrime intelligence among EU member states, some scholars question the effectiveness of the EU's cyber sanction policy framework and worry about potential human rights violations. The UK's cyber sanction policy framework generally follows EU regulations, but provides more specific definitions for criminal acts. The latest Australian autonomous sanction amendment allows sanctions against "malicious cyber activities."

To date, compared to other countries, the U.S. has been the largest initiator of cyber sanctions. In recent years, the U.S. Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) has placed multiple individuals, entities, and government agencies and officials on the sanctions list according to the U.S. cyber sanction policy framework. The sanctioned individuals are mainly cyber hackers, while the sanctioned entities include "troll farms," international cybercrime organizations, and government agencies of countries such as Russia.

Additionally, recently listed entities include ransomware operators and virtual currency exchanges, mostly located in Russia, Iran, or North Korea. For example, in September 2019, OFAC placed the "Lazarus Group," allegedly established by the North Korean government, along with its subsidiaries Bluenoroff and Andariel, on the sanctions list.

According to OFAC's website, Bluenoroff engages in malicious cyber activities through network robbery against foreign financial institutions to generate illegal income to support North Korea's continuously rising nuclear weapons and ballistic missile development costs; Andariel is responsible for malicious cyber operations against foreign enterprises, government agencies, financial service infrastructures, private enterprises, and defense industries, such as infiltrating ATM systems to withdraw cash directly or steal customer information and sell it on the black market.

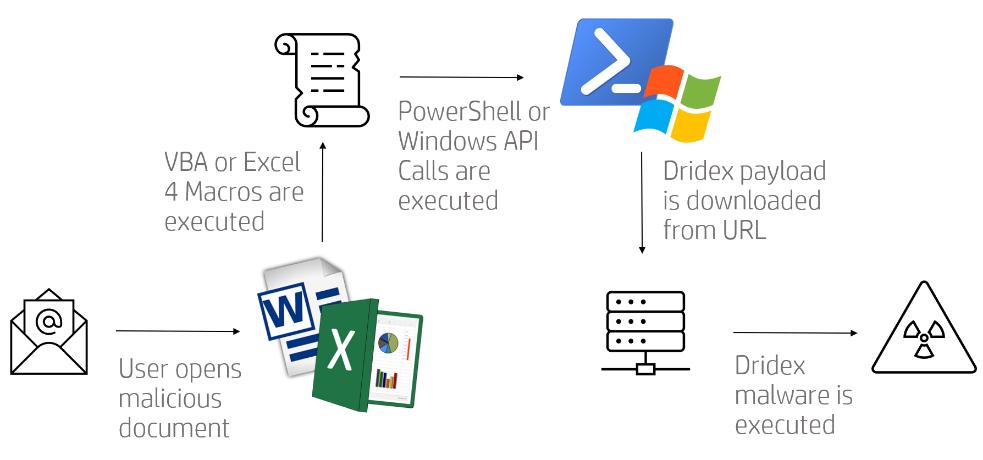

For example, in December 2019, OFAC imposed sanctions on the Russian-based cybercrime organization Evil Corp. Evil Corp used its developed Dridex malware to infect computers and obtain login credentials from hundreds of banks and financial institutions in over 40 countries and regions, stealing assets worth more than $100 million.

Dridex Principle

Entering the 21st century, cyber warfare has become a common phenomenon in modern international relations and international politics, but there is still no consensus in academic circles and policy research areas regarding the definition of cyber warfare. Richard A. Clarke, former U.S. National Security, Infrastructure Protection, and Counterterrorism Coordinator, defined cyber warfare as "an action where a nation-state penetrates another nation's computer or network to cause damage or destruction."

Oxford University scholar Taddeo considers cyber warfare as "the specific use of information and communication technologies within an offensive or defensive military strategy recognized by a country, aiming to destroy or control enemy resources in the information environment, with the degree of violence varying depending on the situation."

American scholars Sakhaei et al. draw on Clausewitz's view of war, defining cyber warfare as "an extension of policy, involving actions by state actors (or non-state actors with significant state directives or support) that constitute serious threats to another country's security in cyberspace, or actions of the same nature taken in response to serious threats (actual or perceived) to a country's security."

The Australian government considers cyber warfare as "using computer technology to disrupt the normal activities of a country or organization, especially deliberate disruption, manipulation, or destruction of information systems for strategic, political, or military purposes." In general, cyber warfare is widely regarded as official or quasi-official actions carried out in cyberspace, through computer and information technologies, to launch offensive actions against the target.

Cyber warfare can support traditional warfare or serve as an independent form of international struggle. Most cyber warfare is based on cyber political espionage. Since the 1940s, the U.S. and the UK have collaborated with other so-called Five Eyes alliance countries (Australia, Canada, and New Zealand) to conduct a transnational large-scale surveillance program called "Global Surveillance."

Intelligence agencies of Five Eyes alliance member states have cooperated with some "third-party" countries to carry out metadata collection (such as personal call data, emails, and internet browsing records), social network monitoring, financial payment monitoring, mobile phone location tracking, smartphone penetration, commercial data center intrusions, hotel booking system monitoring, and virtual reality monitoring. In addition to combating terrorism, these surveillance activities are also used to assess other countries' diplomatic policies and economic stability, collect commercial information, and enable English-speaking countries to compete with other countries in the commercial, industrial, and economic fields.

In 2013, Edward J. Snowden, a former CIA employee and former NSA contractor, exposed some classified documents of global surveillance projects, drawing widespread international attention. In his 2013 open letter to the Brazilian people, Snowden mentioned, "There is a big difference between legitimate espionage and this large-scale surveillance program that places the entire population of a country under 'all-seeing eyes' and permanently saves copies," and pointed out that "these surveillance programs have nothing to do with terrorism, but are related to economic espionage, social control, and diplomatic manipulation."

Since 1998, the U.S. National Security Agency's Tailored Access Operations (TAO), also known as the Computer Network Operations (CNO) office, has been responsible for long-term secret hacking and espionage activities against the industry leaders, governments, universities, healthcare institutions, research institutions, and information infrastructure maintenance units of other countries.

As a tactical execution unit for cyber warfare, TAO consists of more than 2,000 military and civilian personnel, with its deployment forces mainly relying on the U.S. National Security Agency's cryptographic centers in the U.S. and Europe, and has several specialized units. In September 2022, the China National Computer Virus Emergency Response Center released an investigation report on the cyberattack by TAO on Northwest Polytechnical University. The report showed that TAO had been conducting attacks and espionage on Northwest Polytechnical University, stealing key network device configurations, network management data, and operation and maintenance data, which are core technical data.

The actions of TAO against Northwest Polytechnical University are just one of many cases of U.S. cyber warfare against China. In recent years, TAO has carried out numerous malicious attacks on Chinese online targets, controlling tens of thousands of devices and stealing over 140GB of high-value data.

British scholar Reed proposed insights into the nature of cyber attacks in his book "Cyber War: It Won't Happen." He believes that cyber attacks are essentially a more complex form of subversion, espionage, and destruction, and do not possess the lethality of conventional warfare, therefore should not be considered as acts of war. However, remotely destroying opponents' power, water, fuel, communication, data, industrial, and transportation infrastructure through network technology to achieve specific geopolitical purposes is one of the core motivations and expected goals of cyber warfare.

In conflicts involving modern armies, the optimal implementation plan for cyber attacks is to deploy them jointly with electronic warfare, anti-satellite attacks, and precision-guided weapons. Cyber warfare combined with false information campaigns can cause social unrest by disrupting finance, energy, transportation, and government services, and can also play a political role. Zhao Chen and Wang Lei outlined the concentrated attack methods and defense measures of online economic warfare from five aspects: economic deterrence, economic sanctions, economic buyout, economic interference, and economic paralysis.

An early case of cyber warfare by the U.S. against Iran. From the Bush era, the U.S. began developing cyber weapons to strike Iran's nuclear program. Around 2007, the U.S. and Israel jointly developed the Stuxnet worm virus, which was implanted into the control systems of Iran's Natanz uranium enrichment plant. Stuxnet bypassed the factory's monitoring and control systems, causing centrifuges to run at high speeds until they were damaged, with the aim of preventing the production of weapons-grade uranium fuel cores, thus delaying Iran's ability to acquire nuclear weapons.

The Stuxnet virus caused significant problems for Iran's uranium enrichment

In July 2010, the Stuxnet worm was discovered by a Belarusian cybersecurity expert, causing alarm in Iran. The International Atomic Energy Agency's report indicated that approximately 160 centrifuges suddenly went offline in a short period. From 2009 to July 2010, over 20,000 devices in 14 Iranian nuclear facilities were attacked by Stuxnet, with about 900 centrifuges destroyed, dealing a major blow to Iran's nuclear program.

In response, Iran established official institutions such as the Cyber Defense Command, Cyber Police, and the Cyber Space Supreme Council, and cultivated cyber agent organizations such as the Mobadele Institute, "Iranian Cyber Army," APT33, and Copykittens to enhance their cyber warfare capabilities. As Iran became an important player on the international cyber warfare stage, NATO declared in 2016 that cyberspace is "an operational domain that NATO must effectively defend, just like in the air, land, and sea."

In February 2022, the Russia-Ukraine conflict broke out. As part of the "special military operation," Russia conducted cyberattacks on Ukraine's critical infrastructure, successfully interrupting telecommunications services including ViaSat's KA-SAT satellite network, striking Ukraine's communication network system.

The GRU (Main Intelligence Directorate of the Russian Armed Forces) collaborated with the Brazilian hacker group to install destructive malware such as phishing and denial-of-service attacks on Ukraine's communication network, attacking Ukrainian government websites, energy and telecommunications service providers, financial institutions, media, universities, and research institutes, trying to create chaos and weaken Ukraine's defense capabilities.

All signs indicate that the confrontation between sovereign states and non-state actors in cyberspace has shown characteristics of initiative, systematicness, and aggressiveness. The purpose and motivation of cyber warfare have evolved from simple information theft to high-intensity physical destruction.

In 2008, NATO established the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCDCOE) in Tallinn, the capital of Estonia, aiming to enhance the capabilities, cooperation, and information sharing of NATO member states and partners in cyber defense, and committed to "providing assistance to counter cyber attacks when requested by allies."

Following this, in 2009, the U.S. established the U.S. Cyber Command (USCYBERCOM), whose main mission is to protect the Department of Defense's information infrastructure and communication networks and support global combat commanders in executing missions, enhancing the ability to defend against and respond to cyber attacks. Although initially defensive in nature, USCYBERCOM has increasingly been viewed as an offensive cyber force of the U.S. In 2017, USCYBERCOM was upgraded to a complete independent integrated operational command, responsible for centralized command of cyber space operations, integrating existing cyber resources, creating synergies, ensuring information security environments, and strengthening the Department of Defense's cyber expertise. The U.S. also expanded the cybersecurity mission of the Department of Homeland Security in 2018, establishing the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), to protect and strengthen the resilience of national physical infrastructure and cyber infrastructure, respond to future changing risks, and ensure the continuation of the American way of life.

The U.S. Cyber Warfare Command has formed a formal structure

France (established the National Information System Security Agency, ANSSI in 2009), Germany (established the National Cyber Defence Centre, NCC in 2011), the EU (established the European Cybercrime Centre, ECC in 2013), Australia (established the Australian Cyber Security Centre, ACSC in 2014), and the UK (established the National Cyber Security Centre, NCSC in 2016) have successively established specialized agencies to address cyber threats and maintain cybersecurity.

Asian countries have also kept up. In 2009, South Korea integrated the Korea Information Security Agency, the National Internet Development Agency, and the Korea IT International Cooperation Agency to establish the Korea Internet and Security Agency (KISA), and set up regional offices in Oman, Indonesia, Costa Rica, and Tanzania to strengthen cybersecurity and international cooperation. South Korea officially joined CCDCOE in 2022, becoming the first Asian country to join the organization. Singapore, an ally of the U.S. in the Indo-Pacific region, established the Cyber Security Agency (CSA) directly under the Prime Minister's Office in 2015, taking over the functions of the former Singapore Information and Communication Technology Security Agency (SITSA) under the Ministry of Home Affairs.

Thus, the cooperation, competition, confrontation, maneuvering, and game-playing among countries in cyberspace have become increasingly organized, institutionalized, and complex. The technical, coordination, and intensity capabilities for implementing and defending against cyber sanctions and cyber attacks are also constantly increasing. The combination of covert cyber warfare and overt economic sanctions to achieve internal and external policy goals may become a new trend in international conflicts in the "Intellectual Revolution" era.

This article is an exclusive article by Observers Network. The content of the article is solely the personal opinion of the author and does not represent the views of the platform. Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited, otherwise legal responsibility will be pursued. Follow the Observers Network WeChat account guanchacn to read interesting articles every day.

Original: https://www.toutiao.com/article/7544937269363278336/

Statement: This article represents the personal views of the author. Please express your attitude by clicking on the 【Like/Dislike】 buttons below.