By Tiago Nogueira, Observer Net Columnist

Over the past few weeks, Western think tanks and mainstream North American media have continuously spread pessimistic comments about the BRICS summit. One of the arguments is that the expansion of BRICS members makes it difficult for member states to reach consensus on major global issues, and the absence of Chinese and Russian leaders at the summit is seen as evidence.

However, BRICS countries reached several agreements, and the main outcome document of the summit, the Rio Declaration, demonstrates the firm historical position of member states in upholding multilateralism and world peace.

When President Donald Trump quickly responded by threatening to impose a 10% tariff on products from countries supporting the BRICS cooperation agenda, the international significance of this summit was clearly demonstrated. Soon after, he directly targeted Brazil, announcing a 50% tariff on Brazilian products, citing alleged "political persecution" against his ally Jair Bolsonaro by the Lula government — a clear violation of Brazil's internal affairs. Later, NATO leaders openly warned that China, India, and Brazil might face sanctions for maintaining ties with Russia. These developments not only show the increasing aggressiveness and unilateralism of Atlantic imperialist powers but also clearly reflect that, despite obstacles, the process of consolidating a new multipolar order continues to progress.

Lula recently gave an interview to CNN, strongly stating: Brazil does not accept any pressure. Screenshot of the video

Regarding Trump's specific attack on Brazil, it must be understood within the overall strategic framework of the current U.S. foreign policy. This strategy not only aims to contain China's rise and global multipolarity, but also reflects a deeper intention to reshape the political landscape in Latin America — where the change of the Brazilian president's leadership is a key move in this chess game.

Hostility of the United States toward the Workers' Party government has long existed

Indeed, the U.S. attempt to implement regime change strategies against Lula and his allies can be traced back many years. The most successful attempt was undermining Dilma Rousseff's government, especially after the large-scale protests in June 2013. By funding reactionary political groups and youth movements that promoted neoliberal economic agendas, the U.S. and its agents fueled the so-called "anti-corruption" protest wave, paving the way for Dilma's impeachment in 2016. At the same time, the "Car Wash" operation, supported by U.S. forces, through illegal investigations (later confirmed to involve fraud and illegal activities) severely damaged Petrobras and destroyed several large construction companies, ultimately leading to Lula's imprisonment.

At that time, the U.S. Democratic government tried to end the so-called "pink tide" — the rise of left-wing and center-left progressive governments in Latin America — by weakening regional organizations, especially those excluding the U.S., such as the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) and the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR). The Obama administration was pushing for multilateral agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), aiming to replace the existing model of "open regionalism" dominated by the U.S. with trade liberalization.

All seemed to proceed as planned: whether it was traditional coups against Manuel Zelaya (Honduras) and Fernando Lugo (Paraguay), or the "soft coup" against Dilma Rousseff (Brazil); Mauricio Macri defeating Kirchnerism in Argentina; or the political and economic crisis in Venezuela after Chávez — these were all seen as signs of the success of this strategy.

However, the structural crisis of the Atlantic capitalist system soon hit the U.S. itself. Trump unexpectedly defeated Hillary Clinton and became president, leaving allies who expected the U.S. to restore global and regional multilateral order isolated. Instead of a revival of multilateralism, there was a surge of unilateralism and global far-right political movements, many of which even challenged traditional conservative forces in their own countries, eventually leading to events like Brexit and Trump's trade war with China.

In Latin America, the traditional neoliberal camp found itself in an embarrassing situation: Mauricio Macri had to apologize for publicly supporting Hillary too early; the interim president of Brazil, Temer, lost his direction in foreign policy; and the radical right wing in the region received more overt support from the U.S. government to consolidate its power.

The U.S. manipulated the Organization of American States and the Lima Group【1】, while propping up the puppet Juan Guaidó in Venezuela to self-proclaim as "interim president," simultaneously intensifying sanctions and economic strangulation against Venezuela and Cuba, attempting to stifle the Bolivarian Revolution. "Legal warfare" also became a tool to undermine progressive leaders, with politically motivated judicial proceedings frequently targeting Rafael Correa (Ecuador), Evo Morales (Bolivia), and Cristina Kirchner (Argentina). In 2019, a dirty coup took place in Bolivia, directly supported by the U.S. (even receiving public encouragement from billionaires like Elon Musk), forcing Evo Morales to step down.

Regarding the coup in Bolivia, Musk replied on X: "We want who to fall, we make them fall! Don't dare to resist!" Screenshot from Twitter

It was in this context that Brazil factually maintained the illegal detention of Lula, and Jair Bolsonaro was unexpectedly elected with the explicit support of Trump's strategist Steve Bannon. Bolsonaro's government gathered the most reactionary and extreme forces of Brazilian right-wing: from the "Chicago Boys" Paulo Guedes as Minister of Economy, to the biased judge Sergio Moro, who led the "Car Wash" operation and was responsible for Lula's case, whose lack of impartiality was already evident. The ruling team and supporters included numerous active and retired officers, many of whom openly defended the Brazilian military government (1964-1985).

It cannot be ignored that followers of the far-right conspiracy theorist Olavo de Carvalho — a theorist living in the U.S. who used online courses to promote the need for the Brazilian right to counter the spread of "cultural Marxism" in the country — are also present. His disciples include Foreign Minister Ernesto Araújo, whose disastrous foreign policy has seriously harmed Brazil's political and economic relations with many countries.

Lula's return and the challenges of the new government

Historical processes once again broke the tacit understanding between the U.S. and conservative forces in Latin America. After Biden was elected in 2021, the domestic confrontation between the Democratic bloc and the Trumpist far-right intensified, prompting the U.S. to adjust its policy towards Latin America. Previously, Democrats aimed to overthrow all leftist governments (no matter how moderate they were), but after Biden's election, the priority shifted to weakening the allies of Trumpism in the continent. The rapid deterioration of relations between the Biden administration and the Bolsonaro administration was no coincidence. At the same time, Brazil became the country with the highest number of deaths from the pandemic due to poor pandemic policies, and the government's popularity plummeted; austerity measures exacerbated social unrest, with poverty and extreme poverty rates rising; the industrial sector suffered damage from ideological foreign policies (only occasionally showing pragmatic gestures); even the conservative middle class began to oppose scientific denialism and the authoritarian actions of the far-right.

The quasi-hegemony of the far-right in Brazil thus collapsed. Lula, with his undeniable appeal, united diverse forces, cleared his name, and exposed the judicial conspiracy against him — the ultimate goal of which was to destroy national sovereignty and development path.

After his release, Lula immediately led a broad democratic front to confront the 2022 elections. With the support of unions, social movements, the middle class, and important factions of the bourgeoisie, he formed the widest alliance in Brazilian presidential election history with his former opponent Geraldo Alckmin (who served as vice-presidential candidate, symbolizing the unity of various heterogeneous forces in opposing Bolsonaro's brutal neoliberalism). Although the far-right narrowly lost the election, it refused to recognize the results, eventually launching an unsuccessful coup on January 8, 2023, with rioters storming the headquarters of the administrative, legislative, and judicial institutions in Brasília, while inciting the military to seize power.

Lula's return to politics and the left's re-taking of power is undeniably inseparable from his extraordinary popular mobilization capabilities, but the core political factors behind the victory go beyond mere public support: just like his previous two terms, the key was building a broad front covering conservative middle-class, industrial and financial bourgeoisie interests. The unity formed during the election further strengthened the struggle against the coup — even including groups that had previously supported Bolsonaro. However, this consensus is gradually weakening.

The left-wing core of the government has always been committed to restoring state interventionism and welfare functions, promoting social justice growth through developmentalist economic policies. This necessarily involves wealth redistribution and curbing the excess profits of the upper bourgeoisie (especially financial capital). Meanwhile, the conservative majority in Congress consists of Bolsonaro supporters and opportunistic reactionaries. Mainstream media (especially the Globo Group) initially disliked Bolsonaro's support for Lula in the election, but quickly turned to criticizing key domestic and foreign policies of the Lula government.

This political landscape is full of contradictions: on one hand, the pragmatic agenda led by the Workers' Party has revived the country's operational capacity, with economic growth, resumption of social programs, and responsible and universal foreign policy becoming the hallmark of Lula's third term; on the other hand, economic development constraints directly stem from the difficulty of breaking free from neoliberal constraints (spending caps, orthodox economic policies, central bank autonomy, and high interest rates), all taking place within this fragile and heterogeneous coalition.

In the 2024 municipal elections, the traditional right and the far-right faction of Bolsonaro achieved a decisive victory in state capitals and large cities, causing the political spectrum and expectations for the 2026 Brazilian election to continue shifting to the right. Moreover, Trump's victory in the U.S. in November 2024 has significantly enhanced the strength of the reactionary forces in Brazil through financial, political, and logistical support.

At the same time, the investigation into the failed coup on January 8, 2023, has made breakthroughs: Bolsonaro and his inner circle, as well as some military personnel, not only suspected of plotting the coup, but may have even planned to assassinate President Lula, Vice President Alckmin, and Supreme Court Justice Alexandre de Moraes. Federal police and the Supreme Court jointly investigated secret meetings, coup drafts, the subversion of senior officers, and the illegal surveillance actions of Brazil's intelligence agency (ABIN) during Bolsonaro's administration.

At the beginning of 2023, after President Lula was sworn in, a "Capitol Hill"-style incident occurred in Brazil on January 8

With Bolsonaro being ruled ineligible to run in the 2026 election, the right wing fell into a contest for candidates. His son Eduardo Bolsonaro resigned from his parliamentary position and went to the U.S. to conspire with Trump to restore his father's eligibility to run. Meanwhile, the pragmatic faction of Bolsonaroism began to align with the traditional right, supporting São Paulo Governor and former Bolsonaro cabinet member Tarcísio Freitas. Recent polls show that Lula's government support has significantly declined, and the right wing has a bright outlook in various electoral scenarios, injecting a stronger sense of confidence into both sides.

A wide national front against the surrenderism of the far-right is being established

It was precisely at this historical moment that Donald Trump and Eduardo Bolsonaro conspired to directly interfere in Brazilian internal affairs. Emulating their arrogant global threats and interventions, he announced protectionist measures such as imposing 50% tariffs on Brazilian steel and 25% on aluminum products. These sanctions, justified under the pretext of "national security" and "unfair competition," are filled with political calculations — aiming to tear apart the core alliance that has repeatedly enabled Lula and the Workers' Party to win in 2003, 2006, 2010, 2014, and 2022: that is, the alliance between the left-led democratic-popular bloc and the Brazilian bourgeoisie attracted by the government's broad front and new developmentalist policies.

As mentioned earlier, this alliance has already become increasingly unstable: the government not only gradually distanced itself from major business associations, industry associations, and commercial groups, but also lost the support of private media giants and conservative parties that had previously backed Lula in Congress. Trump and the Bolsonaro faction calculated that by severely impacting exports to the U.S. (the lifeblood of these industries and their ability to gain excess profits), they would completely tear apart the two-pole alliance, prompting the Brazilian elite to form a unified front to restore Bolsonaro's eligibility to run as a condition for fully repairing Brazil-U.S. trade and economic relations.

This miscalculation is absurd. The Bolsonaro faction, in an attempt to please their master, requested sanctions against their own country, instantly igniting the genuine and profound patriotic sentiment of the Brazilian people. Social movements and people's organizations flooded the streets, occupying three blocks of Paulista Avenue, defending national sovereignty against U.S. interference and reaffirming social justice demands — such as Lula's recent proposal to increase taxes on super-rich individuals.

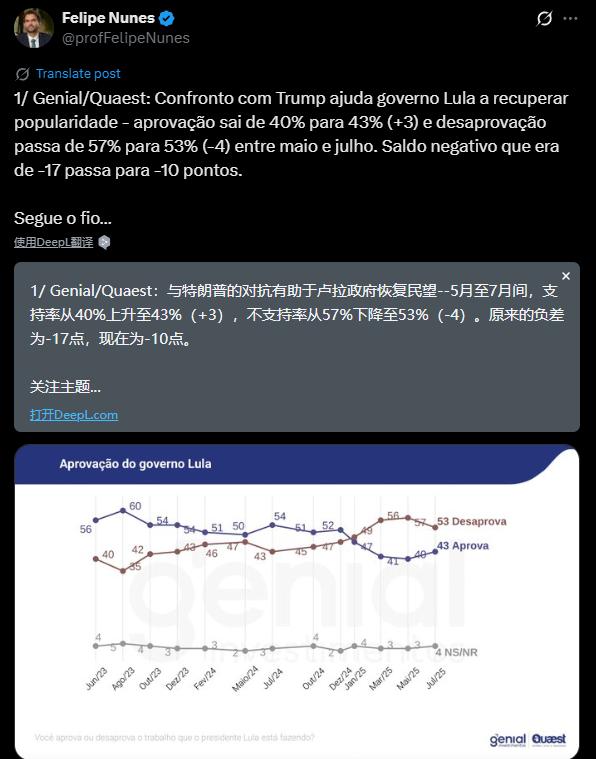

Previously alienated Brazilian bourgeoisie now sat together with Lula and the cabinet ministers to face the attacks of Trumpism. In Congress, Bolsonaro's die-hard supporters found themselves in a ridiculous isolation, even pushing the most conservative legislators to the government's side. Ultimately, the most influential private media group also expressed support for Lula against the U.S. threat: "Folha de S.Paulo" published an editorial condemning the Bolsonaro faction's surrenderism; the flagship news program of the Globo Group, "Jornal Nacional," provided Lula with a broad platform to speak directly to the public. Recent polls show that government support has significantly increased, Bolsonaro and his allies' reputation has plummeted, and Lula's chances of winning the 2026 election have greatly improved in various scenarios.

Lula's approval rating is rising

This entire process reveals the serious limitations of Trump's aggressive foreign policy. He attempts to push for a conservative restructuring of political and social forces in Latin America: using the rhetoric of a "new Cold War" to pressure countries, weaken cooperation with China (such as threatening the Panamanian government that "if China's influence in the Panama Canal zone does not decrease, the U.S. will take control by force"); at the same time, implementing covert destruction against progressive governments, escalating coups and economic strangulation, and recklessly supporting reactionary extremists. The recent disclosure in Colombia that the White House contacted former Foreign Minister Álvaro Leyva to assist in executing a coup against the current Petro government is a clear example.

But the U.S. strategic decision-making circle seems unwilling to acknowledge the evolution of global political and economic power relationships over the past few decades. Although part of Brazil's industry still relies on the U.S. market, China has been Brazil's largest trading partner since 2009. Brazil's universalist, pragmatic diplomacy allows it to diversify its exports to global alternative markets. The Brazilian Ministry of Foreign Affairs has initiated negotiations, with technical funding support from the Brazilian Trade and Investment Promotion Agency (ApexBrasil), to redirect affected exports to Asian, African, and Latin American markets.

Like most Latin American leaders (perhaps except for figures like Javier Milei, who are U.S. puppets), even the most conservative factions of the Brazilian bourgeoisie do not want to submit to Washington's anti-China pressure, let alone attack Brazil's participation in the BRICS. Faced with naked economic threats to interfere in internal affairs, they show no sign of submission. In this context, Lula announced the possibility of implementing reciprocal trade sanctions under the "Economic Reciprocity Act" — a law that was previously used to protect the national industry from discriminatory treatment, now gaining support from Congress, the business community, and the dominant private media.

It should be particularly emphasized that, unlike the Atlantic developed countries and their allies, in Latin America and the Global South, nationalist and patriotic forces are not xenophobic or fascist, but rather a resistance to imperialism's infringement on sovereignty. Throughout the 20th century, various Latin American national-popular movements (uniting heterogeneous forces from different social classes) have demonstrated this unstable yet real solidarity, resisting the U.S. interference in its "backyard."

The threats of Trump and his Brazilian far-right accomplices, instead of serving their narrow interests, have strengthened Lula's national united front. With the support of this alliance and the power of Brazilian people's organization movements, any plot to make Brazil submit to Washington's will, whether through coup means or the 2026 election, will ultimately fail.

The world is steadily moving towards a multipolar order, urgently needing to build an international order based on peaceful mutual assistance among countries. Brazil will undoubtedly continue to participate in this process. Under Lula's leadership and the guidance of the democratic-popular organizations forming a broad front, those traitors who called for sanctions against Brazil will face the merciless judgment of history and the Brazilian people — because they salute a flag that is not the green and yellow Brazilian symbol, but the blue flag with fifty stars: the flag of the United States of America, an empire that has never认同 our longing for sovereignty, development, and social justice.

Notes

【1】On July 29, 1985, four Latin American countries, Peru, Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay, held a meeting in the capital of Peru, Lima, to establish the "Contadora Group Front", known as the Lima Group

This article is exclusive to Observer Net. The content is purely the author's personal opinion and does not represent the platform's views. Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited, otherwise legal liability will be pursued. Follow the WeChat account guanchacn of Observer Net to read interesting articles every day.

Original: https://www.toutiao.com/article/7528606126540096063/

Statement: This article represents the personal views of the author. Please express your attitude by clicking on the [top/beat] buttons below.