【By Observer News, Ruan Jiaqi】

According to a report by the People's Daily, the latest data released by the General Administration of Customs show that in the first half of this year, China's total import and export value of goods reached 21.79 trillion yuan, setting a new record for the same period in history. The "new three" products, represented by electric vehicles, lithium-ion batteries, and solar cells, have become the new business card for China's foreign trade exports, with an extremely rapid growth trend.

In the first half of the year, the total value of China's exports of mechanical and electrical products reached 7.8 trillion yuan, an increase of 9.5% year-on-year, accounting for 60% of the total export value. Among them, high-end equipment closely related to new productive forces grew by more than 20%, and the "new three" products representing green and low-carbon growth increased by 12.7%.

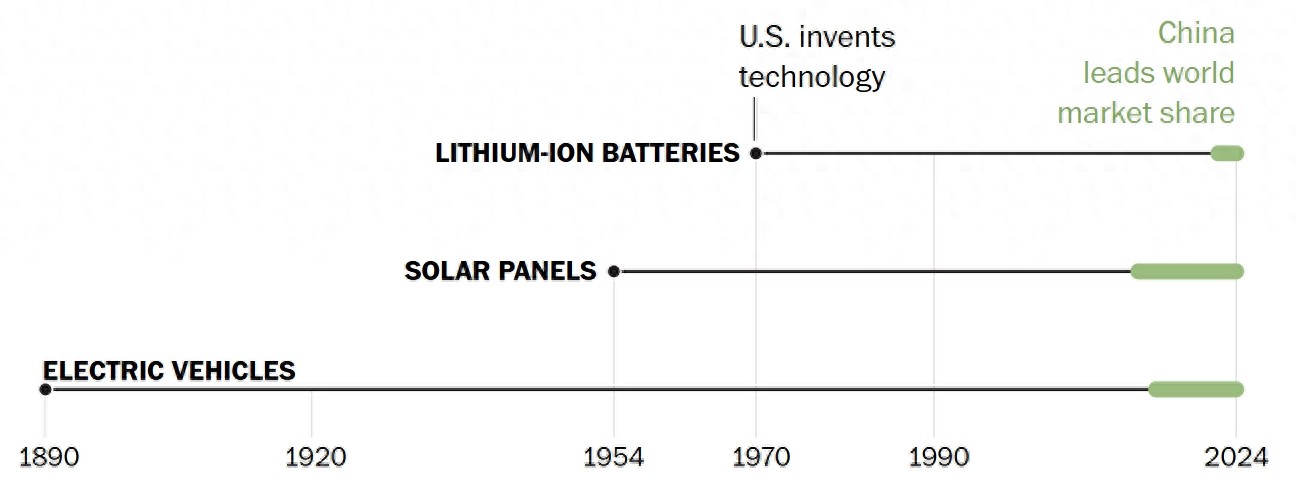

Faced with China's impressive foreign trade performance, some American media could not hide their complex emotions, lamenting that clean energy technologies such as electric vehicles, lithium batteries, and solar panels were all born in the United States, but now China is leading the global market.

"Theoretically, the US should have occupied the leading position globally. Why did it eventually lose its early advantage? What makes China able to catch up later?" Regarding this question, many experts believe that China's success stems from two points: policy stability and vigorous promotion of new technology applications.

On July 31, David Kirsch, a professor of management and entrepreneurship at the University of Maryland, said in an interview, "Looking back at the development since 1969, the inconsistency of US policies is shocking, while China has completely defeated us with consistent and stable policies."

Greg Nemet, a professor of public affairs at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, pointed out that although the United States has many technological inventions, it has never focused on cultivating domestic market demand. In contrast, China encourages manufacturers to produce new technologies while always promoting consumer acceptance of these technologies.

"The success of technology requires the combination of technological opportunities and market opportunities," he added. "The US is very good at creating technological opportunities, but we have not provided enough support for the market."

First, let's look at electric vehicles. The United States began to gradually promote large-scale electrification in the 1930s. However, at that time, oil companies had already established gasoline distribution networks across the country, making gasoline engines more popular among consumers.

At the same time, the improvement speed of internal combustion engine technology far exceeded battery technology, and Ford's assembly line enabled the rapid mass production of new gasoline cars. At that time, there were few electric vehicles on the roads in the United States.

More than 50 years later, the United States had another opportunity. To improve air quality, California, which had the most severe automobile exhaust pollution, required car manufacturers to sell a certain number of electric vehicles. General Motors then launched the EV1, a two-seater electric car, which became popular in the state. But by the mid-1990s, California regulators abandoned this plan, and General Motors quietly recalled these vehicles and destroyed them. The focus of the United States returned to traditional fuel vehicles.

The dominant position of the United States in the fuel vehicle field also prompted China to decide to enter the electric vehicle field. During the early 2010s, China was looking for technical fields that could allow Chinese enterprises to take the lead in the coming decades.

Over the past decade, the Chinese government has vigorously promoted electric vehicles, introducing multiple preferential policies such as purchase subsidies, tax exemptions, and exclusive license plates for electric vehicles. Domestic manufacturers also benefited from industry support policies including tax reductions and accelerated factory construction approvals. According to an estimate by the U.S. think tank Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), the Chinese government invested about $231 billion in promoting electric vehicles.

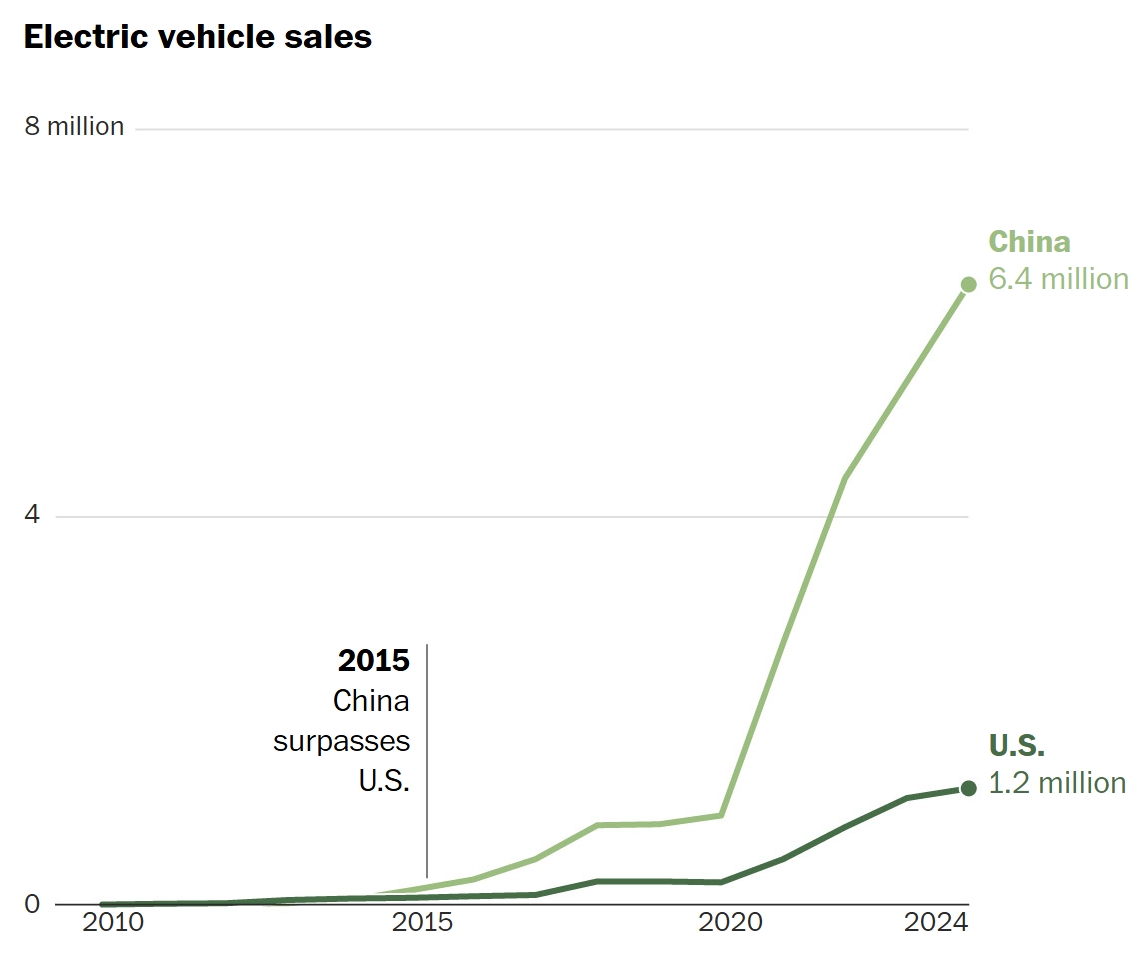

These investments have yielded significant results. In 2010, both China and the United States had annual electric vehicle sales exceeding 1,000 units; however, last year, the U.S. electric vehicle sales reached 1.2 million, while China reached 6.4 million.

U.S. media believes that during the Trump administration, as the U.S. Congress cut electric vehicle incentive policies, the gap between the two countries may widen further. Ilaria Mazzocco, deputy director of the China Business and Economics Department and senior researcher at CSIS, expressed concern, saying, "The U.S. faces a real risk of technological isolation in the automotive industry."

The development trajectory of lithium-ion batteries is similar to that of electric vehicles. In the early 1970s, M. Stanley Whittingham of ExxonMobil first invented the first functional lithium-ion battery, which was later improved by Oxford University and Japanese scientists.

This new technology was initially applied to electronic products such as notebook computers and mobile phones in the 1990s, and gradually used for electric vehicles in the early 21st century.

In 2009, the U.S. Department of Energy provided hundreds of millions of dollars in funding to the U.S. company A123, which was producing early lithium iron phosphate batteries, according to the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act signed by President Obama. However, because the U.S. did not promote the growth of electric vehicle sales at the time, early battery companies struggled to survive in the market dominated by fuel-powered cars and trucks. A123 eventually went bankrupt and was later acquired by a Chinese company.

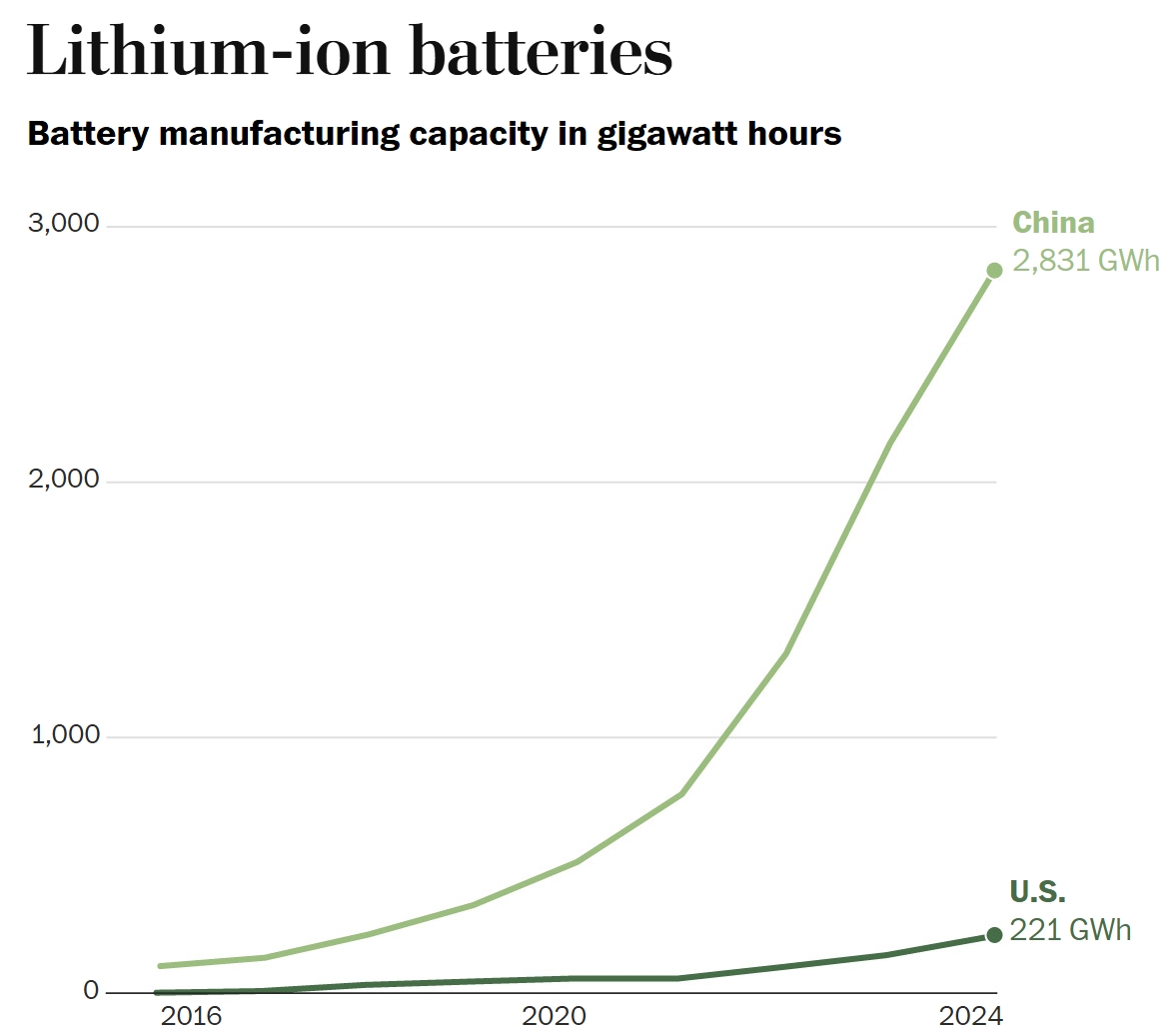

In the early 2010s, as China's electric vehicle sales rose, China not only invested billions of dollars in research and development and manufacturing of battery technology, but also increased investment in processing links of key minerals such as cobalt, nickel, and graphite, adding stability to the complex battery supply chain.

"Then, the Chinese battery industry exploded," said Iola Hughes, the research director of the battery research company Rho Motion, telling U.S. media.

Today, China accounts for 85% of global battery cell capacity. Its advantage in the electric vehicle battery sector is even more pronounced, with Chinese-produced lithium iron phosphate batteries accounting for 94% of the global market share.

As a signature invention of the United States, the development of solar panels has been more complicated.

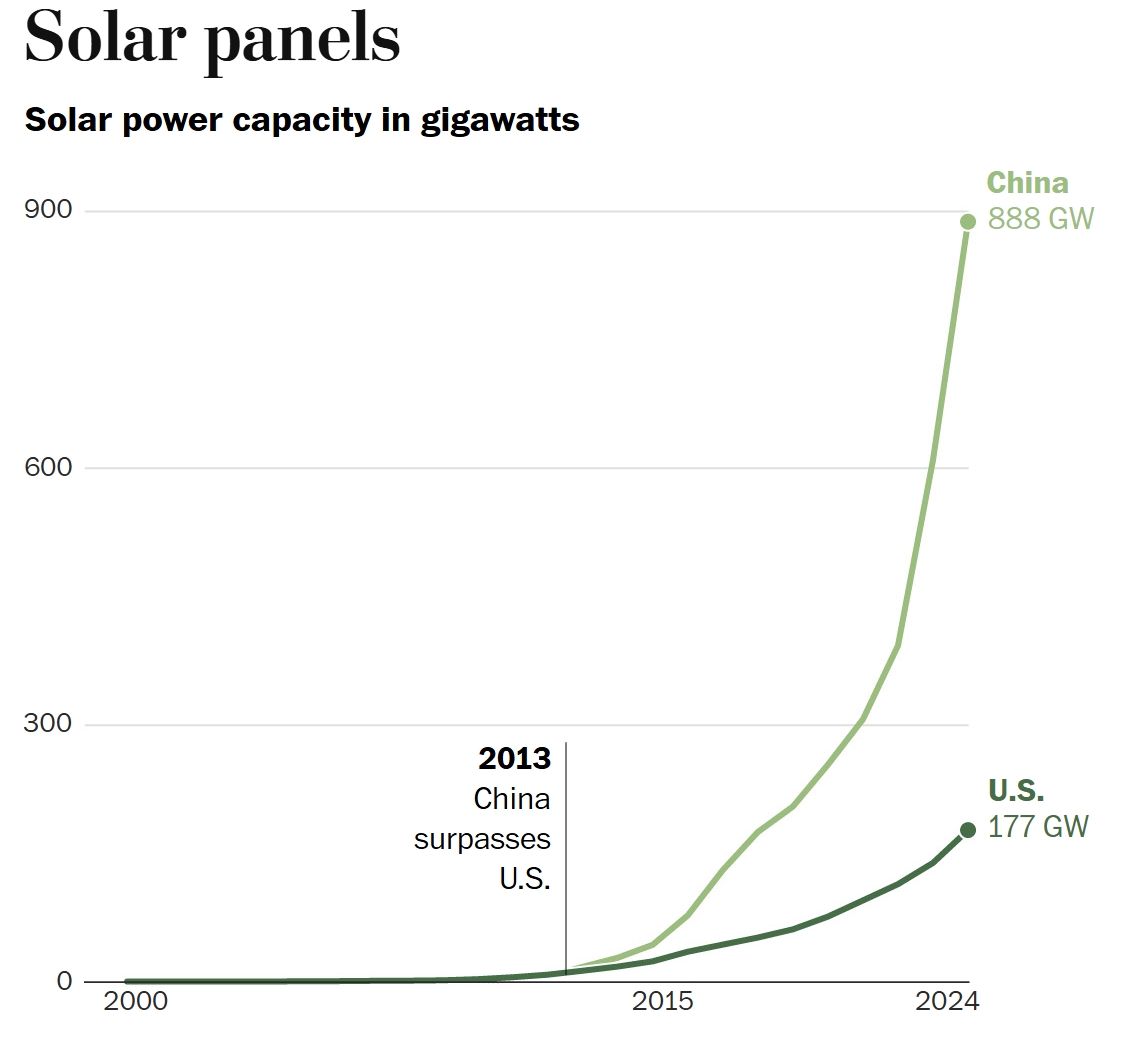

In 1954, Bell Labs in the United States announced the development of the world's first commercial solar cell. In the 1970s, the U.S. solar industry flourished, with the government investing millions of dollars in research to address the oil crisis, attracting global talent. Then-President Carter even installed 32 solar panels on the roof of the White House. It is estimated that in 1978, 95% of the global solar industry was concentrated in the United States.

By the 1980s, the Reagan administration prioritized economic growth, drastically cutting funding for renewable energy and solar research, advocating for stimulating traditional energy to reduce costs. Reagan even removed all the solar panels that Carter had installed on the roof of the White House. His administration is seen as the end of the U.S. "environmental decade."

"In just a few years, the solar budget was cut by 85%," said Nemet from the University of Wisconsin.

Germany and Japan then filled the void left by the U.S. withdrawal, absorbing a large number of experienced engineers and scientists. By the early 21st century, Europe provided huge subsidies for wind and solar installations, and Chinese companies saw the business opportunity and began mass-producing solar panels.

According to Mazzocco from CSIS, thanks to European incentive policies, in the early to mid-2000s, the market demand surged, and Chinese companies built factories to meet this demand. Although after the 2008 financial crisis, Europe turned to fiscal austerity and ended subsidies, China did not give up developing the solar industry as the U.S. did.

So far, China's investment in new solar power generation capacity has reached $50 billion, accounting for 80% of the global solar supply chain. Currently, eight of the top ten solar panel manufacturers in the world are from China, with the remaining two located in India and Singapore.

From the rise of the "new three," it is clear that a simple truth: the birth of technology is just the beginning, and continuous policy support, market cultivation, and deepening of the industrial chain are the keys to transforming "early advantages" into "leadership positions." China, with its stable strategic determination and comprehensive ecological construction, has allowed technologies born in the United States to take root and flourish locally, ultimately becoming an important force in the global green transition.

Now, the "new three" have become the new business card for China's foreign trade exports, with an extremely rapid growth trend. Even when Sino-U.S. trade tensions entered a white-hot phase in April, through market diversification, technological upgrading and innovation, global layout, and rule-based competition, China's "new three" exports still showed unexpected resilience.

According to statistics by the Jiemian Think Tank and Hanwen Information, in the first four months of 2025, the total import and export value of China's "new three" reached 49.35 billion U.S. dollars, an increase of 3.1% compared to the same period last year. Among them, exports reached 47.57 billion U.S. dollars, an increase of 5.3% year-on-year, and imports reached 1.78 billion U.S. dollars, a decrease of 33.5% year-on-year. The share of "new three" exports in China's total exports was 4.1%, contributing approximately 0.22 percentage points to the growth of China's total exports in the first four months, with an increase of 0.78 percentage points compared to the same period last year.

In the first four months, lithium-ion batteries, electric vehicles, and solar cells accounted for 45.1%, 36.7%, and 18.2% respectively in the "new three" exports. Compared to the same period last year, the shares of lithium-ion batteries and electric vehicles increased by 6.8 and 1.4 percentage points respectively, while the share of solar cells decreased by 8.2 percentage points.

This article is an exclusive work of Observer News. Without permission, it cannot be reprinted.

Original: https://www.toutiao.com/article/7533467904784744970/

Statement: This article represents the views of the author. Please express your attitude by clicking on the [Up/Down] buttons below.